The Asian Studies Center

Introduction: A New View of America's "Near West"

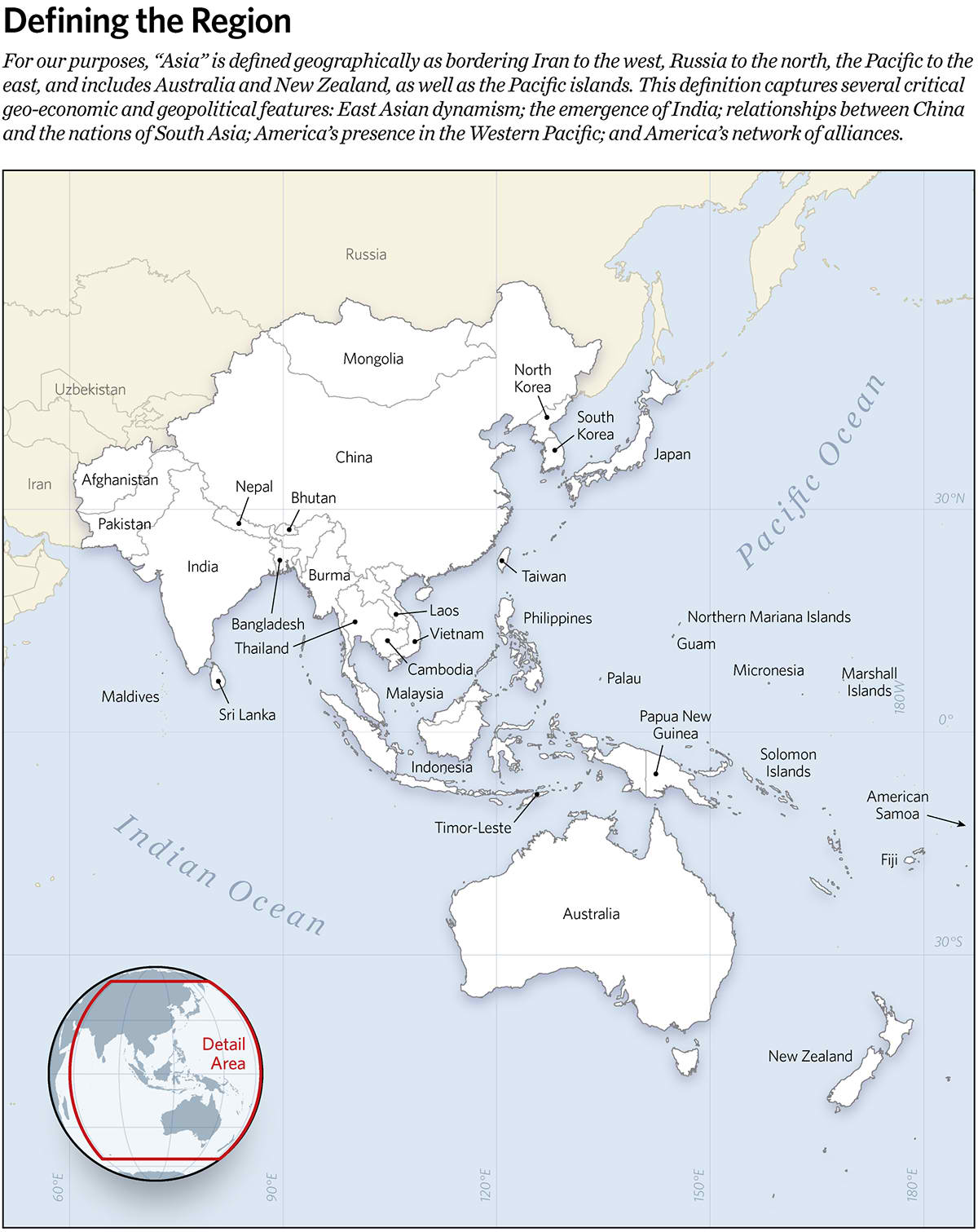

At The Heritage Foundation’s annual B. C. Lee Lecture this year, the Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs summed up perfectly America’s destiny as regards Asia: It is America’s “Near West.” It is hardly the “Far East.” It is not to our east, and in this day and age, it is not really very “far.”

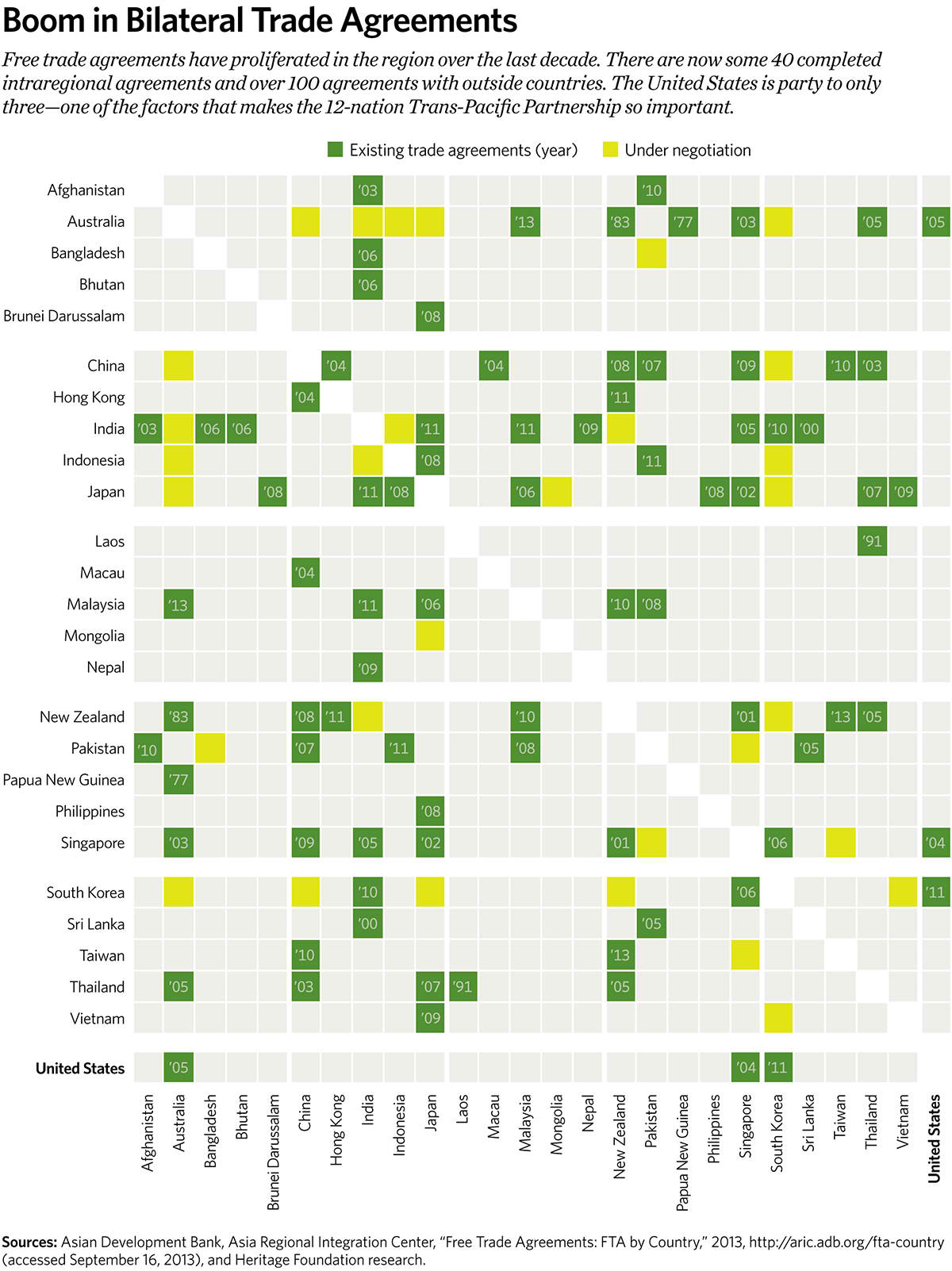

America’s relationship with Asia is long by the standards of our young nation. From the 1833 Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the U.S. and the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), when the two sides agreed to commercial relations “as long as heaven and earth shall endure,” to the 2011 Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, the U.S. has sought freedom of commerce. From its post–World War II security treaties to its sacrifices in war, America’s military and its network of alliances have served as anchors of peace. And although the politics of self-government can be a noisy affair in Washington, our support for liberty makes it through the din. Many millions in Asia would live under tyranny today without the vigilance of the United States. Many millions more rely on our continued leadership to free them.

The stakes involved in recognizing America’s status as a Pacific nation have never been greater. The global center of power and prosperity is moving to our west. And the prospect for instability and conflict that involve the U.S. interest in peace, freedom, and prosperity is moving with it.

