Some four decades ago, Deng Xiao-ping, the paramount leader of Communist China, took command of a country that had been nearly wrecked through Mao Zedong’s radical Marxist experiments like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution and announced a new economic policy of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Many experts in the West predicted that political liberalization would soon follow the economic “liberalization” initiated by Deng. Others were skeptical that the Communist Party would relinquish any meaningful degree of its political power. After all, they noted, Deng stressed that “we shall adhere to Marxism and keep to the socialist road.”

Has Communist China become more liberal with the passing of the years? Has it demonstrated a willingness to respect the political and human rights widely honored by the world community? It is a critical question for the United States whose president has declared that U.S.-China relations are “perhaps” the best they have ever been. Is the curve in Communist China pointed up to freedom and democracy or down to Marxism-Leninism and totalitarianism?

There is disturbing evidence of the latter course. Consider China’s aggressive attitude toward Hong Kong and its activity in the South China Sea, its efforts to bully the island democracy of Taiwan into accepting it is a province of China, the onerous conditions attached to its large loans to cash-hungry nations in Asia, Africa and Latin America, its blatant theft of the intellectual property of U.S. companies doing business in China. Is the People’s Republic of China on its way back to totalitarianism?

One widely accepted way of measuring a nation’s place on the political spectrum is to apply Zbigniew Brzezinski’s six traits of a totalitarian state: an official ideology, a single political party typically led by one man, a secret police, party control of mass communications, party control of the military, and a centrally directed economy. Where is Communist China headed?

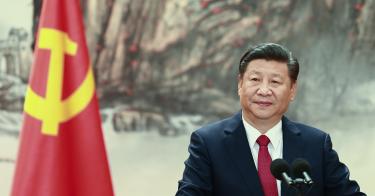

China is ruled by an official body of socialist doctrine that covers all aspects of society. At the 2017 party congress, the Communist Party approved a new phrase for its charter—“Xi Jinping Thought For The New Era of Socialism With Chinese Special Characteristics”—elevating President Xi to the demigod status of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. The Congress’s meeting hall featured enormous side-by-side portraits of Xi and Mao.

Since President Xi rose to power in November 2012, Freedom House reports, Communist China has redoubled its efforts “to exert control at home and expand its influence overseas.” It has established, for example, an extensive surveillance system in China and conducted a sophisticated propaganda campaign abroad.

The Chinese Communist Party is increasingly dominated by one man, Xi Jinping, whose power is stronger than any leader since Mao. At the 2018 People’s Congress, lawmakers passed changes to the constitution abolishing presidential term limits and enabling Xi to rule indefinitely. Just how powerful Xi is can be judged by the vote on the constitutional change—2,958 in favor, 2 opposed and 3 abstaining. The change in the duration of the presidency aligns that office with the other positions Xi holds—head of the Communist Party and of the military, neither of which has term limits. Since taking power in 2013, Xi has centralized his authority, ousted internal political enemies, and backed policies to tighten control of civil society.

Beijing depends upon a system of police control supervised by the leaders of the Communist Party and directed against all “enemies” of the regime. Although denied by the regime, the laogai system of prisons and labor camps still exists and is populated by political prisoners. According to Human Rights Watch, the government has detained and prosecuted hundreds of political activists and human rights defenders. The unexplained disappearance and subsequent confession of two high-profile citizens—actress Fan Bingbing and vice Minister Meng Hongwei—demonstrated that China’s legal system has its own set of rules.

According to the BBC, forced disappearances are nothing new in China. Days or weeks may pass before the government confirms the person is being held and details the charges. Eventually there is a public confession followed by jail or a penalty: Fan Bingbing, who appeared in 2013’s “Iron Man 3,” was fined an extraordinary $129 million for evading taxes. Despite legislation that bans torture, the practice remains widespread. Since Xi became China’s leader, dissent has been systematically reduced, and loyalty to the nation—and the Communist Party—has become the prime imperative.

Through its 90 million-plus members and an almost unlimited budget, the Chinese Communist Party controls all means of mass communication, particularly the electronic media. The Party has developed a sophisticated system of monitoring—the social credit system—that collects information on academic records, traffic violations, social media, friendships, adherence to birth control regulations, employment performance, and consumption of food and drink. As the State Department says, the system is calculated to promote self-censorship. A person’s “social credit score” estimates his loyalty to the government; it also creates incentives for citizens to police each other. The temptation to create a nation of informers is enormous.

The majority of the Chinese people know only what they read or hear or see on the government-run media. They believe there was no such thing as the Tiananmen Square massacre, only an instance of police being forced to arrest and jail a bunch of so-called “hooligans” to preserve the peace. According to Reuters, the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre is an occasion for a cat and mouse game as people use more obscure words on social media sites, with obvious allusions immediately blocked. Some years, even the word “today” has been erased.

