A Joint Project of

The Foreign Policy Initiative, American Enterprise Institute, and The Heritage Foundation

“There are some who think the era of U.S. global leadership is over, and that decline is what the future inevitably holds for us. Some even believe that decline offers us a better future, in the model of our relatively pacifist social-democratic allies.

“But this is an error. A weaker, cheaper military will not solve our financial woes. It will, however, make the world a more dangerous place, and it will impoverish our future.”

—The Foreign Policy Initiative’s William Kristol, the American Enterprise Institute’s Arthur C. Brooks, and the Heritage Foundation’s Edwin J. Feulner

in “Peace Does Not Keep Itself,” op-ed, Wall Street Journal, October 4, 2010.

The future of America’s national security hangs in the balance. Facing a looming Thanksgiving deadline, a select bipartisan panel of 12 lawmakers is struggling to hammer out legislation that would reduce the federal deficit by more than $1.2 trillion over the next 10 years. However, it remains unclear if they will succeed.

If this so-called “Super Committee” falls short—or if the required deficit reduction legislation is not enacted by January 15, 2012—then the Pentagon’s long-term budget will suffer the brunt of the consequences. Specifically, it will face not only lowered “sequestration” ceilings on spending that will effectively cut more than $500 billion from what the Pentagon was projected (based on Obama’s fiscal year 2012 budget proposal) to spend over the next ten years, but also “sequestration” cuts that will further indiscriminately slash as much as $500 billion more. In all, sequestration’s spending ceilings and cuts could effectively trim anywhere from $500 billion to over $1 trillion from projected long-term defense spending.

A wide range of America’s civilian and military leaders have voiced grave concerns about the dangers of further defense cuts. Most recently, in letters sent to Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) on November 14, 2011, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta explained that sequestration cuts—which, under current law, “must be applied in equal percentages to each ‘program, project, and activity’”—would be “devastating” to the military. He wrote that, under full sequestration, the United States would have: “[t]he smallest ground forces since 1940”, “a fleet of fewer than 230 ships, the smallest level since 1915”, and “[t]he smallest tactical fighter force in the history of the Air Force”. The Pentagon would face the prospect of terminating the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter; littoral combat ship; all ground combat vehicle and helicopter modernization programs; European missile defense; all unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems. It may also have to delay the next-generation ballistic missile submarine; terminate next-generation bomber efforts; and eliminate the entire intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) leg of America’s nuclear “triad”. Panetta thus concluded:

“Unfortunately, while large cuts are being imposed, the threats to national security would not be reduced. As a result, we would have to formulate a new security strategy that accepted substantial risk of not meeting our defense needs. A sequestration budget is not one that I could recommend.”

As lawmakers, policymakers, and the American public debate how best to achieve federal deficit reduction, this analysis debunks three common myths about U.S. spending on national defense.

MYTH #1: Defense spending is the main driver of America’s growing debt and deficit.

FACT: The main driver of America’s growing debt and deficit is domestic spending—especially entitlement spending—and not defense spending.

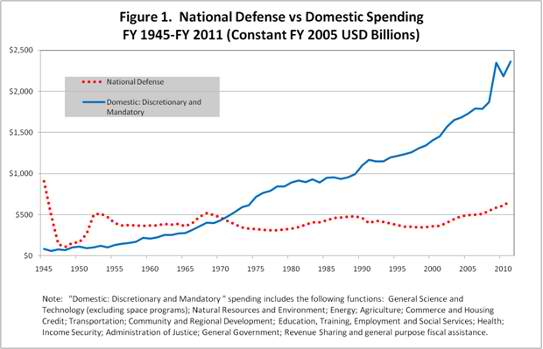

No doubt, U.S. federal spending has dramatically ballooned in recent decades. But as Figure 1 shows, spending on mandatory and discretionary domestic programs—in particular, on entitlements—has experienced almost exponential growth since the 1970s. Contrast that with spending on national defense, which has stayed comparatively stable, even when supplemental

funding for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq is included. Indeed, between 2000 to 2010, the U.S. government spent over $5 trillion more on non-defense programs than what the Congressional Budget Office had originally projected it would spend. If one adjusts for inflation, then that number climbs to approximately $5.6 trillion in constant FY 2012 dollars.

