Executive Summary

The Army has embarked on an ambitious campaign to modernize and transform. Army leaders have made multiple well-conceived changes to drive and facilitate modernization including the organization of Futures Command and the introduction of new modernization priorities. These are thoughtful, but over the course of the Army’s history, modernization has proven challenging—with success shown to depend on the presence of an enduring and powerful vision lasting over the tenure of several leaders. Experience has also shown that the organizational processes and leadership applied to modernization can be just as important as the intellectual basis of the transformation.

In the past, the Army has had the luxury to develop concepts and doctrine based on a single monolithic adversary (e.g., the Soviet Union) operating in a defined geographic area (e.g., Central Europe). The situation today could not be more different, which requires the Army to consider many more potential scenarios and environments. The new National Defense Strategy’s focus on great power competition is helpful, but it should not be interpreted to exclude other regional or counterinsurgency challenges.

This report focuses on the Army. It is the third in the series of Heritage Foundation Special Reports focusing on the future of the U.S. military, specifically providing recommendations to develop the services to deliver increased capabilities by the year 2030.

Despite the multitude of missions the Army is called upon to perform, its core purpose is to fight and win the nation’s wars on land. Predicting the end of conventional war on land is fashionable. Purported experts who regularly forecast the obsolescence of kinetic wars in favor of conflicts featuring cyberattacks, disinformation, and electronic warfare argue for the disinvestment of conventional capabilities in favor of these alternative capabilities. While the character of war is, in fact, changing—and some investment in these capabilities is warranted—it is the U.S. preeminence in warfighting that has deterred outright aggression and maintained the peace. Proposals to shift entirely to new capabilities should be viewed with extreme skepticism.

Background

Providing guidance for Army modernization efforts is the January 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) and Joint Concepts. The NDS signaled a major change in direction to which the Army and other services are still adapting. The recognition that China and Russia are the two priorities for the Department of Defense has major implications for Army force structure, equipment, doctrine, and organization that will take years to incorporate. Joint concepts written in 2012, including the Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, helped set the stage for the Army to conceive of its current concept—the U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)—but now needs an update.

The U.S. Army is the strongest and most capable Army in the world. Nevertheless, it finds itself in 2019 having been shaped by several forces that make the imperative for modernization all the more important. Eighteen years of counterinsurgency (COIN) in Iraq and Afghanistan profoundly shaped Army organizations, equipment, training, leader development, and doctrine. While the Army is working hard to restore the focus on large-scale conventional warfare, it also wisely recognizes the need to retain capability to conduct COIN operations, highlighted by continuing missions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Army budgets and end strength were sharply reduced during the period 2011 to 2016 as a consequence of the Budget Control Act and the prior Administration’s priorities. Readiness was poor, equipment aging, and manpower dwindling. Significant funding increases in 2017 through 2019 have helped the Army change its trajectory, and end strength is slowly growing, albeit constrained by a tough recruiting environment.

Army leaders have gone on the record to say that the Army is too small. Chief of Staff General Mark Milley has said the Regular Army should be in the neighborhood of 540,000 (from 478,000 today) with similar increases in the National Guard and Army Reserve. Additionally, the allocation of forces between its components—Regular, Guard, and Reserve—over time has become distorted, with units whose mission or type are better suited for one component located in another.

Contrary to the common narrative, there have been some great successes in Army equipping during the past 18 years. Army units have been provided with newly designed equipment to help them succeed in COIN environments, including counter–improvised explosive device systems, unmanned aerial vehicles, and body armor. When major programs of record are considered, however, the record is dismal. Nearly every major Army program in the past 20 years has ended in termination. Army leaders now hope to change that record.

Just as the Army’s manpower and budget have changed, so, too, has its posture. In 1985, the Army had over one-third of its forces permanently stationed overseas. Today that number is around 10 percent.

Efforts to plan and execute successful modernization should be informed by prior Army initiatives. Some efforts launched to great fanfare ultimately fell short. Others that were fortunate enough to take place outside major conflict and budget drawdowns, and that were patiently led and shepherded through many obstacles, succeeded. The development of AirLand Battle doctrine, Force XXI capabilities, Stryker Brigade Combat Teams, and Task Force Modularity features prominently among the successful efforts to modernize and adapt the Army. Each of those efforts featured the Chief of Staff of the Army in a key role—either leading the change or supporting and delegating the essential authority—to make it successful.

Army modernization must also be guided by anticipated future environment, threats, technology, and allied capabilities. Global environmental and demographic conditions will contribute to an increased possibility of conflict. The variability of threats and conflict environments leads to a need for a balanced and sufficiently large Army comprised of armored, light- and medium-weight forces (forward-postured where possible and, for those not forward, packaged for expeditionary operations). Russia and China appropriately serve to “anchor” the upper range of the potential threats the U.S. Army could face, but despite the attractiveness of doing so, the service cannot solely focus on those threats to the exclusion of others. To do so would repeat the mistakes of the past. The Army should not misconstrue the guidance on China and Russia as the “principal priorities,” but should remain ready for other conflicts.

Despite the inherent hazards associated with forecasting, the Army has no choice but to make bets. When dealing with a 1-million-person organization, equipping, training, and leader development typically take at least a decade to make any substantive change. The Army must therefore make bets now to remain a preeminent land power. The world of 2019 is a far different place from 2012—and it will likely change multiple times again by 2030, the horizon for this paper.

Implications for the U.S. Army

Attention must be paid to the techniques and methods to manage change in the Army. Continuity of leaders, intellectual preparation of leaders, and the designation of change agents have all proven essential to the success of prior modernization efforts.

