This essay series explores Italy’s unique contribution to the rich inheritance of Western civilization, offering a defense of the West’s political and cultural achievements. Find previous installments here, here, and here.

Naples, Italy—At a crisis moment in his life, the epic hero of Virgil’s mythic account of the founding of Rome turns to a woman for counsel. Aeneas, the prince of Troy, had fled the ruins of his city when it fell to the Greeks and arrived in Cumae, west of Naples, anxious and uncertain about his fate. He asks the Sibyl of Cumae, one of the most revered prophets of the ancient world, to guide him in his journey to the underworld. She agrees, but not before delivering a message filled with foreboding:

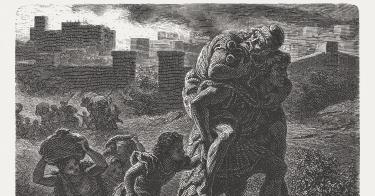

You have braved the terrors of the sea, though worse remain on land—you Trojans will reach Lavinium’s realm—lift that care from your hearts—but you will rue your arrival. Wars, horrendous wars, and the Tiber foaming with tides of blood, I see it all!

The Aeneid has been described by one scholar as “the single most influential literary work of European civilization for the better part of two millennia.” It is a story about origins, written by Rome’s greatest poet when his nation was in the throes of an identity crisis. The Roman people had discarded their republican form of government in favor of an empire run by autocrats. Virgil, probably prompted by the Emperor Augustus, sought to give Rome a revived sense of its civilizing mission in the world—to somehow reconcile the ideals of the republic with the fearsome realities of the empire.

>>> Pliny’s Problem With Christianity—And Ours

The encounter at Cumae marks a turning point for Aeneas. “Come, press on with your journey,” says the Sibyl. “See it through, this duty you’ve undertaken.” Aeneas, obedient to the calling on his life, forges ahead.

America’s founding generation absorbed Virgil (70–19 b.c.) and the lessons of Rome. They admired the story of Aeneas, the man who led a tiny group of intrepid refugees across the sea to create a great nation in a hostile world. Like Rome, the American republic would inaugurate a new social and political order. Indeed, the motto on the Great Seal of the United States, a novus ordo seclorum—a new order for the ages—was borrowed from Virgil’s book of poems, The Eclogues. Unlike Rome, however, this political order would be based on the concepts of human equality and human freedom.

It thus comes as no surprise that the progressive assault on America as a racist and imperialist juggernaut has drawn into its wake a raft of revisionist views of Virgil’s work. Awash in woke assumptions about the West, critics don’t have much to say about some of the key elements of the story, such as virtue, sacrifice, and faith. “Two thousand years after its appearance,” writes Daniel Mendelsohn in The New Yorker, “we still can’t decide if his masterpiece is a regressive celebration of power as a means of political domination or a craftily coded critique of imperial ideology.”

It does not occur to the leftist literati that there are other, legitimate ways of appreciating Virgil’s achievement that avoid these crude tropes. The English classicist Bernard Knox, for example, identified three major virtues on display in the work. All of them, it turns out, are essential for republican government.

This piece originally appeared in the National Review