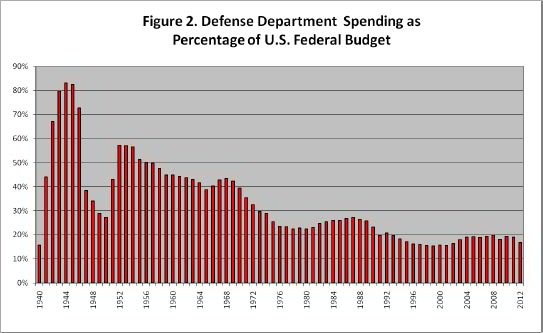

As a result, entitlements today constitute nearly 60% of the $3.5 trillion federal budget. In contrast, total discretionary spending amounts to only 35% of the budget—with roughly half of that going to national defense. As the Director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Douglas Elmendorf, said: "Discretionary spending is a shrinking share of federal outlays over time, and mandatory entitlement spending is a growing share.” Indeed, as Figure 2 illustrates, despite the historical growth of U.S. spending, outlays on the Defense Department as a percentage of the federal budget have declined.

Given the spiraling growth of entitlements, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta—who earlier served as President Clinton’s budget director—has repeated the need to focus on the main driver of America’s debt and deficit. For example, he said on September 20, 2011:

“If you’re serious about dealing with the deficit, don’t go back to the discretionary account [which includes defense spending]. Pay attention to the two-thirds of the federal budget that is in large measure responsible for the size of the debt that we’re dealing with.”

MYTH #2: The Pentagon hasn’t had spending cuts.

FACT: Defense spending has been subjected to several rounds of reductions under President Obama, with long-term cuts amounting to roughly $850 billion. Moreover, if Congress fails to pass into law a massive deficit-reduction bill by January 12, 2012, then long-term defense will be again cut—this time, by as much as $500 billion.

So far, the Obama administration has presided over at least three rounds of defense reductions.

-

Round 1: In 2009, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates not only cancelled 20 major weapons systems, but also delayed or targeted for cancellation other vital replacement systems. Cuts in spending on these programs is leading to the loss of planned military capabilities in the future, as Mackenzie Eaglen of the Heritage Foundation explained:

“Canceled equipment programs include: a combat search-and-rescue helicopter; the F-22 fifth generation fighter; the Army's Future Combat System; the multiple-kill vehicle for missile defense; a long-range bomber for the Air Force; the VH-71 presidential helicopter; the Transformational Satellite (T-Sat) program, and the second Airborne Laser aircraft. In addition, the administration pushed construction of an aircraft carrier out four years to five, reduced the number of Ground-based Midcourse Defense interceptors from 44 to 30, and abandoned the Navy's next-generation cruiser. The recently passed 2011 defense budget was not spared the axe, either. Some of the reductions included: ending production of the country's only wide-bodied cargo aircraft, the C-17; terminating the EPX intelligence aircraft; permanently canceling the Navy's cruiser; ending another satellite program, and killing the Marine's Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle. The Army's surface-to-air missile program and its Non-Line-of-Sight cannon are also gone.”

Summing up this round of cuts, Secretary Gates said: “All told, over the past two years, more than 30 programs were cancelled, capped, or ended that, if pursued to completion, would have cost more than $300 billion.”

-

Round 2: In 2010, then-Secretary of Defense Gates initiated a drive to save $78 billion over a five-year period. As Gates later explained, that drive had four parts:

“First, the approximately $54 billion in DoD-wide overhead reductions and efficiencies… which included a freeze on all government civilian salaries. Second, roughly $14 billion reflecting shifts in economic assumptions and other changes relative to the previous FYDP [five-year defense plan]—for example, decreases in the inflation rate and projected pay raises. Third, $4 billion of savings to the Joint Strike Fighter program to reflect re-pricing and a more realistic production schedule given recent development delays. And fourth, more than $6 billion was saved by our decision to reduce the size of the Active Army and Marine Corps starting in FY 2015.”