Concept. Driving the effort is the Army’s new warfighting concept, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations, published in December 2018. It proposes the central problem to be solved is layered standoff—the array of systems and techniques employed by an adversary to keep U.S. forces at a distance. This concept contains fresh thinking on how to solve the problem by penetrating and disintegrating enemy anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) zones. Complicating development of the concept is the need to focus on multiple adversaries with capabilities and doctrine that are roughly similar today but promise to diverge over time. Authors of the concept propose that solving the layered standoff problem results in the defeat of the adversary, but that premise seems tenuous. Broadening the problem to include the subsequent defeat of enemy forces seems like the answer.

A further challenge for the concept is that it contains the vulnerability that it is dependent on the embrace and support of organizations outside the control of the Army, to wit, the other Services, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). Without their support, MDO will fail.

Experimentation. The Army has created an organization to experiment with the new concept and equipment. But with the demise of Joint Forces Command, conducting large-scale joint experimentation is difficult and subject to service bias. Army experimentation must be continuous and robust.

Manpower. By all measures, the Army is too small for its current missions. It must grow to a size sufficient for it to be able to accomplish the National Defense Strategy at less than high risk and, simultaneously, must take action to reduce manpower in non-essential areas and constrain costs.

Materiel. The Army has identified modernized equipment as a key objective and established six materiel priorities. These priorities are very useful for decision making. The priorities should be based on an evaluation of current versus required capabilities, assessed against the capability’s overall criticality to success, all tied to a future aim point, 2030, by a force employing MDO doctrine. When these priorities are viewed through this lens, questions emerge. The Army should consider according a higher priority to the network and a lesser priority to future vertical lift, based on the author’s assessment.

Most envisioned Army programs are well-conceived; however, this paper makes recommendations regarding hypersonic missiles, long-range strategic cannons, anti-ship cruise missiles, combat vehicles, and other systems for the Army’s consideration. The Army must be constantly on guard to resist the urge to invest in technologies that do not directly contribute to a problem identified in the MDO concept.

The Army acknowledges that as it modernizes materiel, it must also adapt organizations. Army efforts to rethink the echelonment of capabilities, to a degree reversing years of building a brigade-centric force, are sound. The Army should reduce its over-investment in infantry brigade combat teams in favor of more armor brigade combat teams and other capabilities. The Army should reconsider the allocation of unit types and quantities among all three of its components and design the force that best reduces risk in the execution of the NDS.

Finally, recognizing that changing force posture is a difficult proposition, the Army should advocate to permanently forward station more combat forces in Eastern Europe and Southwest Asia.

Rather than seeking to match and exceed each of our adversary’s investments, the Army must focus on enabling its own operational concepts and seeking answers to tough operational and tactical problems. Given the quality of the soldiers and leaders we see on display in Iraq, Afghanistan, South Korea, and 137 other countries around the globe, the Army will, as it has throughout our nation’s history, succeed.

Introduction

Making predictions about the future is both hard and hazardous, but nonetheless necessary. Nine years ago, a senior Army officer stated: “The Army will not face the threat of attack from the air in the foreseeable future.”REF

This confidently made prediction led to the Army’s cancellation of its Surface Launched Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (SLAMRAAM) program, designed to fill a range gap between Stinger missiles and the Patriot system.REF Today, in 2019, air defense in this range represents a major capability gap for the Army.

As the SLAMRAAM example suggests, good people, trying their best, made the decision based on a then-reasonable prediction about the future. They just happened to be wrong. Since World War II the U.S. Army has strived to transform and adapt to meet the challenges of anticipated adversaries, technologies, and environments—with mixed success. As the Army embarks on another ambitious effort to modernize itself, this time for great power competition, how should it proceed? What investments and changes should it make? How can it learn from the past, recognizing the trail is littered with unsuccessful efforts?

The task for the Army is no less than to develop a force capable of deterring and defeating aggression by China and Russia, while also remaining prepared to deal with other regional adversaries (Iraq and North Korea), violent extremist organizations, and other unforeseen challenges.REF The Army lacks the certainty of a single principal competitor (the Soviet Union) and location (NATO) that drove change in the 1980s.

The situation more resembles, as RAND’s Dr. David Johnson has noted, the 1940s, when the United States faced two competitors—Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan—who were peers in their regions.REF As my colleague, Dakota Wood, argues in the introductory paper of this series, this reality calls for new approaches. Consequently, we will advocate for the “U.S. military to shift its thinking from the 20-year lead approach—in constant pursuit of the next transformative moment—to a more iterative and evolutionary approach.”REF Specifically, we advocate for the Army to avoid technological overreach and development of elaborate multi-element programs in favor of programs that are achievable and solve a problem identified in its operational concept.

A good example of a program that followed these tenets would be the M1 tank. Its turbine engine, associated dash speed, stabilized gun system, and Chobham armor enabled the Army to successfully execute its AirLand Battle doctrine, giving Army units the ability to conduct rapid maneuvers on an extended battlefield.REF

A central theme of this paper is to caution the Army against the emergence of “groupthink,” the phenomena that occurs when subordinates mimic the thinking of their superiors.REF Ask anyone why the Army’s Future Combat System (FCS) failed spectacularly, and most of the answers you get will revolve around unrealistic requirements underpinned by overly ambitious technological goals. Official after-action reports reinforce that belief.REF Less well described is how the Army and its leaders internally failed to recognize and deal with growing problems with the FCS program, starting from its formal initiation in 2003 to its spectacular collapse in 2009. Much of this can be attributed to groupthink—officials, often senior, unwilling or unable to question the status quo.