Two years after the death of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo, the government continued to censor an array of words and images associated with Liu in the public media and on social media platforms. According to the State Department, phrases like “rest in peace,” quotes from his writing, and images of candles were blocked online and in private messages sent on social media. The government closed 128,000 websites in 2017 for their “inappropriate content,” particularly criticism of Xi and his regime.

The government and the party are especially sensitive to the activity of Christians, Muslims, the Falun Gong and other believers. In April 2018, Cui Haoxin, a Muslim poet, was placed in an internment camp for one week for the political views in his poetry. Subsequently, Cui was warned by the police to stop posting information about the camp, whose existence the government denied. It is reliably estimated that as many as two million Uyghurs have been placed in reeducation camps.

Beijing does not hesitate to monitor media far beyond its national borders. The manager of Australia’s largest independent Chinese-language newspaper described the pressure that Chinese officials applied to the paper’s advertisers in an attempt to silence its critical views.

A preacher at a state-run Protestant church in southern China described how the government went about transforming the church into an instrument of the regime. It dismantled crosses, ordered the national flag to be displayed, installed surveillance cameras, and as a last step replaced the Ten Commandments with Xi Jinping Thought.

The most shocking case of persecution involves the spiritual group, the Falun Gong. Meeting in London, a panel of distinguished British lawyers and medical experts concluded that Communist China is murdering members of the Falun Gong and harvesting their organs for transplant. Beijing has repeatedly denied any such practice, but admits it used organs from executed prisoners in the past but stopped doing so in 2015. However, the London panel concluded it was “satisfied” that the practice of forced harvesting of organs has continued with imprisoned Falun Gong members. The panel chairman said that “many people have died indescribably hideous deaths.”

As the PRC continues to challenge the U.S. as the world’s largest economy, so too does the Communist regime increase its military strength to protect China’s overseas interests and establish itself as a major power in Asia and beyond. Since 2000, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, China has built more submarines, destroyers, frigates and corvettes than Japan, South Korea and India combined. Its first domestically designed aircraft carrier took only five years to build. (The U.S. takes as long as 10 years from design to launching.) A restructure of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is scheduled to be finished this year, making the 2-million-strong PLA “leaner but mightier,” in the words of Zhou Bo of the Chinese Ministry of National Defense. ” All major military decisions are approved by the central committee of the Communist Party, in accordance with Mao’s axiom, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

Visitors to China are inclined to think, after their first look at the dozens of skyscrapers in Beijing, Shanghai and other Chinese cities, that the PRC economy is too successful to be communist. That was my initial reaction on my trip to China a decade and a half ago, causing me to dub Beijing “The City of a Thousand Skyscrapers,” an appellation my Communist hosts loved and often quoted. I subsequently learned that the skyscrapers were owned by either the Party, the PLA or the sons and daughters of the party elite. China has 51,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) employing 20.2 million people that are kept float by substantial government subsidies. They constitute a major budget item: SOEs account for the majority of China’s top 500 firms.

Socialism with Chinese characteristics is not soft democratic capitalism but hard market socialism in which critical decisions are made by the Communist Party not the market. China’s economic growth is due to several factors, including its very loose adherence to the rules it agreed to abide by when it joined the World Trade Organization; the remarkable work habits of the Chinese; the allure of the 1.4 billion Chinese as a market to the Western businessman; and the ability of the Communist Party, so far, to balance the demands of a mixed economy.

As we can see, China is already totalitarian in five of the six traits developed by Brzezinski to determine a totalitarian regime. Only with regard to a centrally controlled economy do we find an authoritarian rather than a strict totalitarian structure. Human Rights Watch has been persuaded by this capitalist tilt to describe China as “a one-party authoritarian state that systemically curbs fundamental rights.” )The U.S. State Department says that “the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the paramount authority.”

But there is no sign that Communist China is becoming more liberal in its ideology, one-party politics, control of the military, censorship of mass communications, use of secret police, and suppression of speech and religion. By any reasonable measure, the PRC is becoming a totalitarian state whose actions are dictated and determined by Xi Jinping and the Communist Party he heads.

To say otherwise is to ignore the totalitarian behavior of Communist China for the past four decades and to doubt that a despot like Xi will do whatever is necessary to maintain his power and control.

Does this mean that the U.S. should not do business with China? No, it means that the U.S. in its trade and other dealings with the PRC should proceed from the understanding that China is ruled by a regime that is not liberal or socialist or authoritarian but totalitarian in its essence and is headed back to its Maoist roots.

We can draw a lesson from President Ronald Reagan, a lifelong anti-communist, who sat down with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev once he could negotiate from a position of economic and military strength. It is clear that President Donald Trump has done his homework: he has no illusions about Communist China. He is confident he can make China keep its word to increase its purchase of U.S. products and to stop the theft of U.S. intellectual property.

If not, the president will once again apply sweeping tariffs to a wide variety of Chinese goods. And while tariffs on Chinese imports are bad for Americans, they are a brand of Trumpian-style diplomacy that a dictator like Xi Jinping understands very well.

This piece originally appeared in The National Interest