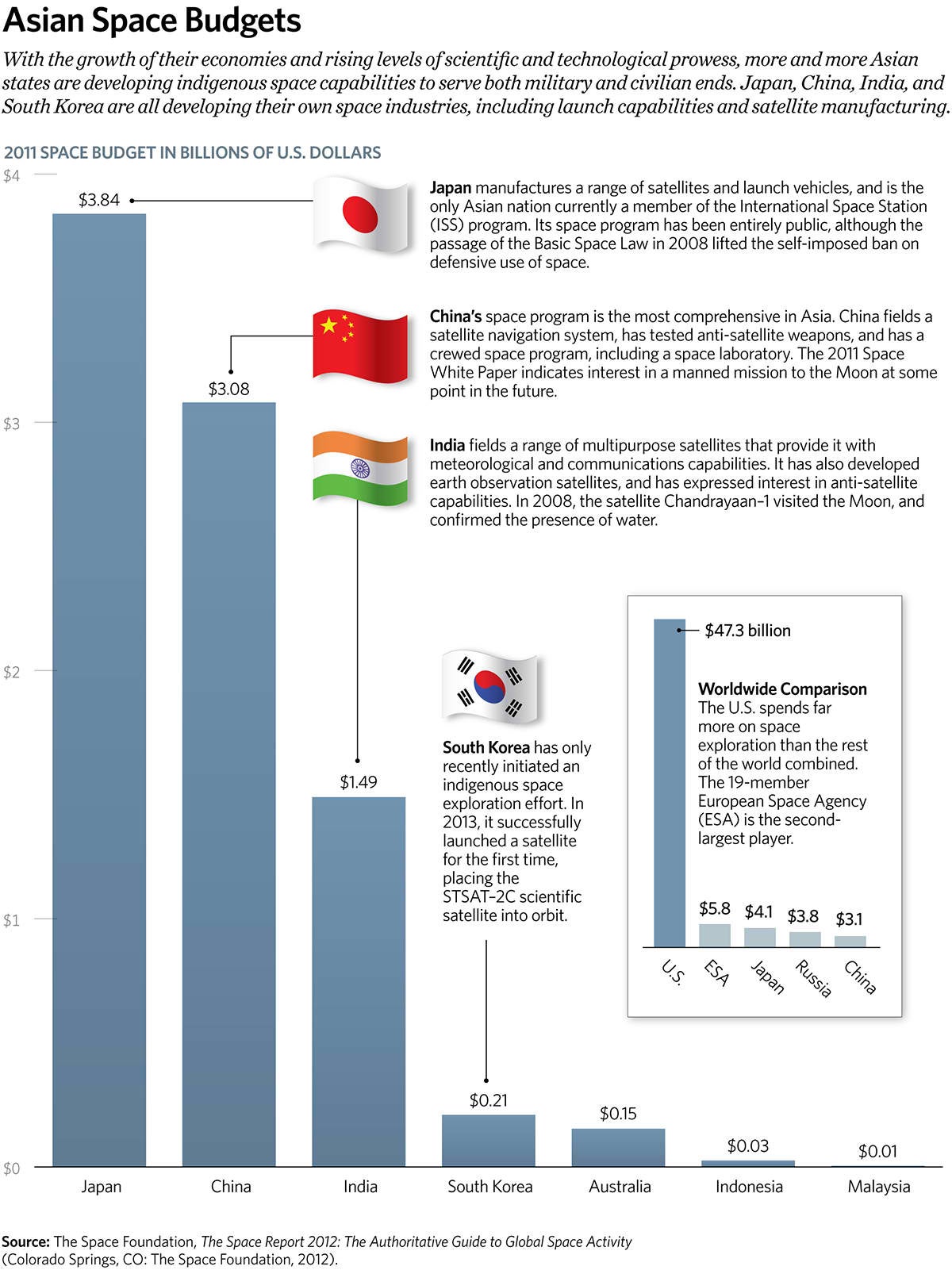

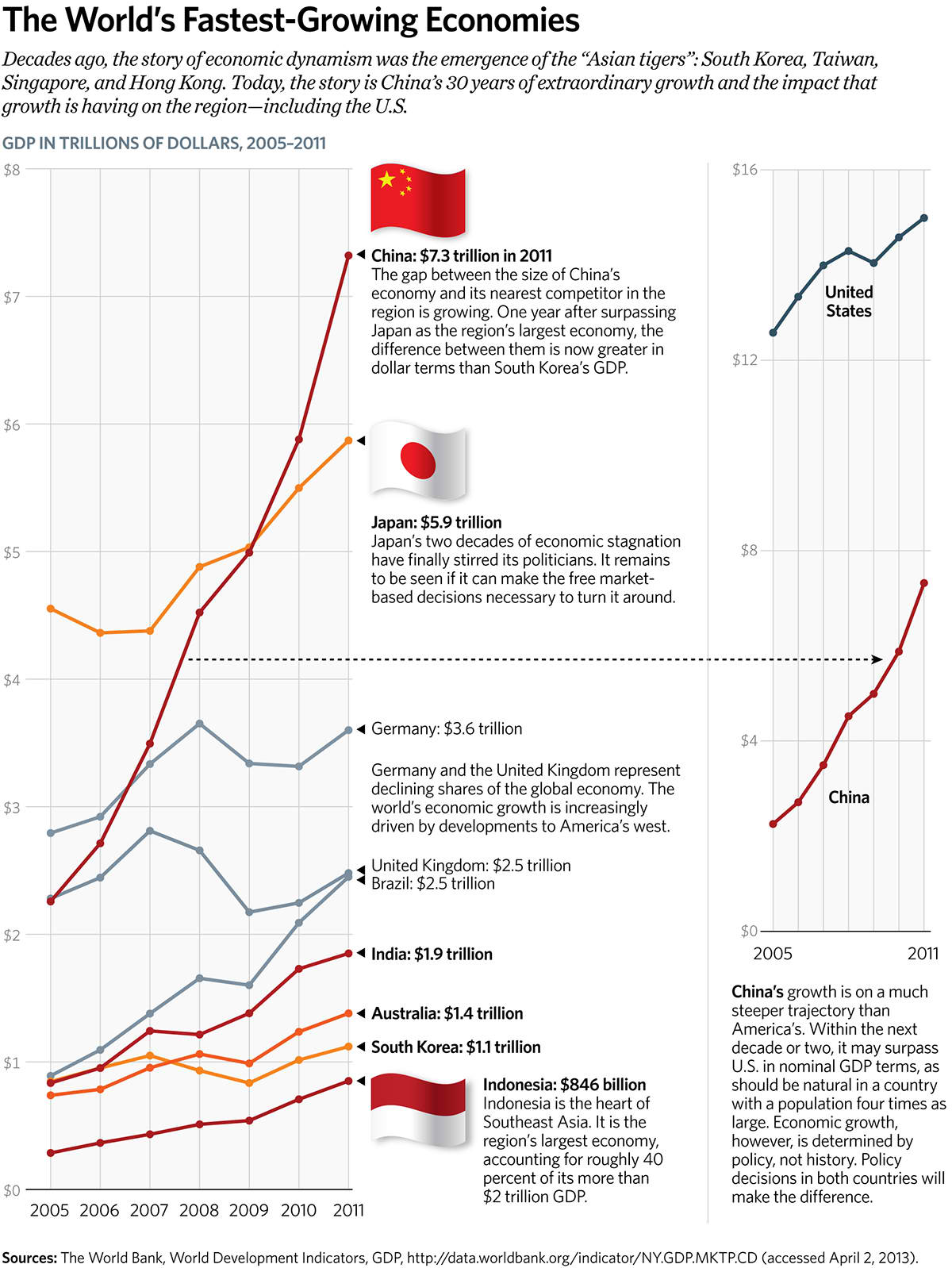

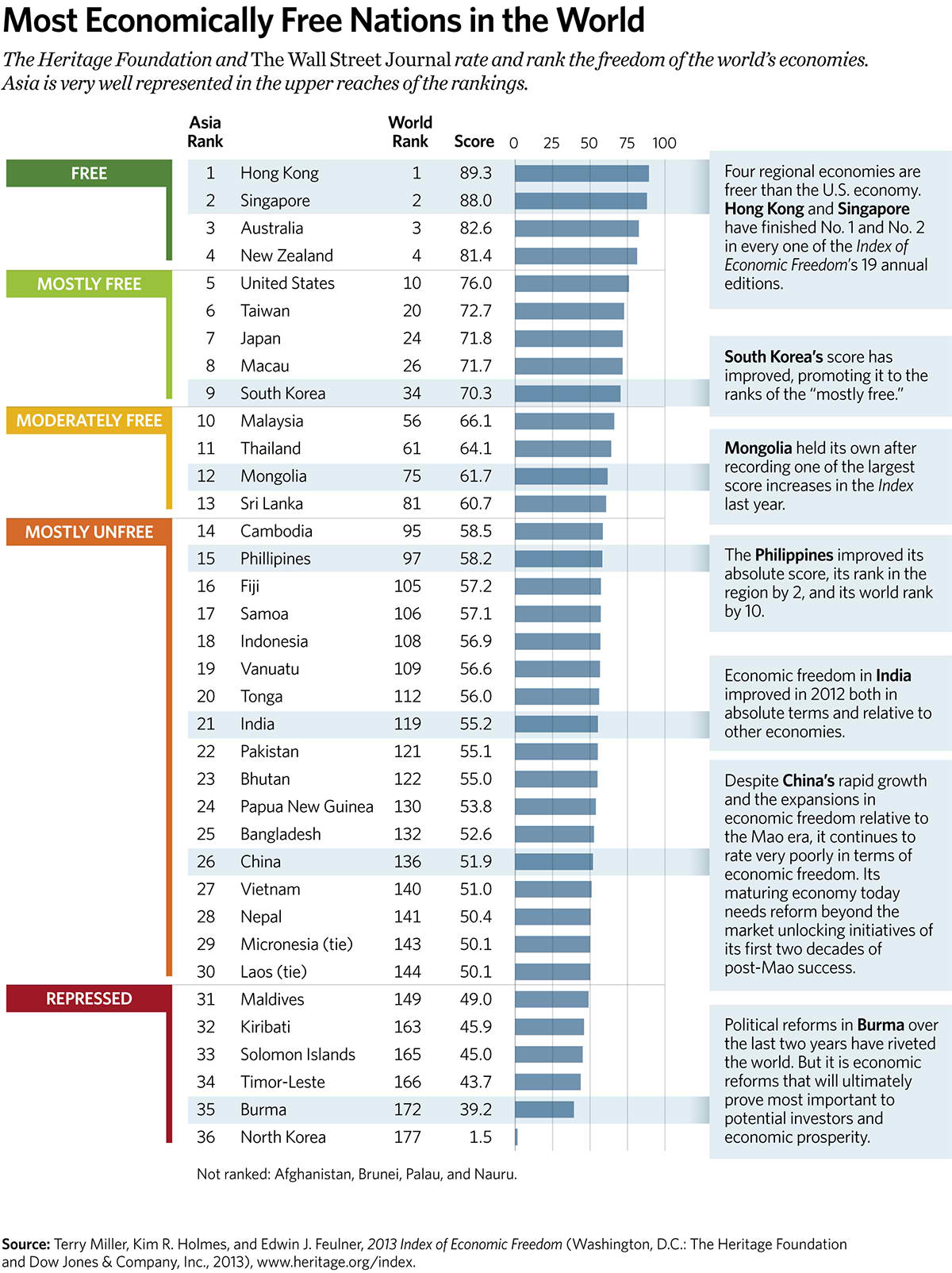

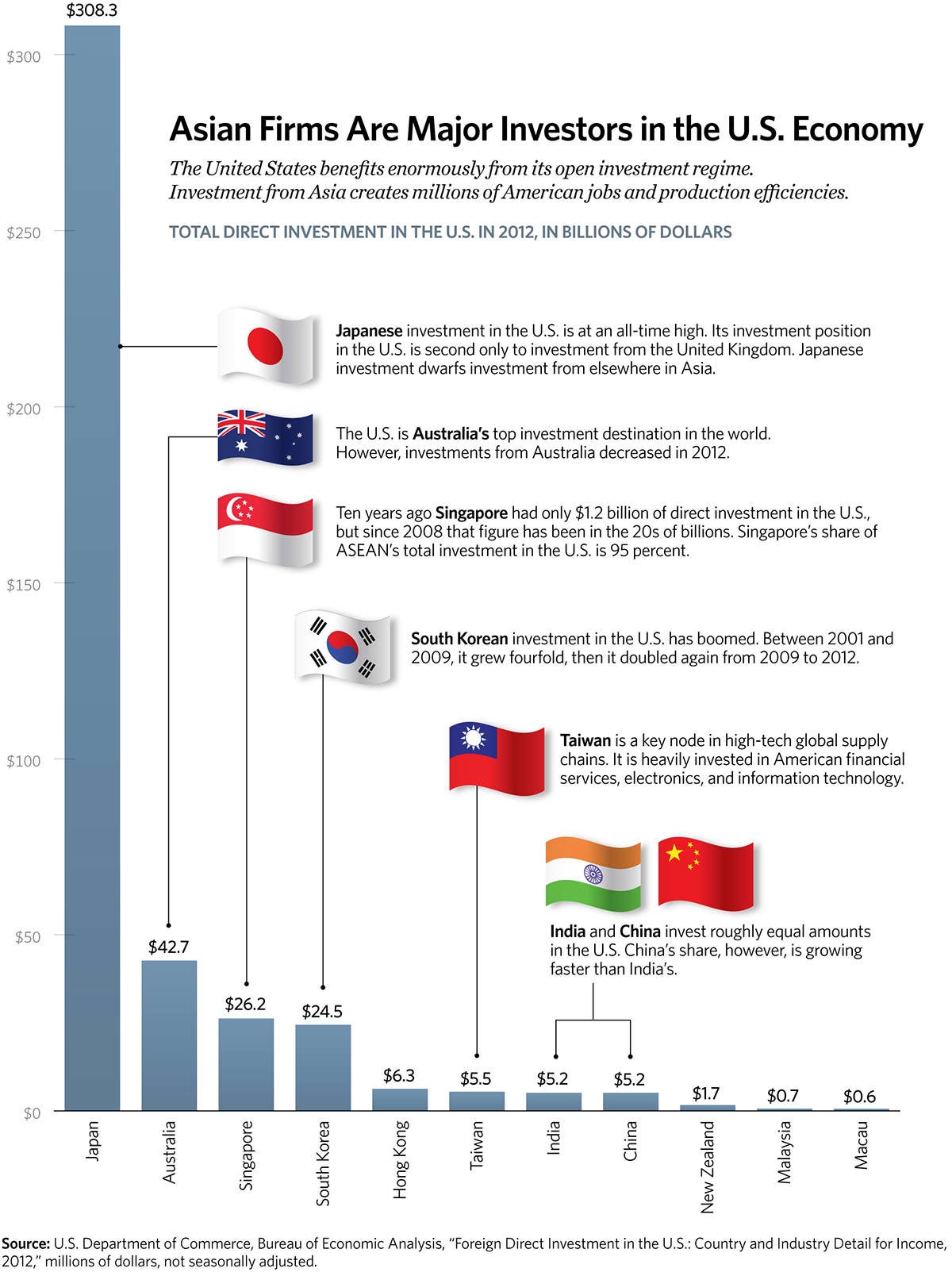

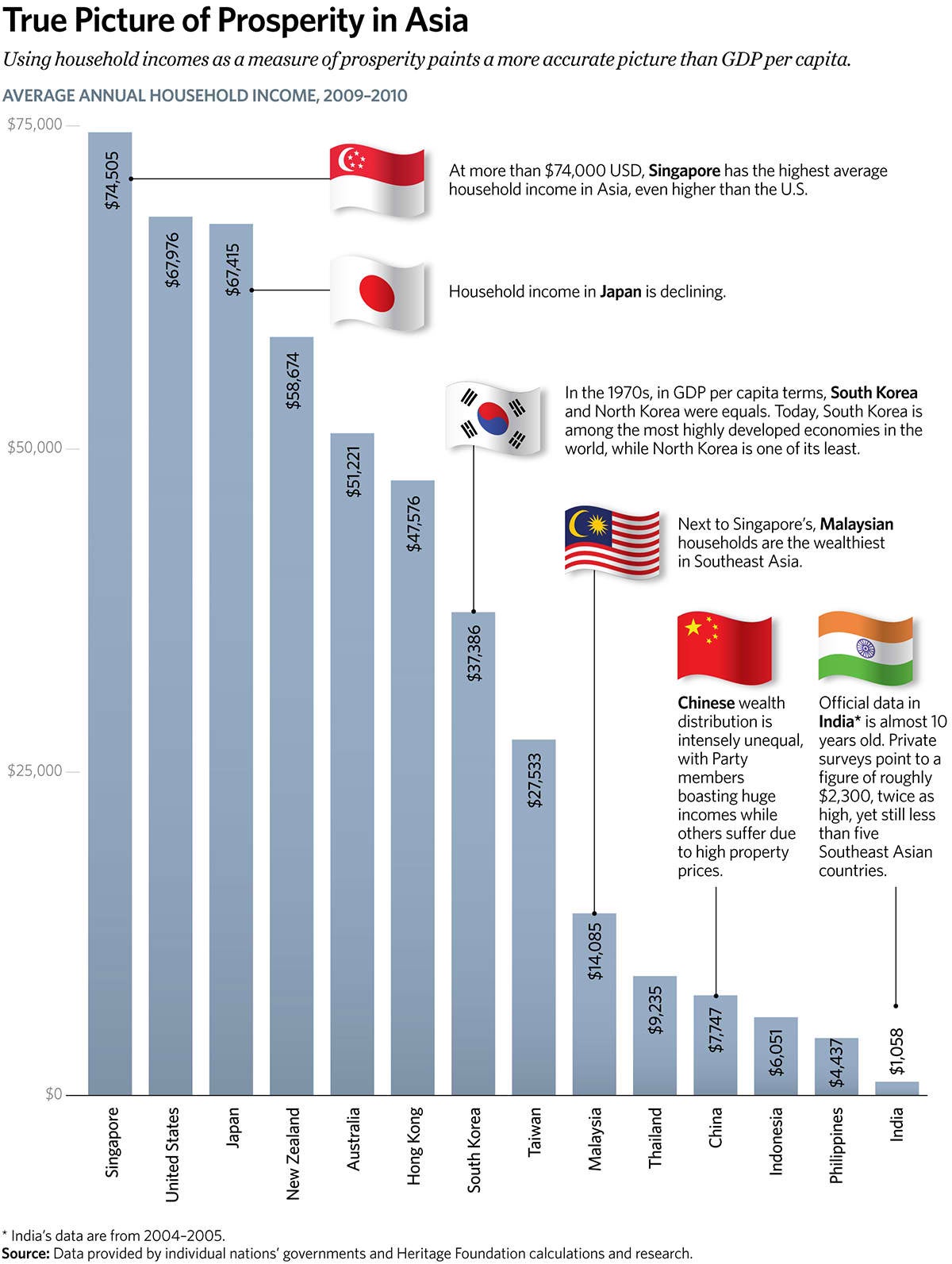