-

Round 3: In August of this year, President Obama and Congress struck a grand bargain to raise the U.S. debt limit known as the Budget Control Act of 2011 (Public Law 112-25). This controversial law immediately placed ceilings on discretionary “security” spending—defined to include the Pentagon, as well as the State Department, Homeland Security, Veterans Affairs, the Energy Department’s National Nuclear Security Administration, foreign aid programs, and the U.S. intelligence community.

In implementing the Budget Control Act’s spending ceilings, the White House’s Office of Management and Budget is reportedly looking to trim as much as $489 billion more from the Pentagon’s budget over the next decade. In turn, the effect of this round of cuts is already starting to have an impact on future defense planning. As the Washington Post reported on November 2, 2011: “The military chiefs of staff told Congress … that all four services will have to shrink their forces to meet the planned 10-year cut of $450 billion [or more] in defense spending. Until now, only the Army and the Marines have said they would have to cut troops.”

These three rounds of defense reductions have yielded roughly $850 billion in long-term cuts. During this time period, no other government agency has been asked to implement reductions comparable to these defense cuts.

That said, the Pentagon still faces the threat of yet another round of deep cuts. Under the terms of the Budget Control Act, a bipartisan “Super Committee” of 12 select lawmakers has until November 23, 2011, to finish the difficult task of negotiating a legislative package that would reduce the federal deficit by more than $1.2 trillion in the coming ten years. If the Super Committee misses the mark, or if Congress fails to enact into law such a legislative package before January 12, 2012, then the Budget Control Act’s so-called “trigger” provision will impose deep “sequestration” ceilings and cuts on national defense spending.

The Budget Control Act’s trigger provision targets the Defense Department disproportionately. First, it places even lower long-term ceilings on the so-called “050 budget function”—a spending account for “national defense” programs that encompasses the Pentagon’s base budget, the classified budget for certain specific national security activities, the defense programs of the Energy Department’s National Nuclear Security Administration, and defense-related activities in other agencies. Given that the Defense Department typically consumes 96 percent of this “national defense” spending account, the trigger provision’s caps on “national defense,” by themselves, would effectively cut $574.3 billion from what the Pentagon was projected to spend on its base budget over the next decade.

Second, the trigger provision makes defense spending—already lowered more than half-a-trillion dollars by the new multi-year caps—absorb half of the sequestration cuts to discretionary spending. The size of required sequestration cuts will depend on the size of federal deficit reduction: put simply, the closer that Congress gets to the goal of cutting the long-term deficit by more than $1.2 trillion, the smaller the sequestration cuts become.

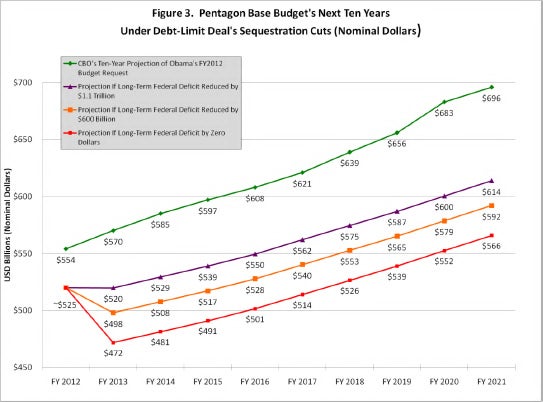

To illustrate the range of possible outcomes under the trigger provision, we assume three different scenarios for sequestration cuts, as illustrated by Figure 3.

- In the first scenario, lawmakers agree to reduce the long-term deficit by $1.1 trillion. Sequestration cuts to the “national defense” account therefore amount roughly to $50 billion, and are subtracted from the trigger provision’s caps on “national defense.” As a result, an estimated $613.7 billion will be effectively cut from what the Pentagon was projected by the Congressional Budget Office to spend on its base budget over the next ten years.

- In the second scenario, lawmakers reduce the long-term deficit by $600 billion. Sequestration cuts to the “national defense” account therefore amount roughly to $300 billion, and are subtracted from the trigger provision’s caps on “national defense.” As a result, an estimated $810.4 billion will be effectively cut from what the Pentagon was projected by the CBO to spend on its base budget over the next ten years.