The same risks exist today. Critical thinking is the antithesis of groupthink and must be encouraged at all levels.REF Army professional journals and forums should be filled with soldiers continually questioning operational concepts, modernization priorities, and supporting modernization programs. Professional dissent should be rewarded, not punished. To their credit, today Army senior leaders are personally invested in modernization and speak often and candidly about Army programs. The downside to such visible commitment is that any critique of these public opinions could be perceived as disloyal. Leaders must therefore actively seek viewpoints from multiple sources and reward critical thinking.

The Rebuilding America’s Military Project

This Special Report is the third in a series from The Heritage Foundation’s Center for National Defense titled The Rebuilding America’s Military Project series that addresses the U.S. military’s efforts to both prepare for future challenges and rebuild a military depleted after years of conflict in the Middle East and ill-advised reductions in both funding and end strength.

The first in the series of papers, Rebuilding America’s Military: Thinking About the Future, published July 24, 2018, provides a framework for how we should think about the future and principles for future planning. Rebuilding America’s Military: The United States Marine Corps, published March 21, 2019, discusses the current status of the U.S. Marine Corps and provides prescriptions for returning the Corps to its focus as a powerful and value-added element of U.S. naval power. This paper, Rebuilding America’s Military: The United States Army, provides context and recommendations on how the U.S. Army should approach planning for future conflicts out to the year 2030.

Land Power and the U.S. Army

Samuel Huntington wrote that a military service must understand its purpose or role in implementing national policy. Without such an understanding, he wrote, the service “becomes purposeless, it wallows about amid a variety of conflicting and confusing goals and ultimately it suffers both physical and moral degeneration.”REF The U.S. Army does not suffer from such a lack of understanding but has in the past suffered from identity crises over its relevance, especially when an existential threat requiring land power was not evident.REF

The Army is the oldest and most senior branch of military. According to law:

[The Army] shall be organized, trained, and equipped primarily for prompt and sustained combat incident to operations on land. It is responsible for the preparation of land forces necessary for the effective prosecution of war except as otherwise assigned and, in accordance with integrated joint mobilization plans, for the expansion of the peacetime components of the Army to meet the needs of war.REF

War can take place in the air, at sea, in space, or now, in cyberspace. But it is typically on land that most wars are ultimately won or lost.REF Because people live on land and because to achieve decision an adversary must realize they have been defeated (less obvious with conflict in other domains), land will typically be the most decisive domain.

T. R. Fehrenbach, a veteran of the Korean war and author, perhaps said it best when he wrote:

Americans in 1950 rediscovered something that since Hiroshima they had forgotten: you may fly over a land forever; you may bomb it, atomize it, pulverize it and wipe it clean of life—but if you desire to defend it, protect it, and keep it for civilization, you must do this on the ground, the way the Roman legions did, by putting your young men into the mud.REF

In addition to the attributes that land forces possess to achieve a decision, the presence of land forces signifies a powerful U.S. commitment versus just a presence. The commitment of the U.S. Army “is the most credible signal of U.S. commitment to a nation or region.”REF Such a commitment also contributes to deterrence, specifically deterrence-by-denial, which makes it clear to potential adversaries that they will not succeed in their aggression.

End of Land Warfare?

Beginning at least as early as World War I, individuals have predicted the end of large-scale conventional war on land. Pointing to the horrors of “The Great War” and the Battle of the Somme—which killed over 57,000 British soldiers in one day and 419,000 in four months—a view was advanced that no rational nation or leader would ever again willingly initiate such a disaster.REF Then, in the aftermath of the calamity of World War II, the argument was updated using the idea that the fear of nuclear escalation would essentially prohibit nuclear-equipped nations from ever engaging in large-scale land combat.REF

Later, after the Korean and Vietnam Wars, some suggested that growing global economic interconnectivity between nations would serve to bind nations in such a web of interdependence that it would render war much less attractive and, therefore, impractical. In the years following the end of the Cold War and the 1991 conflict in Iraq, the arguments shifted to a contention that a growing number of democracies in the world, or just a general overall decline in violence over time, would lead to a reduction in inter-state conflict, particularly major land conflict.REF

Similarly, others point out that potential future adversaries have closely observed the superior manner in which the United States goes to war and would thus never choose to contest American interests on land in conventional conflict, but would instead launch devastating cyber, electronic warfare, space, and disinformation campaigns. These critics propose that future wars will now be exclusively fought in the ambiguity of the “gray zone” and that the U.S. should consequently reduce its holdings in conventional land forces in favor of these “soft power” capabilities.REF

Indeed, investment in some of these capabilities is probably warranted, but completely absent in those arguments is the understanding that potential adversaries have opted not to contest America’s military forces on land solely because of the extraordinary dominance that the U.S. has displayed, and that such superiority is not our birthright. If the U.S. wishes to continue to deter large conventional ground combat and keep conflict in the “gray zone,” it requires a continued investment in those capabilities and the capacity to ensure any potential adversary is adequately deterred.

Despite the optimism that sporadically breaks out, it seems clear that for the foreseeable future, America will need a strong army, capable of deterring and defeating both near-peer competitors and regional adversaries. As Dr. Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution summarized, “We may not have an interest in large scale ground combat, but it has an interest in us. Put differently, in contemplating the character and scale of future warfare, the enemy gets a vote too.”REF

Joint Concepts and National Defense Strategies Since 2010

To accomplish its proper role in the joint force and properly plan for the future, the Army must respond to both joint concepts and defense strategies and guidance. The 2017 National Defense Authorization Act made welcome changes to portions of the Department of Defense’s (DOD’s) strategy development process by replacing what had become a relatively useless Quadrennial Defense Review exercise with a true National Defense Strategy.