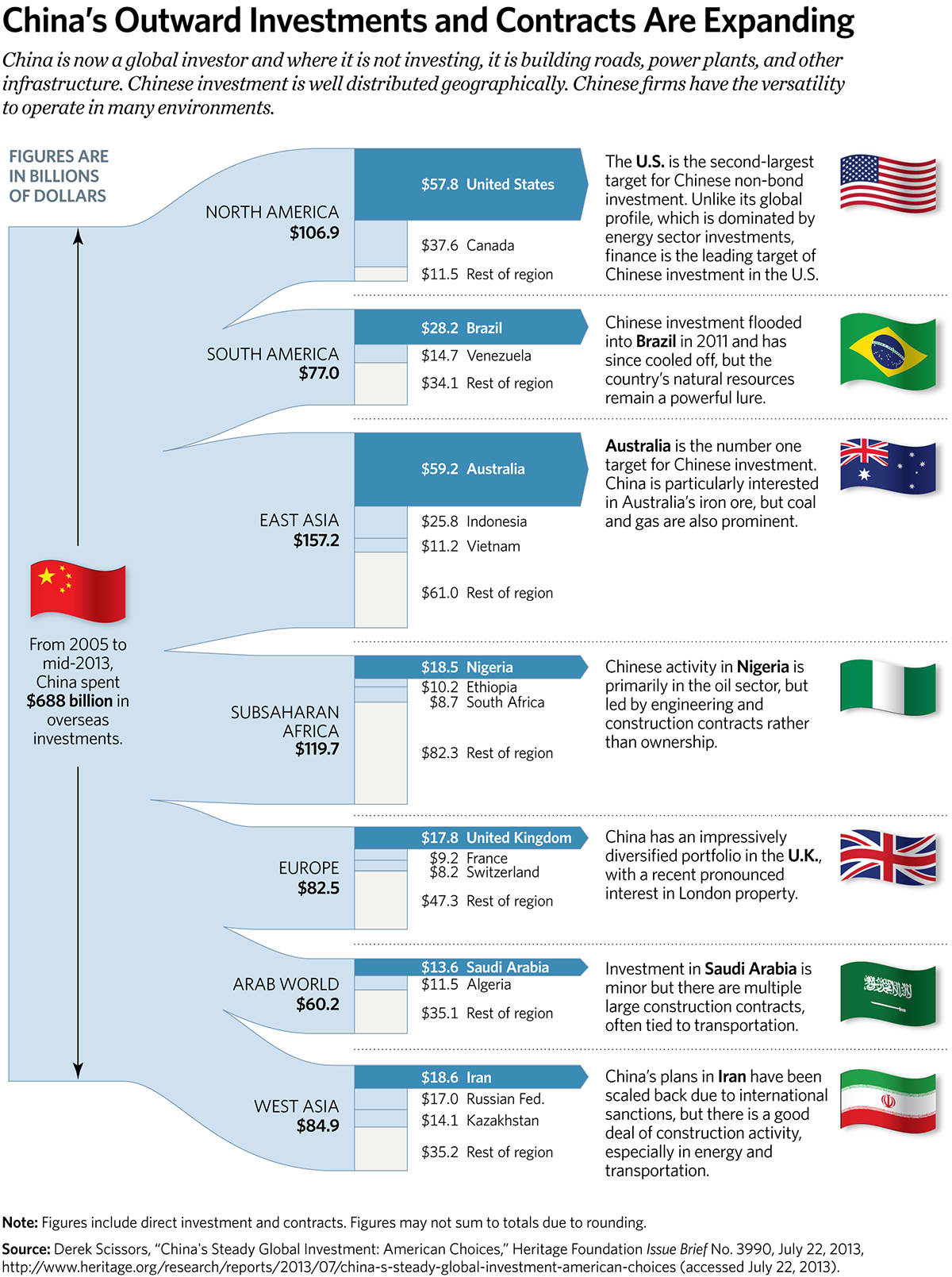

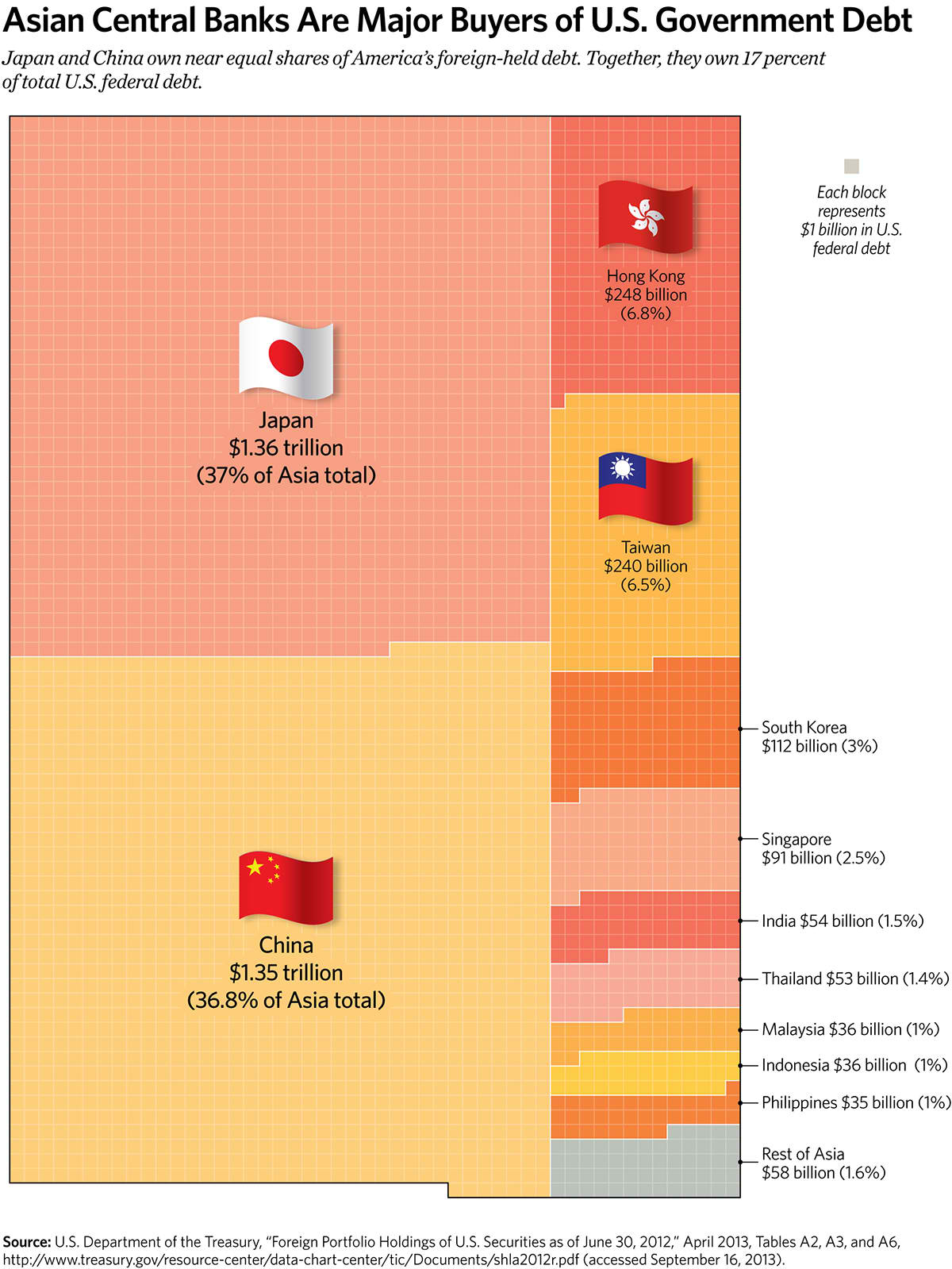

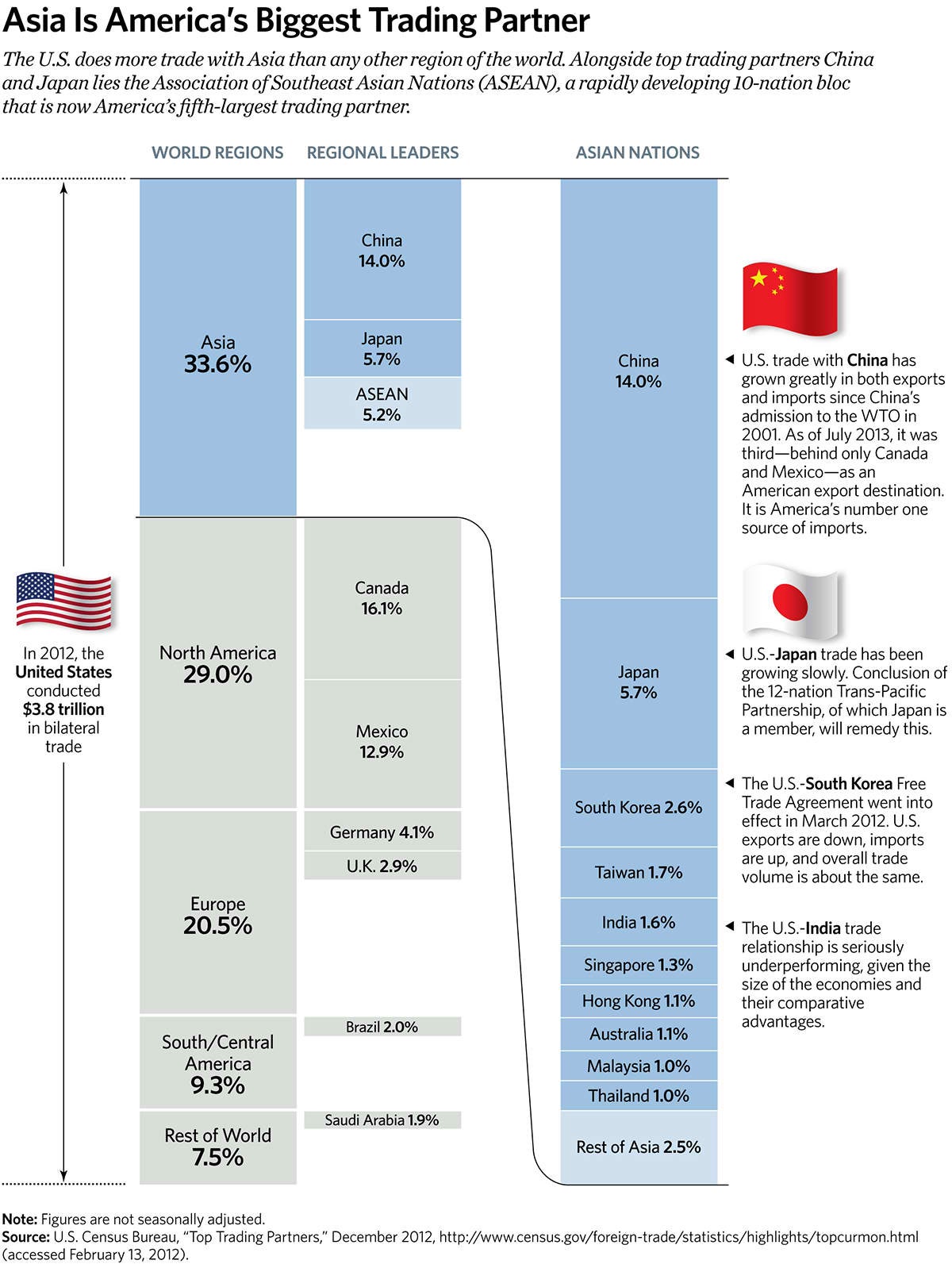

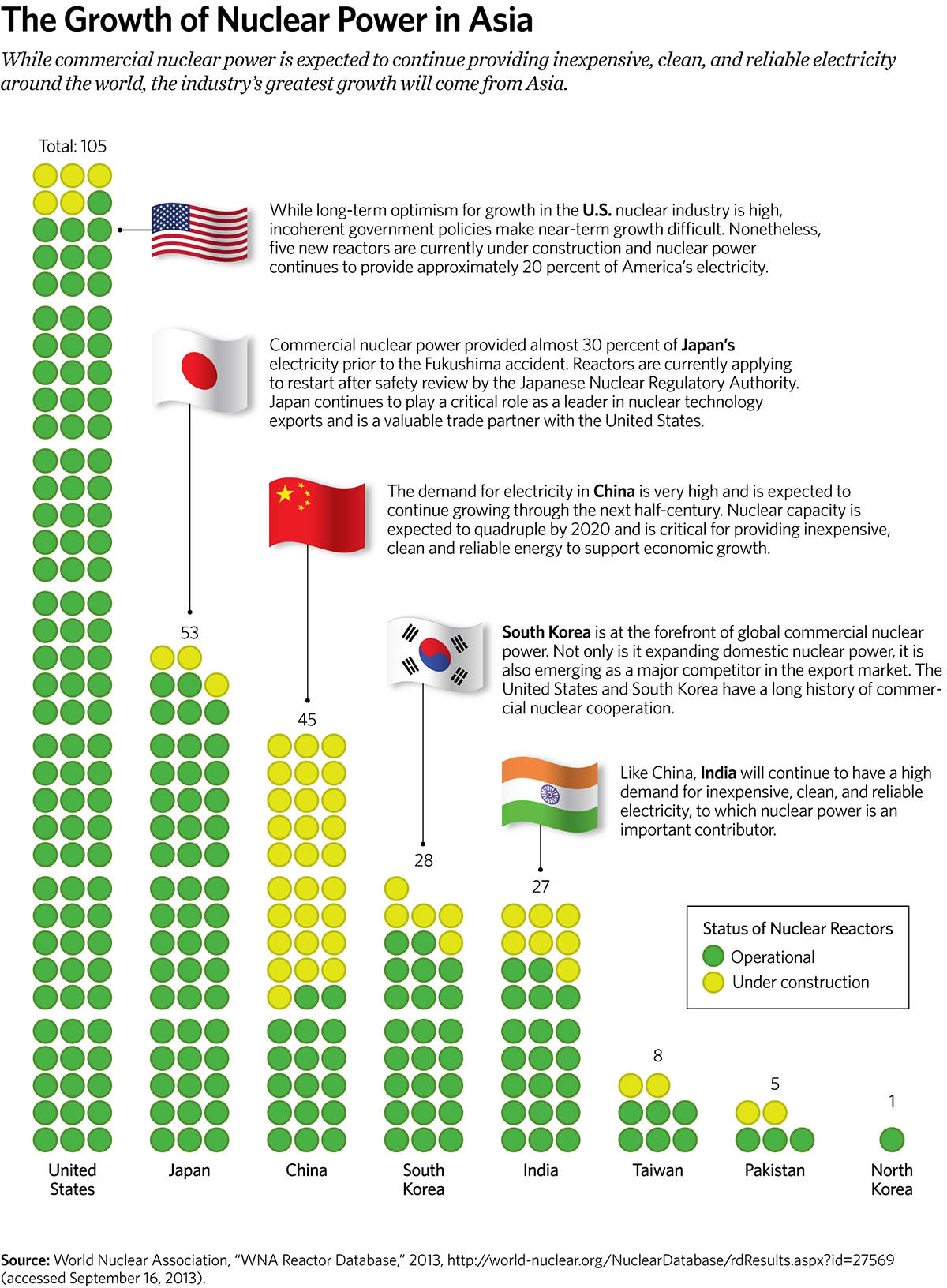

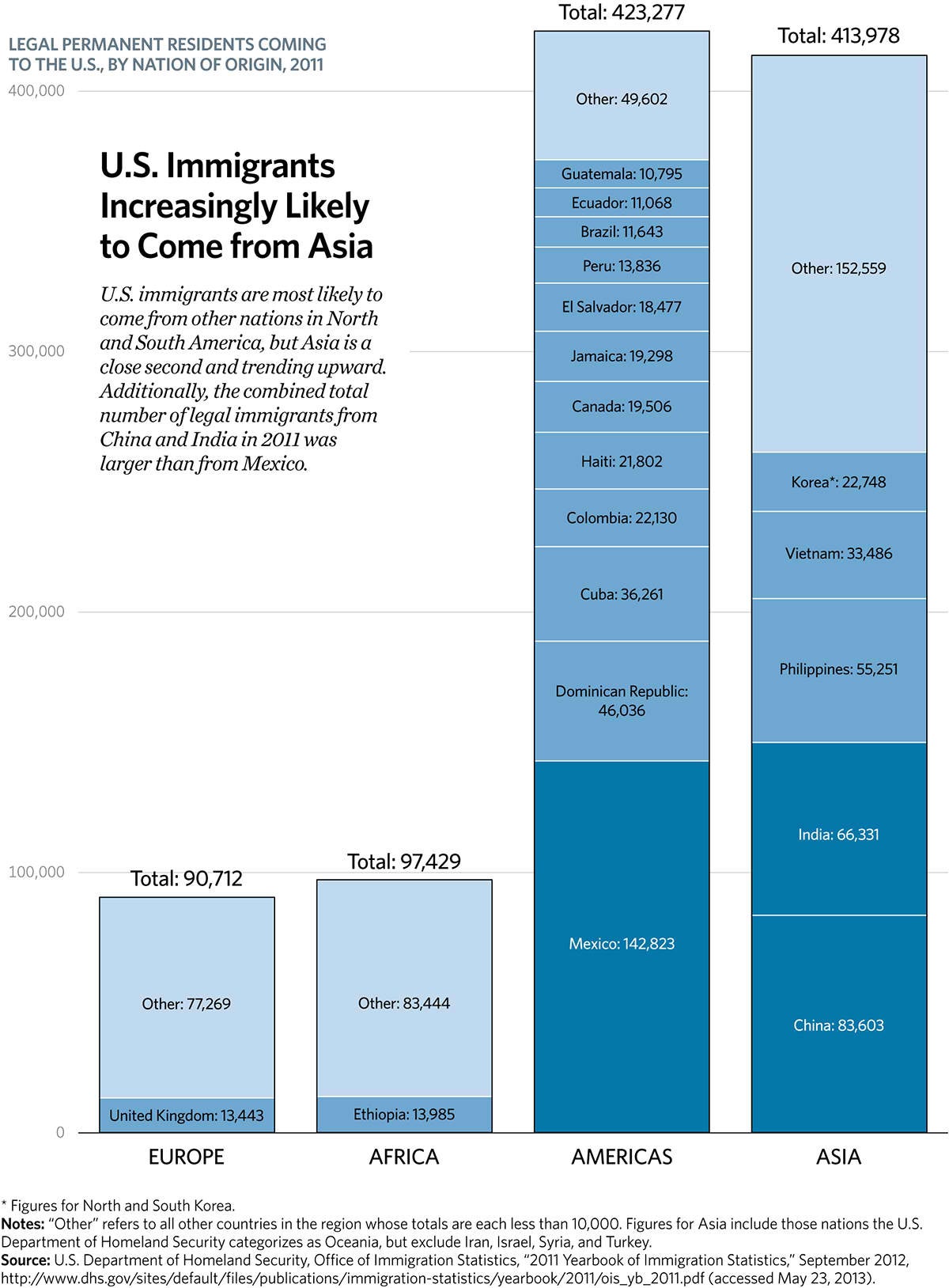

Asia is home to the world's largest and fastest-growing economies and several of the most economically free nations in the world. The U.S. does more trade with Asia than with any other region of the world. Asian firms invest in America in a very big way, creating jobs and economic opportunity. More and more Asians are immigrating to the United States to improve their futures; they, in turn, improve America’s.