- In the third scenario, zero long-term deficit reductions are realized—the nightmare outcome for the Super Committee and the Budget Control Act. Sequestration cuts to the “national defense” account therefore amount roughly to $600 billion, and are subtracted from the trigger provision’s caps on “national defense.” As a result, an estimated $1.1 trillion will be effectively cut from what the Pentagon was projected by the CBO to spend on its base budget over the next ten years.

In November 2011 letters to Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta explained why sequestration cuts—which, under current law, “must be applied in equal percentages to each ‘program, project, and activity’”—would have “devastating effects” for the military. Under full sequestration, the United States would have: “[t]he smallest ground forces since 1940”, “a fleet of fewer than 230 ships, the smallest level since 1915”, and “[t]he smallest tactical fighter force in the history of the Air Force”. Reductions to the Defense Department’s civilian personnel would “lead to the smallest civilian work force since DoD became a Department.”

In terms of the Pentagon’s investment accounts—that is, military procurement plus research, development, testing, and evaluation—Panetta added that the Defense Department would face the prospect of terminating: the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter; littoral combat ship; all ground combat vehicle and helicopter modernization programs; European missile defense; all unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems. It may also have to delay the next-generation ballistic missile submarine; terminate next-generation bomber efforts; and eliminate the entire intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) leg of America’s nuclear “triad”. These cuts would stall the military’s modernization at a time when America’s near-peer competitors are rushing to match our current capabilities.

In turn, Panetta said that sequestration cuts would raise dangerous risks and uncertainties to America’s national security. In particular, sequestration:

- “Undermine[s] our ability to meet our national security objectives and require[s] a significant revision to our defense strategy.”

- “Generate[s] significant operational risks; delays response times to crises, conflicts, and disasters; severely limits our ability to be forward deployed and engaged around the world; and assumes unacceptable risk in future combat operations.”

- “Severely reduce[s] force training—[and] threatens overall operational readiness.

In October 2011, the House Armed Services Committee released a study of the impact of defense cuts that reached comparable conclusions.

Amid macroeconomic uncertainty, however, Americans continue to oppose further cuts to the Pentagon. According to a November 2011 Politico-George Washington University Battleground Poll, 82 percent of respondents either strongly opposed or somewhat opposed the Super Committee “cutting spending on defense programs, including programs for soldiers and veterans” to meet its deficit-reduction goal.

The financial impact of deep cuts to the Defense Department will be alarming under any sequestration scenario. More alarming, however, is what more defense cuts could mean for the future of America’s national security and longstanding role in preserving global stability.

Myth #3: Deep cuts in defense spending won’t impact U.S. global leadership.

FACT: In order to maintain global leadership, the United States must make commensurate investments in defense of its national security and international interests.

From the Cold War to the post-9/11 world, U.S. spending on national defense has yielded substantial strategic returns by:

- protecting the security and prosperity of the United States and its allies;

- amplifying America’s diplomatic and economic leadership throughout the globe;

- preventing the outbreak of the world wars that marked the early 20th century; and

- preserving the delicate international order in the face of aggressive, illiberal threats.

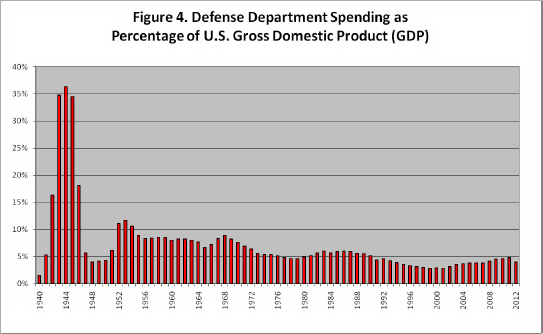

No doubt, the United States has invested non-trivial amounts on national defense to help achieve these strategic objectives. But when viewed in historical perspective, the proportion of America’s annual economic output dedicated to the Defense Department from 1947 to today has been reasonable and acceptable—indeed, a fraction of what it dedicated during World War II. Figure 4 illustrates this. Moreover, in light of the various rounds of recent cuts to the Pentagon’s multi-year budget, defense spending as percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) is on track to reach its lowest point since end of World War II.