Although it has been superseded, where the Army stands today is a partial reflection of the 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance. Despite being released only seven years ago, it reflects a series of assumptions that now appear flawed, emphasizing the hazards of predicting the future. The guidance emphasized “smaller, leaner…and technologically advanced forces.” The guidance judged the U.S. relationship with Russia as “important” and called for the U.S. “to build a closer relationship.” The document also declared the end of the war in Iraq and did not anticipate the rise of the Islamic State. China was assessed to be interested in “building a cooperative bilateral relationship” based on a mutual desire for “peace and stability in East Asia.” Counterterrorism and Irregular Warfare were at the top of the list of the Joint Force’s missions.REF

This guidance drove cuts to the Army by moving the DOD’s force-sizing construct away from a two-war construct and by directing that forces not be sized to account for stability operations. The guidance put the Army on a drawdown path to a Regular Army component size of 450,000—a trajectory not changed until the election of President Donald Trump. Force sizing is a task best done gradually, so reversing course and then growing the Army is not easy.

By contrast, two major joint concepts written around the same time seem prescient today. The Joint Operational Access Concept and the Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, both published in 2012, emphasized the need for increased joint integration and the synergy to be derived therein. The concepts described the complementary versus additive employment of capabilities in different domains, particularly important in light of the growing recognition of cyber and space as warfighting domains.REF These documents contain the seeds of the Army’s Multi-Domain Operations concept. The military now needs an updated Joint Operating Concept; much has changed since 2012.

The publication of the 2018 National Defense Strategy signaled a major shift. In a clean break with earlier optimism, China was assessed as seeking “Indo–Pacific regional hegemony,” while Russia desires to “shatter the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and change European and Middle East security and economic structures to its favor.” China and Russia are designated the “principal priorities” for the DOD. The strategy calls for modernization of key capabilities of significance for the Army, among them “forward force maneuver and posture resilience,” missile defense, and “joint lethality in contested environments.”REF The new strategy currently enjoys broad acceptance, including from the bipartisan congressionally chartered commission tasked with evaluating the strategy, which pronounced it “constructive.”REF

Overview of Today’s Army

The Army provides the nation with the capability to conduct sustained land combat. Although it maintains a number of capabilities, for example, missile defense and theater-opening capabilities, its chief value to the nation is its ability to defeat and destroy enemy land forces in battle.

The Army, more so than any service, felt the impact of years of counterinsurgency (COIN) operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Army organizational structure, modernization programs, doctrine, and training were all significantly modified to better enable success in COIN operations. Modernization programs, such as air defense systems not viewed as complementary to COIN operations, were terminated. Brigade and division capabilities were reduced and re-aligned to facilitate COIN warfare. Combat Training Center rotations almost exclusively focused on stability scenarios. Leaders and soldiers often went for years without practicing their core combat tasks, such as counterbattery fire or tank gunnery. As is often the case, when the Army sets its mind to do something, it does it completely and without reservation. Such was the Army’s adaptation to COIN operations. This trait can be extraordinarily powerful, but making long-term decisions based on current conflicts is risky. In hindsight, operations from 2003 to 2015 were not a useful basis to make decisions about future Army programs and structures.

Today the Army is shifting in accordance with national direction to focus on great power competition. Characteristically, the Army is “all in.” Combat Training Center scenarios now focus nearly exclusively on high-end decisive action. New materiel programs, like longer-range artillery with utility in near-peer competitor situations, are being initiated, and organizational structures are being re-examined. Warfighting concepts and doctrine are also shifting to this new construct.

This is all appropriate, but unlike in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, when the 1976 version of the Army’s primary doctrinal manual contained absolutely no mention of COIN operations, the Army has thus far seen fit to preserve some capabilities like Security Force Assistance Brigades, counter drone equipment, and robust Special Operations capabilities. As it moves to the future, the Army must guard against the pendulum swinging too far in the new direction of great power competition and should maintain critical capabilities for COIN and stability operations, including the supporting intellectual underpinnings.

Regarding the Army’s experience with COIN, Dr. David Johnson quoted historian Russell Weigley, who wrote: “Whenever after the Revolution the American army had to conduct a counterguerrilla campaign—in the Second Seminole War of 1835–1842, the Filipino Insurrection of 1899–1903, and in Vietnam in 1965–1973—it found itself almost without an institutional memory of such experiences, had to relearn appropriate tactics at exorbitant costs, and yet tended after each episode to regard it as an aberration that need not be repeated.”REF The Army should heed this warning.