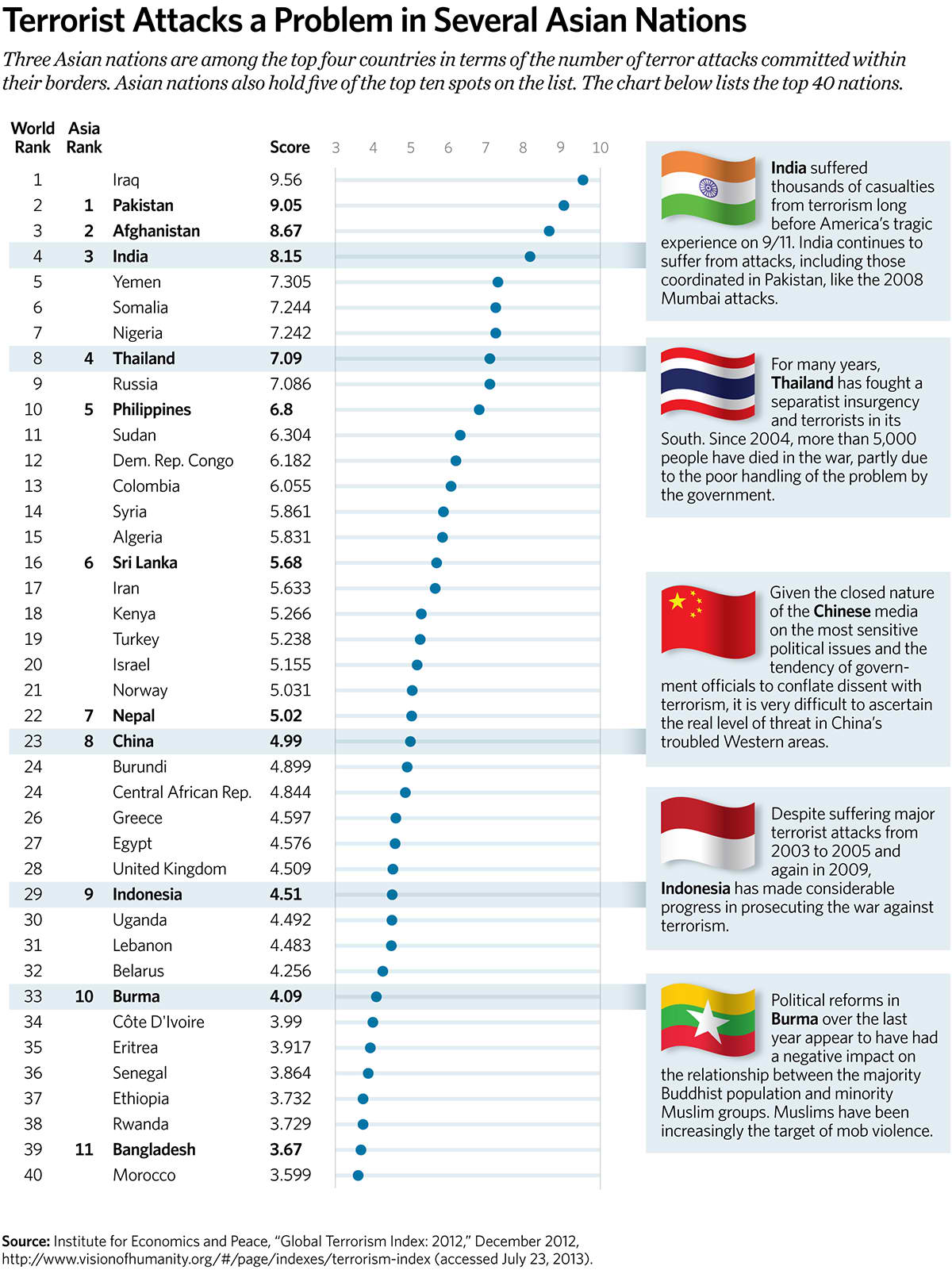

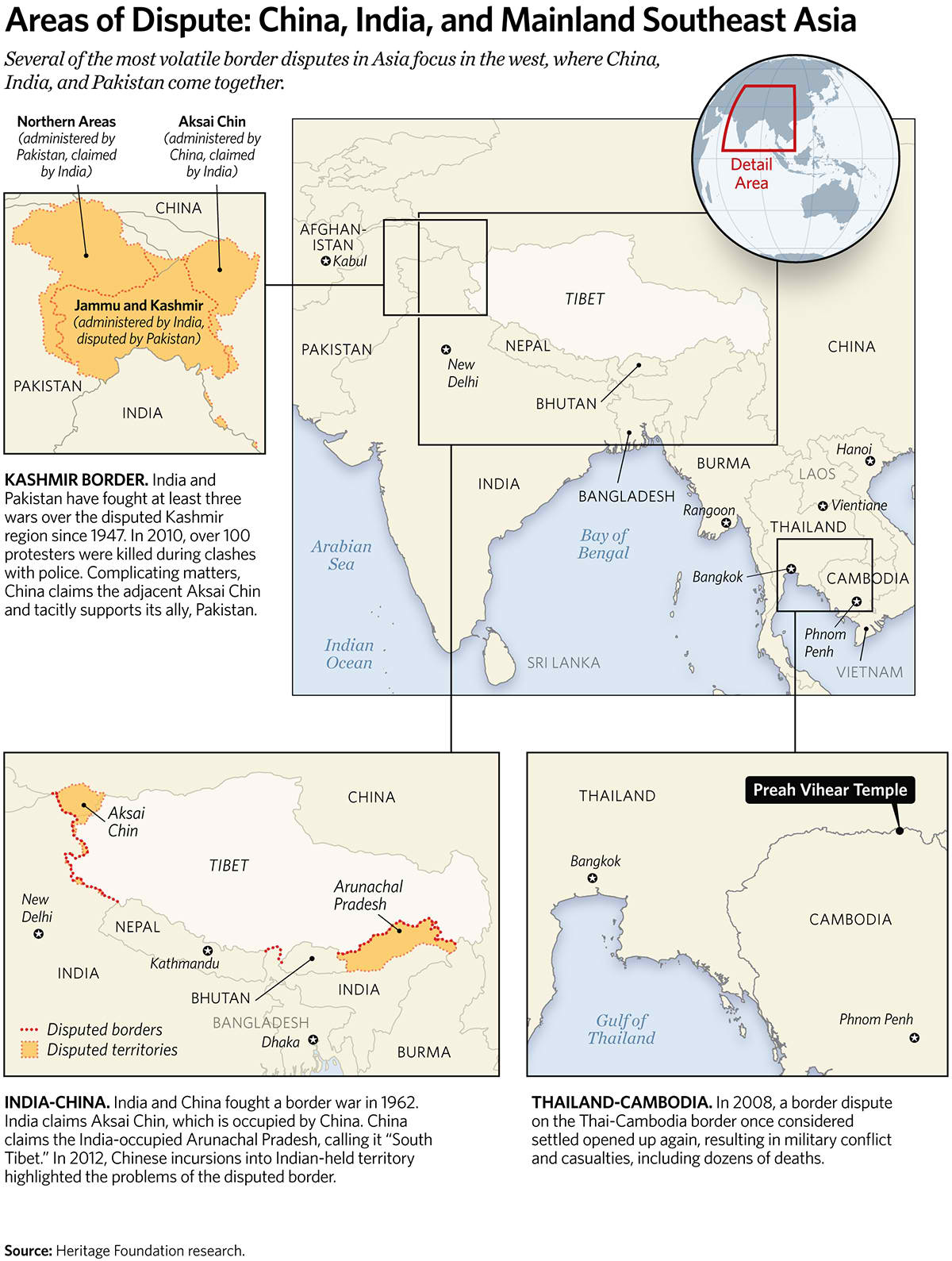

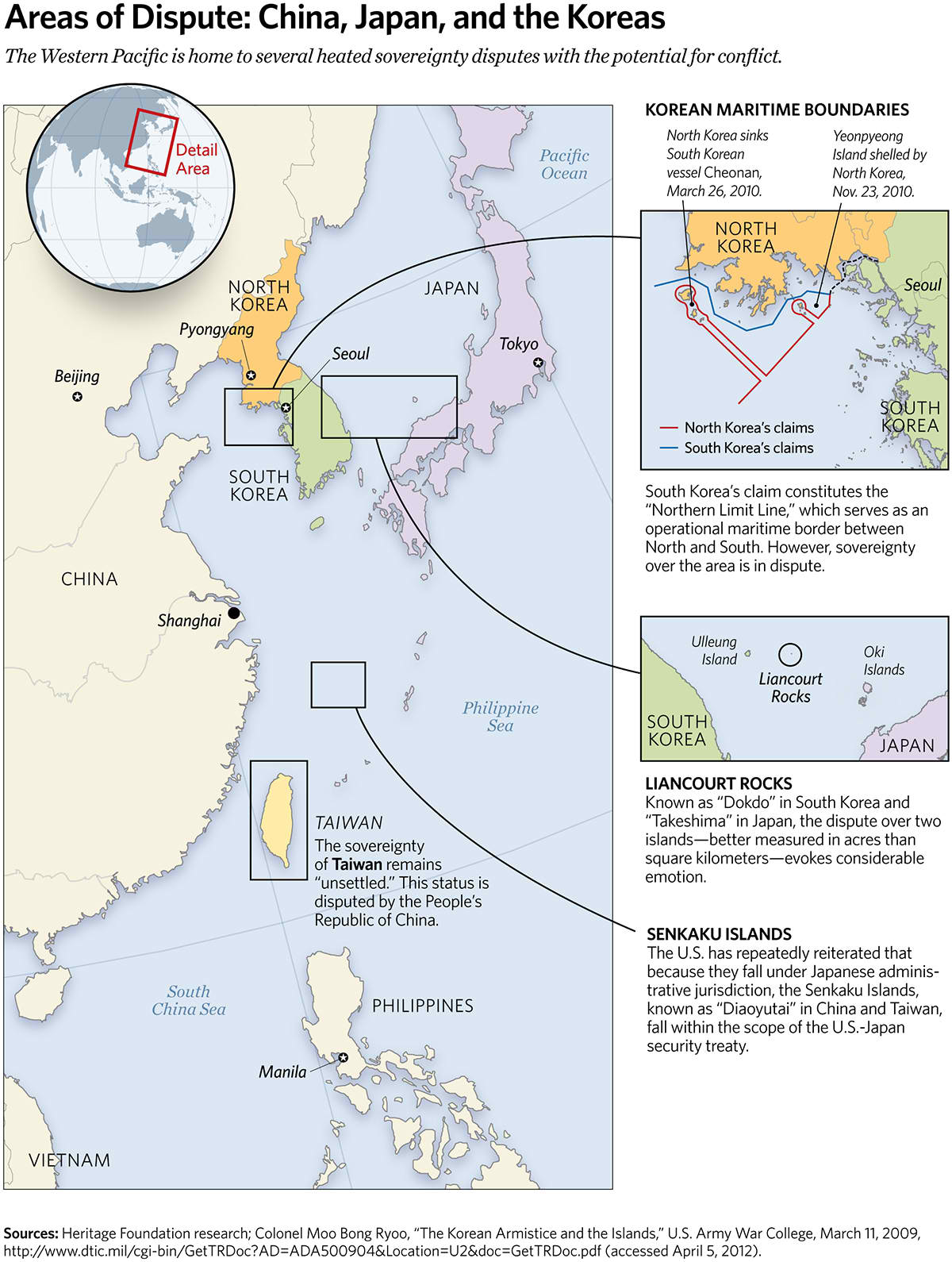

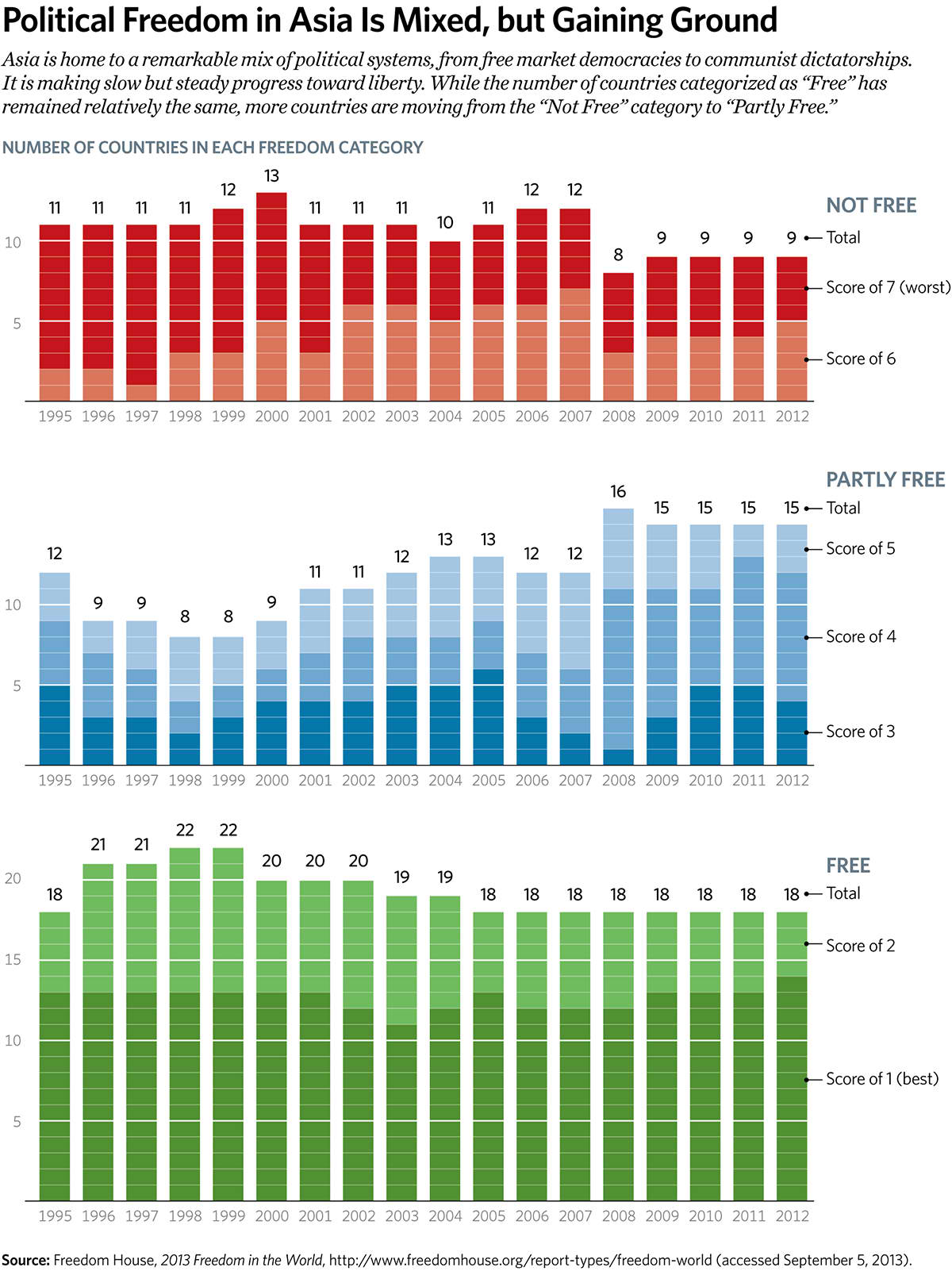

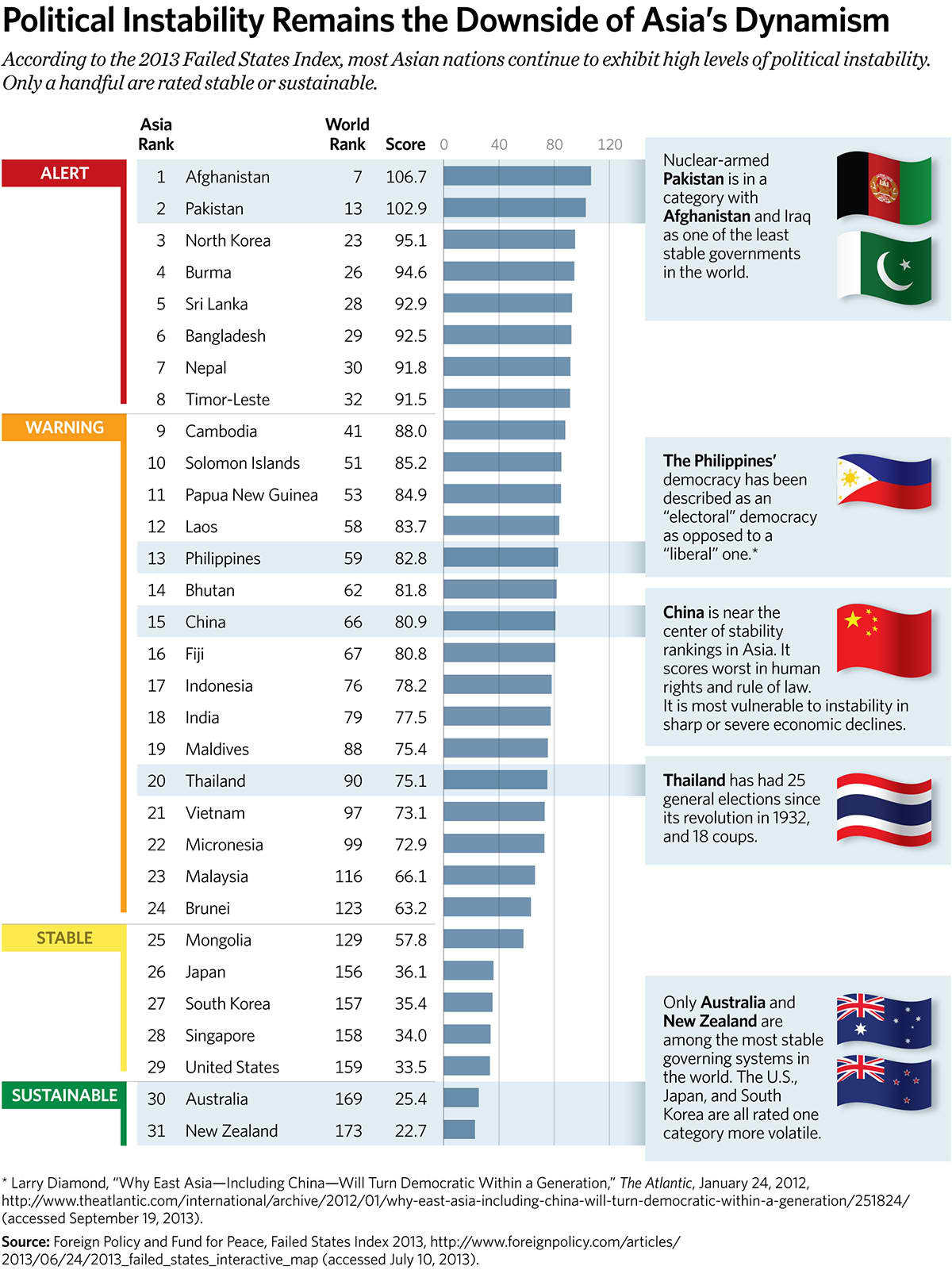

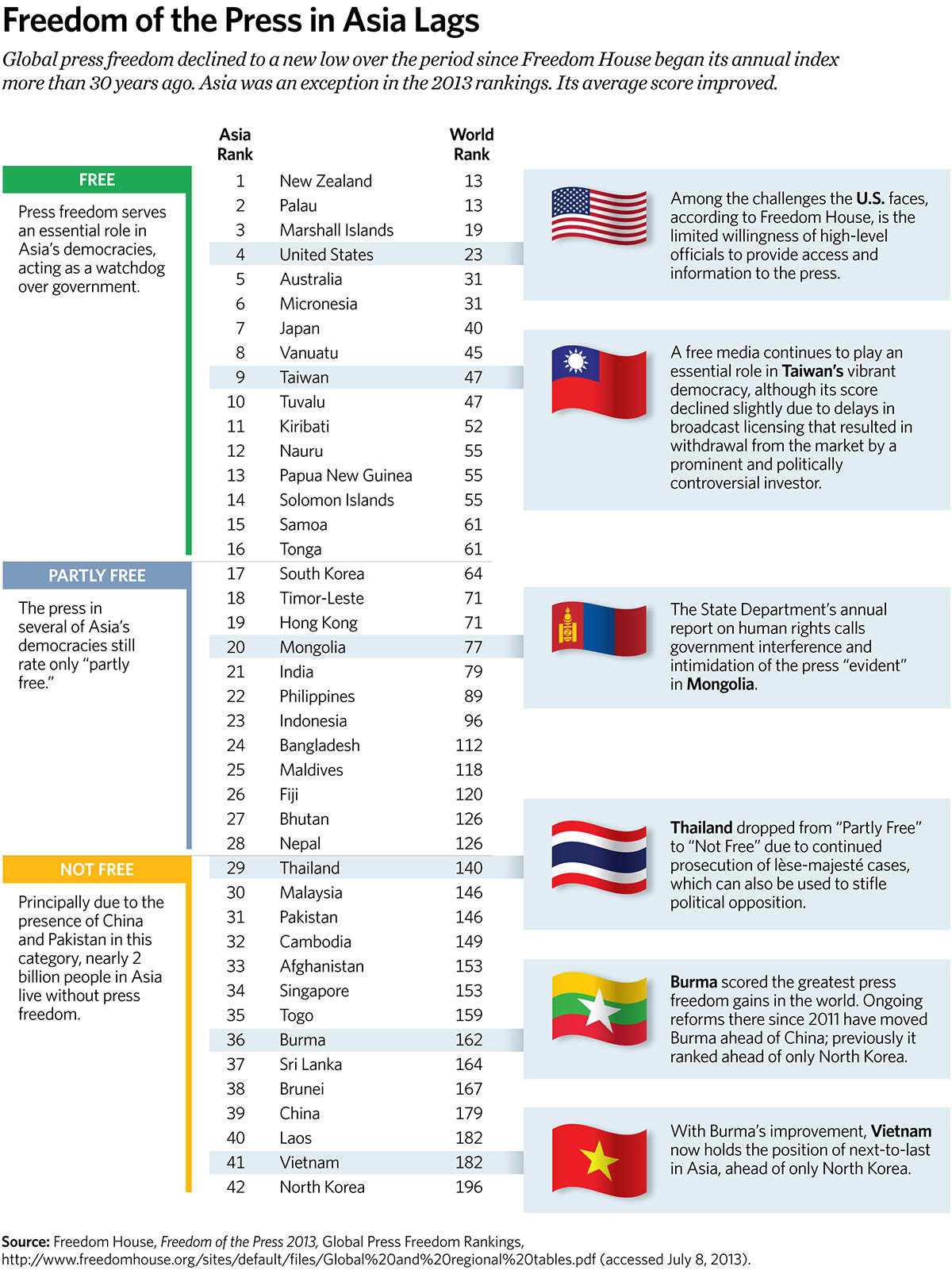

There is also a dark side. Historical tensions in the region threaten to boil over. Borders have been sorting out for decades, but those that remain in dispute—or newly disputed—are major flashpoints. The roots of liberal democracy are not yet very deep. There are alternative models of governance and nightmare regimes. There is also competition for the liberal vision that America has fashioned, and challenges to the predominant American military might that has guaranteed it. History has taught that without its proactive leadership, this volatile mix has a way of drawing America in. Our twentieth century wars in Asia are testament to the tragic results for both America and our friends and allies.

There is tremendous upside to the shift in global power and wealth to the Pacific and America's Near West. For the sake of our own nation, we need to understand and grasp the opportunity. We also need to make the strategic investments and commitments necessary to guard against risk. The upside will not accrue to the U.S. without deep, positive involvement in the life of the region, and the downside will not be managed without our presence.

It is time to take a new view of Asia fully cognizant of all that is at stake in our continuing to carry the responsibility of leadership.