Yet defense cuts in recent years have come despite the fact that the United States is facing new threats in the 21st century to its national security and international interests. As Robert Kagan of the Brookings Institution summarized in The Weekly Standard:

The War on Terror: “The terrorists who would like to kill Americans on U.S. soil constantly search for safe havens from which to plan and carry out their attacks. American military actions in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, and elsewhere make it harder for them to strike and are a large part of the reason why for almost a decade there has been no repetition of September 11. To the degree that we limit our ability to deny them safe haven, we increase the chances they will succeed” (emphasis added).

The Asia Pacific: “American forces deployed in East Asia and the Western Pacific have for decades prevented the outbreak of major war, provided stability, and kept open international trading routes, making possible an unprecedented era of growth and prosperity for Asians and Americans alike. Now the United States faces a new challenge and potential threat from a rising China which seeks eventually to push the U.S. military’s area of operations back to Hawaii and exercise hegemony over the world’s most rapidly growing economies. Meanwhile, a nuclear-armed North Korea threatens war with South Korea and fires ballistic missiles over Japan that will someday be capable of reaching the west coast of the United States. Democratic nations in the region, worried that the United States may be losing influence, turn to Washington for reassurance that the U.S. security guarantee remains firm. If the United States cannot provide that assurance because it is cutting back its military capabilities, they will have to choose between accepting Chinese dominance and striking out on their own, possibly by building nuclear weapons” (emphasis added).

The Middle East: “… Iran seeks to build its own nuclear arsenal, supports armed radical Islamic groups in Lebanon and Palestine, and has linked up with anti-American dictatorships in the Western Hemisphere. The prospects of new instability in the region grow every day as a decrepit regime in Egypt clings to power, crushes all moderate opposition, and drives the Muslim Brotherhood into the streets. A nuclear-armed Pakistan seems to be ever on the brink of collapse into anarchy and radicalism. Turkey, once an ally, now seems bent on an increasingly anti-American Islamist course. The prospect of war between Hezbollah and Israel grows, and with it the possibility of war between Israel and Syria and possibly Iran. There, too, nations in the region increasingly look to Washington for reassurance, and if they decide the United States cannot be relied upon they will have to decide whether to succumb to Iranian influence or build their own nuclear weapons to resist it” (emphasis added).

Meeting these threats will require the United States to remain engaged diplomatically and militarily throughout the globe. And that will require continued investment in national defense. However, further cuts to Pentagon spending—especially the “devastating” sequestration cut if the Super Committee effort fails—will fundamentally undermine America’s strategy to defend its national security and international interests. In Secretary Panetta’s words, “we would have to formulate a new security strategy that accepted substantial risk of not meeting our defense needs.”

Conclusion: Defense spending and the price of greatness.

Some today find it tempting to slash investments in America’s national security and international interests, especially given current efforts to reduce the federal debt and deficit. As this analysis has argued, however, defense spending—which has already faced nearly $1 trillion in cuts, arguably more—has done its part for deficit reduction. Moreover, further cuts to defense spending risk fundamentally eroding America’s standing and leadership role in the world.

When Winston Churchill received an honorary degree from Harvard University on September 6, 1943, he remarked:

“The price of greatness is responsibility. If the people of the United States had continued in a mediocre station, struggling with the wilderness, absorbed in their own affairs, and a factor of no consequence in the movement of the world, they might have remained forgotten and undisturbed beyond their protecting oceans: but one cannot rise to be in many ways the leading community in the civilized world without being involved in its problems, without being convulsed by its agonies and inspired by its causes.

“If this has been proved in the past, as it has been, it will become indisputable in the future. The people of the United States cannot escape world responsibility.”

If, as Churchill said, the price of greatness is responsibility, then meeting its global responsibilities will require the United States to sustain commensurate investments in defense of its national security and international interests. It remains to be seen whether Americans will choose to continue answering this calling. But they should.

About Defending Defense

The Defending Defense Project is a joint effort of the Foreign Policy Initiative, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Heritage Foundation to promote a sound understanding of the U.S. defense budget and the resource requirements to sustain America's preeminent military position. To learn more about the effort, contact Robert Zarate ( [email protected] ), Gary Schmitt ( [email protected] ), or Mackenzie Eaglen ( [email protected] ).