Resources. Budget cuts from the 2011 Budget Control Act and end-strength reductions based on the 2012 Defense Planning Guidance and 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review badly wounded the Army. By 2016, Regular Army end strength was dropping precipitously toward a point potentially as low as 420,000 (with some predicting 350,000)—the lowest the Army had seen since 1939. Readiness among Army units was poor, with as many as two-thirds of Army brigades not ready for combat and readiness being managed solely with the objective to ensure next deploying units were ready—but with associated severe impacts on others.REF In 2017, the Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, General Daniel Allyn, testified that the Army was “outranged, outgunned and outdated.”REF

The budget and end-strength increases provided by the Trump Administration starting in 2017 have had an unquestionably salutary impact. The Administration has requested a total of $182 billion for the Army in 2020, compared to its appropriated 2015 budget of $151 billion, a sizable increase of 20 percent. End strength is re-growing, albeit slowly, with the Army requesting a Regular Army size of 480,000 in 2020.REF In March 2019, General Mark Milley, Army Chief of Staff, reported that 90 percent of brigade combat teams were “ready.”REF

These welcome budget increases, however, mask a pernicious issue in the overall defense budget. Defense costs are growing much faster than inflation. As defense budget expert Todd Harrison identifies, the defense budget proposed for 2019 was 82 percent higher in real terms than it was at the end of the Cold War in 1998, but the size of the military force is 9 percent smaller. Military and civilian labor costs have grown in the past 20 years at 64 percent and 31 percent, respectively, over inflation. Operations and Maintenance accounts have grown at an average of 3.4 percent above inflation over the same time period.REF Bringing these costs in line with inflation seems unattainable, so the reality will be that defense budgets, to even maintain constant buying power, must grow at a rate greater than inflation.

Organization. The Brigade Combat Team (BCT) is the basic combined arms building block of the Army. Divisions normally include two to five BCTs.REF Numerous other combat capabilities, including engineers, military police, and sustainment also exist that allow the Army to accomplish its full range of missions. Roughly one-third of the Army is comprised of combat forces, with the other two-thirds performing institutional, training, and other missions.REF

In 2020, the Army has requested authority for the number of formations shown in Table 1.

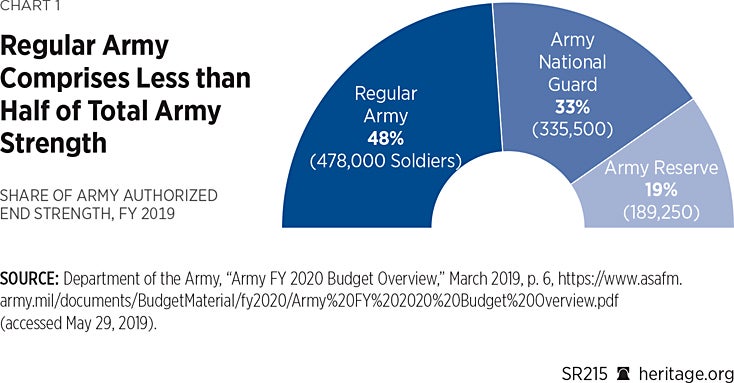

As shown in Chart 1, the Army is unique in the size of, and reliance on, reserve components. Capabilities are divided among the Army Reserve, the Army National Guard, and the Regular Army, with all combat arms found in either the National Guard or the Regular Army. The full-time force, the Regular Army, costs the most, but is able to maintain the highest levels of readiness. The part-time forces, Reserve and National Guard, cost less and are typically not able to achieve as high a level of readiness, especially as the echelon level or complexity of tasks increase.

Optimally, the distribution of units among the three components would be based on the need to execute the defense strategy at the lowest level of risk. Often, however, such a rational decision-making approach has fallen victim to politics or other external factors. National Guard division headquarters, for example, are typically maintained in excess of Army requirements but are difficult to reduce due to external pressures.REF

Additionally, when deciding which capabilities should be in the three Army components, there is a widely held belief that General Creighton Abrams, Army Chief of Staff from 1972 to 1974, directed that critical logistical elements be placed in the Reserve to ensure that future American Presidents would be required to mobilize the Reserve to conduct any sort of significant ground war—and thus involve the American people.REF Whether or not there was such a policy, today it would be difficult to send the Army to war without immediately mobilizing elements of the Reserve. Relations between the Regular Army and the National Guard have, at times, been strained, particularly when resources become scarce. Today, relationships between the components are close, based primarily on outreach by Army leaders.

Army Manpower. Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution points out that America has balanced between “dueling paradigms in sizing its ground forces.” On the one hand, it has a romanticized version of a citizen–soldier coming to the aid of his country, and then when the conflict is over, returning to his peacetime profession. This image fits neatly with the Founding Father’s distrust of large standing armies. The contrasting view emerged post–World War II with the U.S. convinced it must remain engaged in the world with a large professional army.REF Strength levels have thus fluctuated from 165,000 Regular Army soldiers in 1938 to over 8 million in 1945. Since then, the Army has been on a generally downward trajectory to where it stands today at approximately 478,000, with 480,000 requested for FY 2020. (See Chart 2.)

Manpower is costly, the most expensive single element in the Army budget. In an effort to find savings, the Obama Administration began to sharply reduce the size of the Army, from 562,000 in 2012 to 475,000 in 2016, with announced intent to go to 450,000 in 2018—and perhaps lower still.REF As already noted, the supporting rational for the reductions, the revised Defense Planning Guidance in 2012, stated, “U.S. forces will no longer be sized to conduct large-scale, prolonged stability operations.” It also altered the DOD’s force construct to include a more modest requirement to defeat a potential adversary as well as “denying the objectives of—or imposing unacceptable costs on—an opportunistic aggressor in a second region.”REF

Army leaders are on record consistently expressing the need for a bigger Army. General Milley has stated that he believes the Regular Army should number between 540,000 and 550,000; the National Guard from 350,000 to 355,000; and the Reserve between 205,000 and 209,000.REF He has further clarified this assessment to say that levels below these numbers represent “high” risk.