Geography

Economic Stakes

Political Stakes

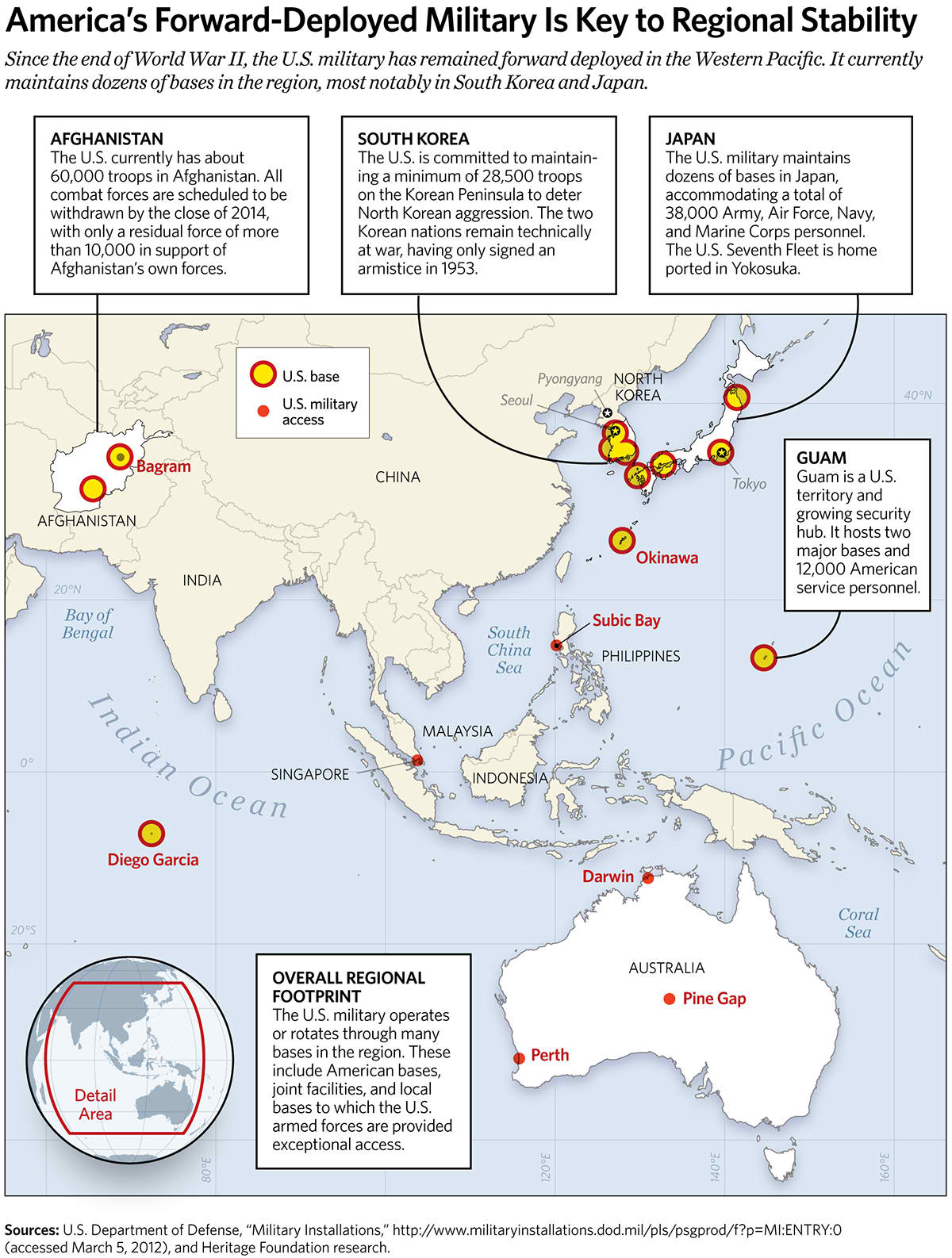

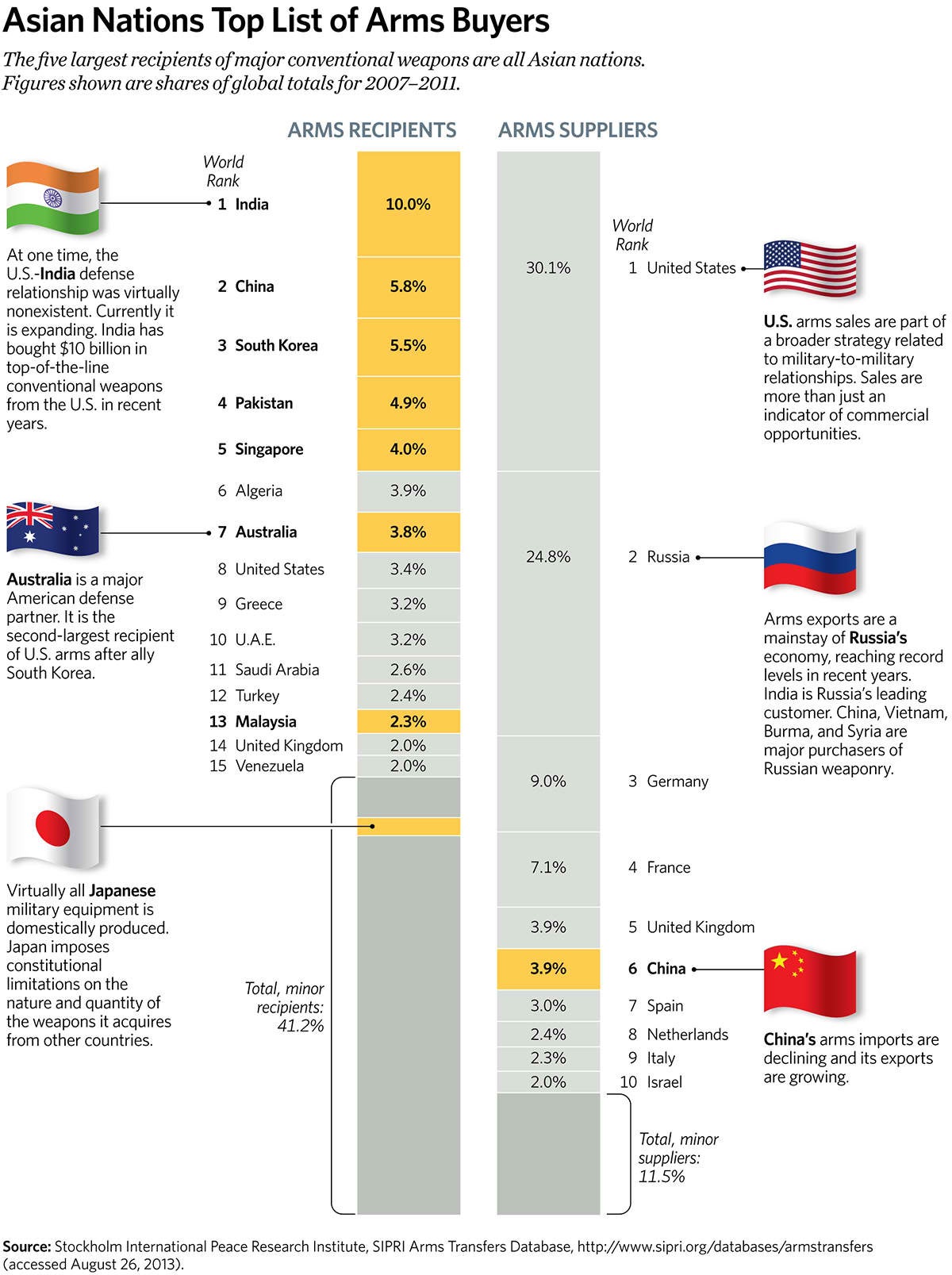

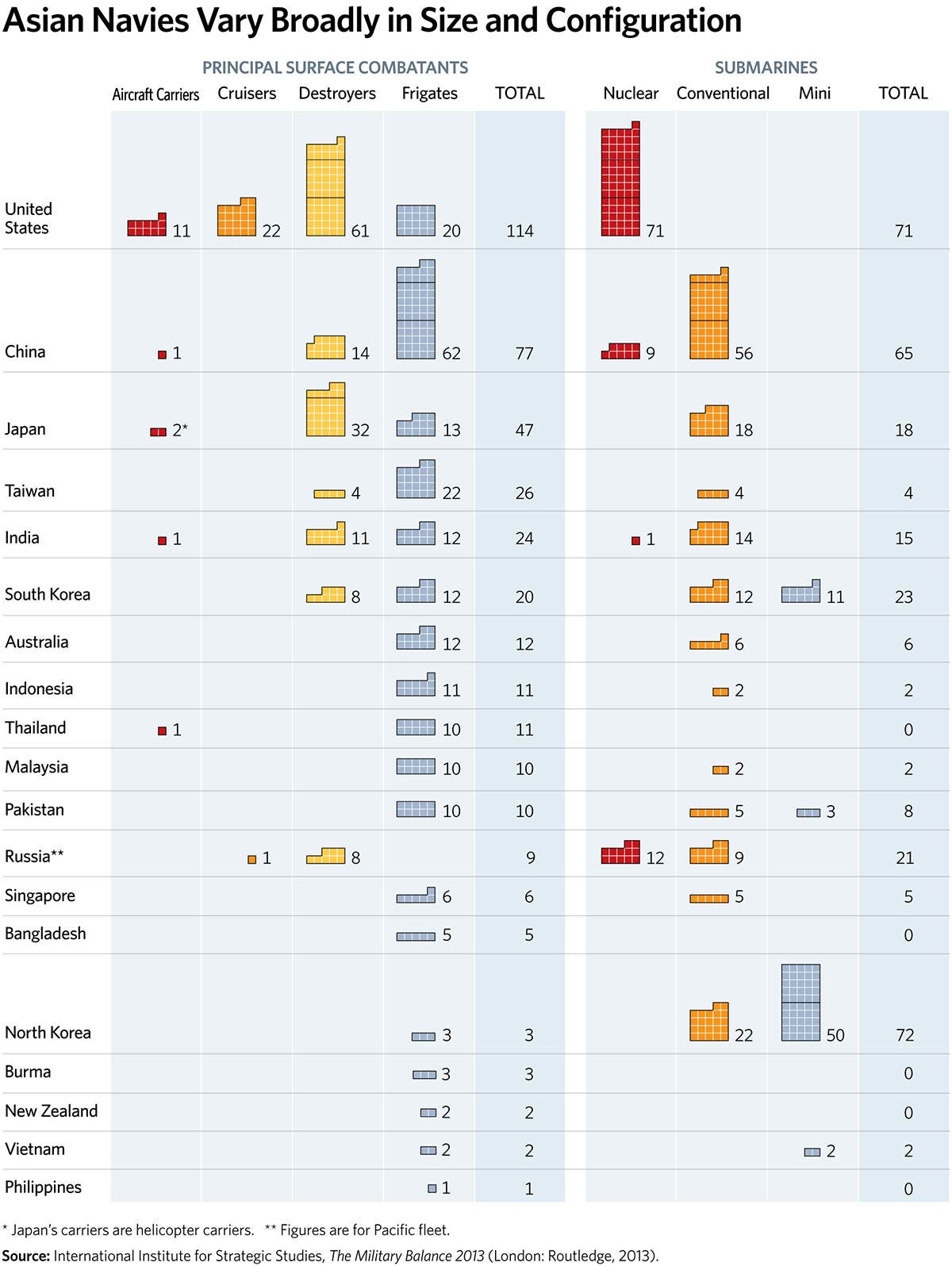

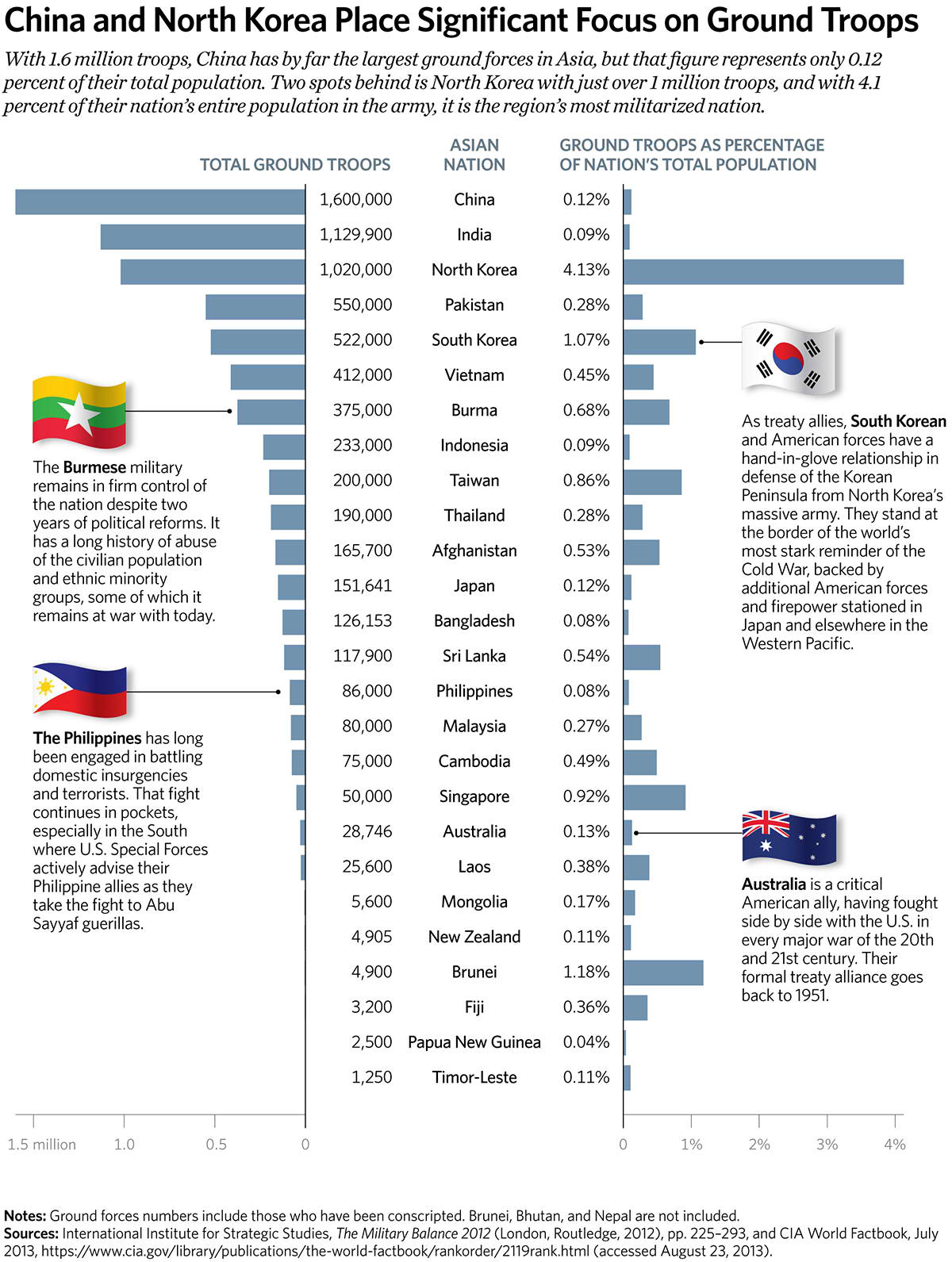

Security Challenges