The Army had hoped to restore its Regular Army end strength quickly back to a level over 500,000 but in 2018 experienced difficulties meeting its recruiting goals, falling short by 6,500 volunteers (although in the process recruiting 70,000 individuals, the most in 10 years).

Army Equipping. With the exception of the Stryker vehicle and unmanned aerial vehicles, the Army is currently depending on equipment largely delivered in the 1980s and incrementally improved since. From 2002 through 2014, for a variety of reasons, nearly every major Army modernization program was terminated. These include the Crusader artillery system in 2002, the Comanche helicopter in 2004, Aerial Common Sensor aircraft in 2006, the Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter in 2008, the Future Combat Systems in 2009, and the Ground Combat Vehicle in 2014.REF Each system suffered from its own challenges, but in general, the programs either experienced funding cuts, were overly ambitious, key leaders changed and consequently so did the priorities, or the requirements changed in mid-stride.

The only “new-design” Army major equipment program currently in the procurement stage is the Joint Lightweight Tactical Vehicle (JLTV), but the Army has recently initiated multiple research and development programs with the aspiration to begin procurement as early as the mid-2020s.

In an effort to achieve better modernization outcomes, the Army activated a new four-star command Army Futures Command (AFC) reaching full operating capability in July 2019. Army modernization currently commands the attention of senior leaders, and they are devoting a great deal of time to overseeing programs and reviewing requirements. Six modernization priorities have been established and eight cross-functional teams created to manage requirements and programs.REF

Army Posture. The 2018 National Defense Strategy calls out the need to “[d]evelop a lethal, agile, and resilient force posture and employment” as a key means to “build a more lethal force.”REF In the past 20 years, the Army has primarily become a U.S.-based expeditionary force. In 1985, 36 percent of the Army was stationed overseas; today that figure is 10 percent.REF The desire to find a peace dividend following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, combined with the reluctance to close bases in the United States, led to large-scale base closure overseas. The Secretary of Defense’s Integrated Global Posture and Basing Study (IGPBS), completed in 2004, directed the removal of heavy forces from Europe, a leaner command and support structure in Europe, a reliance on rotational forces, and a reduction in forces in South Korea.REF

Continuing this trend, in 2015 the Army shifted from a forward-stationed Brigade Combat Team on the Korean Peninsula to a rotational unit. In 2017, on the heels of Russian aggression in the Ukraine, U.S.-stationed armor BCTs began a continuous “heel-to-toe” rotation to Europe to enhance deterrence and warfighting capability and to compensate for the fact that there were no longer any heavy U.S. Army forces in Europe.REF Thus far, the Army’s position has been that rotational BCTs provide a trained and ready unit, and consequently higher readiness, than a forward-stationed unit faced with frequent personnel transition. Critics of the rotational model argue that forward-stationed units provide more deterrent value, allow units to become more familiar with the environment, and are less costly (if rotational units deploy with their equipment).REF

Fifteen years later, the United States faces a vastly different geopolitical situation from what was considered in the DOD’s 2004 IGPBS. Yet, unlike other choices like equipment, reversing decisions concerning basing and real estate are much more difficult. Current Army overseas presence is a sobering reminder of the consequences of making decisions with long-lasting consequences during periods of strategic uncertainty.

Army Adaptation Since World War II

The Army possesses a mixed history of adaptation to threats and environment since World War II. Changing an institution the size of the U.S. Army is no small undertaking and requires a combination of clear vision, ruthless execution, and steely resolve. Certainly, as important as those other factors, change requires luck. The best-conceived plan to change the Army can be derailed by an unforeseen conflict requiring the commitment of the entire institution to succeed or an unexpected reduction in funding. Fundamental change usually requires a relatively stable period when it is possible to step back and consider the environment and threats. Change in the midst of war is possible, for example the introduction of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) in Vietnam in 1965 or the reorganization into modular Brigade Combat Teams via Task Force Modularity from 2003 to 2005, but such examples are rare and normally more tactical in nature.REF To actually implement across-the-board change also requires resources, typically more than are available in the midst of a drawdown, something the Army undergoes with regularity.

Concepts Versus Doctrine. The Army prides itself on being driven by warfighting concepts that “establish the intellectual foundation for Army modernization and help Army leaders identify opportunities to improve future force capabilities.”REF Doctrine, on the other hand, guides current operations. While different, the terms are often mistakenly used interchangeably. A concept is typically not executable today and is focused on the future, while doctrine must be executable today, i.e., to “fight tonight.”

Army change has not always been driven by an official concept referred to as such, but to be successful, the change agent(s) should have a “sense of a problem to be solved, the components of the solution to that problem, and the interaction of those components in solving the problem.”REF This type of thinking normally only results from close reflective study of a wide spectrum of technology, threat, history, world settings, and trends.

Change can come as a result of external pressure, internal leadership from an Army Chief of Staff or other senior leader, or, occasionally, from a more junior, but determined, group of advocates.

What follows summarizes major Army change efforts since World War II, recognizing that each of these can and has been the topic of individual monographs.

The Louisiana Maneuvers. Through World War II and the Korean War, Army doctrine and organization largely only changed to meet near-term wartime needs. Chief of Staff General George Marshall (1939–1946) directed the 1941 General Headquarters Maneuvers (also known as the Louisiana Maneuvers) featuring over 400,000 soldiers in multiple states. Most of the insights were gained in training and leadership, but from these exercises erroneous lessons influenced tank employment and organization in ways that did not account for German capabilities.REF

The Atomic Age. General Maxwell Taylor (Chief: 1955–1959) was essentially coerced by the Eisenhower Administration to adapt the Army to the requirements of the atomic battlefield or risk irrelevance. The Army’s response to the nuclear age was the Pentomic Division. The division included five battle groups and was a reaction to Eisenhower’s “Era of Massive Retaliation” and New Look policies.REF The ostensible purpose was to survive a nuclear attack and successfully employ tactical nuclear weapons. However, history has been unkind in its assessment of this effort, to wit: “[I]n its attempt to market itself to regain relevance in the nation’s security planning, the Army dangerously lost its focus, leading to rushed force designs and incomplete testing and wargaming throughout the Pentomic division’s development.”REF

The “ROAD” Back. In 1961 General Taylor, by now Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, urged the reorganization of the Army to “meet the challenge of the international power struggle.”REF The Army regained its intellectual footing and a true conventional warfighting capability with the introduction of the Reorganization Objectives Army Division (ROAD) concept in 1961, representing a return to the triangular (three brigade) division structures of World War II and the Korean War.REF The division structure better supported the Kennedy Administration’s new national strategy of “Flexible Response.”REF

Vietnam. The Army’s commitment in Vietnam caused it to dramatically expand in size and to develop capabilities such as Special Forces. Some, such as Andrew Krepinevich, argued that a rigid organizational culture limited the Army’s ability to fully adapt to the demands of the Vietnam War because it preferred to focus on conventional versus counterinsurgency tactics.REF Others point to great adaptation on the tactical level. On a positive note, as a result of 1962 direction from Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to take a “bold new look at land warfare mobility” and to do so “in an atmosphere divorced from traditional viewpoints and past policies,” the Army embarked on a path that resulted in the creation of the Airmobile division. In 1965, after a number of tests and refinements, the Army deployed the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) to Vietnam, where it met with success.REF

Post-Vietnam. General William Westmoreland became the Chief of Staff in July 1968 and used the last three years of his four-year tour to focus on rebuilding the post-Vietnam Army. Perhaps the greatest challenge he tackled was to move the Army to an all-volunteer force and restore professionalism to the Army. Only with hindsight do we see the significance of his direction to restructure Continental Army and Combat Development Commands into the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) and Forces Command.REF

The Activation of TRADOC. TRADOC, activated in 1973 by General Creighton Abrams (Chief from 1972–1974), played a key role in all subsequent Army change. Its first two commanders, General William DePuy and Donn Starry, were brilliant, energetic, and active leaders. While the Army had been engaged in Vietnam, the Soviets had modernized families of weapons, tanks, and artillery in particular, all part of a new operational level doctrine they referred to as “Mass, Momentum, and Continuous Land Combat,” with the objective to overwhelm NATO defenses.REF Observations from the October 1973 Yom Kippur War also helped crystalize assessments of Soviet tactics and their modernized equipment. This confluence of events led TRADOC under DuPuy to publish the 1976 edition of “FM [Field Manual] 100–5, Operations”REF describing a new doctrine termed “Active Defense.” Active Defense, however, never met widespread acceptance for a variety of reasons: It lacked wide scale “buy-in” from the Army and its leaders; it expressed a counter-cultural preference for the defense over the offense; and, almost immediately, it began to appear inadequate to meet the Soviet challenge.REF But “Active Defense” and the thinking behind it helped make possible the concept and doctrine that followed.

AirLand Battle. AirLand Battle has come to epitomize a successful effort to change the Army. AirLand Battle represents a widely accepted positive example of Army success in concept and capability development, supported by honest operational experiments, helping to evolve Active Defense to two versions of AirLand Battle. The Army was aided in its efforts by having a monolithic, clearly understood threat in a defined geographic area, with little potential for another existential threat to appear in the short to mid-term, upon which to base its concepts.

General Donn Starry assumed command of TRADOC on July 1, 1977. Coming from command of V Corps in Europe, Starry employed his personal vision of battle in Europe, which he referred to as “The Central Battle,” to frame the problem. Starry employed new analytic tools, such as the “Battlefield Development Plan,” to describe the adversary, his tactics, the terrain, and proposed solutions to the problem. The derived solution was to “so control and moderate the force ratios at the FLOT (Forward Line of Troops) that it is possible to seize the initiative by maneuvering forces to defeat the enemy.”REF The effort culminated in the 1982 version of “FM 100–5, Operations” describing a new AirLand Battle doctrine.REF

Starry deliberately cast a wider net than his predecessor to receive input and write the new doctrine. Consequently, unlike the 1976 version, the 1982 version received widespread acceptance and formed the basis for a decade-long partnership with the U.S. Air Force. This partnership included the agreement between the Chiefs of Staff Army and Air Force on 31 initiatives to help improve joint warfighting capability. The doctrine articulated specific roles for corps, divisions, and brigades. AirLand Battle also drove modernization efforts, including the development of the Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System and the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS). REF

Reflecting on the effort, Starry later wrote, “That kind of thinking can only be done by imaginative people who have trained themselves or have been trained to think logically about tough problems.”REF Starry himself was well-prepared for this role by virtue of multiple assignments in the Pentagon in resource management and force structure and, most significantly, as the commander of Fort Knox, Kentucky, and the Armor School.REF Starry also noted that for change to be successful, there must be:

- An institution or mechanism to identify the need for change;

- A spokesman for change, who must build a consensus;

- Continuity among the architects of change; and

- Rigorous trials to test proposed changes.REF

Force XXI. Operation Desert Storm in 1991 proved the value of many of the Army’s prior modernization efforts. Following the war, and the December 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, General Gordon Sullivan (1991–1995) realized that what had served the Army so well in Desert Storm might not be adequate for seemingly indeterminate future battlefields. In 1992, Sullivan established a Louisiana Maneuvers Task Force to focus on testing modern technologies and organizations to win in multiple-theater fights. The problem was divided into three pieces: The branch schools “owned” the current force; a Force XXI campaign tested new and emerging technologies and considered the near-mid futures; and Sullivan’s successor, General Dennis Reimer, established the Army After Next study to look as far as 30 years into the future.REF

First Brigade, 4th Infantry Division was designated as a “Task Force XXI” for experimentation. Some of the results that flowed from Force XXI were the Total Asset Visibility program, Battlefield Digitization, and “Owning the Night.” Over half the programs tested later became programs of record, including Enhanced Position Location Reporting System, Blue Force Tracking, and Force XXI Battle Command Brigade and Below.REF Like Starry, Sullivan had been well prepared by institutional assignments to take on the challenge of changing the Army. In addition to his operational assignments, he had served as the Assistant Commandant of the Armor School, Deputy Commandant of the Command and General Staff College, the Army G-3, and the Vice Chief of Staff of the Army.REF

Army Transformation. In 1999, General Eric Shinseki (1999–2003) announced a campaign of “Army Transformation” with three distinct efforts: a trained and ready Legacy force, an Interim Force, and an Objective Force. Like some of his predecessors, Shinseki had been well-prepared to take on Army change through his assignments as Army G-3 and the Army Vice Chief of Staff.REF Army Transformation ultimately met with mixed results. The terror attacks of September 11, 2001, and the resulting overseas COIN operations complicated the Army’s ability to focus on transformation. Nevertheless, the Interim Force quickly took the form of Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (SBCT) and was conceived and fielded in a remarkably short amount of time, helped by the fact that the Stryker was an off-the-shelf platform. The first Stryker Brigade deployed to Iraq in December 2003, providing combat commanders additional capability only 18 months after being fielded.REF The transformative impact of the Stryker Brigades, with their unprecedented mobility and powerful network capability based on Force XXI technology, was under-appreciated. The Objective Force was to be equipped by the Future Combat Systems but ultimately failed for a variety of reasons, including overly ambitious technology aspirations, vulnerable assumptions on the character of future combat, cost control, resistance both internal and external to the Army, and a perceived irrelevance against the backdrop of COIN operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In 2009, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates terminated the Future Combat Systems (FCS), the largest and most ambitious acquisition program in the Army’s history, after the Army had spent at least $19 billion.REF The Army Transformation Campaign Plan was initially well-supported and artfully designed. The effort had been disaggregated into manageable chunks and was well understood. But FCS, in addition to the many issues documented in official after-action reports, further suffered from lack of attention by Army senior leadership, who were distracted by pressing overseas conflicts, and, as earlier mentioned, the active presence of groupthink, which prevented earlier identification of program shortfalls. However, many of the technologies matured under the FCS program (e.g., active protection) survived and were incorporated in future Army programs.

Adaptation for Iraq and Afghanistan. Faced with the pressing demand for deployed forces, General Peter Schoomaker (2003–2007) created Task Force Modularity, which operated between 2003 and 2005 to transform the Army from a division-based to a brigade-based force. Becoming more modular had been an Army objective since at least 1994, but the wars gave the task much more urgency.REF The Army modularized its BCTs in very short order. The Task Force planned to look at echelons above Brigade, but the effort stopped before that could occur. Adjustments have since been made to the design of the modular BCT, in some cases returning capabilities that were removed, such as engineer battalions, but the basics have remained intact. Often overlooked during this period were the incredible efforts of the Army modernization community to equip forces for COIN operations. Countless improvements were made in body armor, weapons optics, unmanned aerial vehicles, counter-improvised explosive device equipment, and persistent surveillance. Because these systems were often conceived outside normal acquisition programs, they have not received the recognition they deserve.

Post-FCS. Regrouping after the cancellation of FCS, in 2010 the Army designated the 2nd Brigade Combat Team of the 1st Armored Division as an experimental unit. But by 2016, due to operational requirements, Army leadership was forced to return the brigade to Forces Command for rotational deployments, leaving the Army without a dedicated force to conduct experimentation—highlighting the challenges of attempting change while decisively engaged.

Awakening to Great Power Competition. Growing concern over Russian actions in Georgia in 2008, crystalized by the Russian invasion of the Ukraine in 2014, as well as Chinese actions in the South China Sea from 2014 to 2015, led Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work to give a 2015 speech suggesting the Army needed to get to work quickly on an “AirLand Power 2.0,” referring to the earlier groundbreaking work on AirLand Battle.REF This wake-up call precipitated work on the concept that evolved into the Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) concept.

Multi-Domain Operations. The prior Army operating concept, “Win in a Complex World,” published in October 2014, attempted to describe how the Army would operate in a future that was both “unknown and unknowable.”REF The concept, developed in an abbreviated time frame, did not enjoy the advantage of being narrowed in scope by a NDS and had little impact on influencing the course of Army modernization. Four years later, in December 2018, the Army published Multi-Domain Operations.REF It benefited from lessons gleaned by Army officers from their visits to the Ukraine analyzing the battles between Russian-backed forces and Ukrainians from 2014 to 2015.

Several key aspects distinguish MDO from prior thinking. The first is the increased emphasis on warfighting domain integration versus simply synchronization or coordination. MDO requires leaders to employ other domains to achieve specified freedom of action. The second aspect is the notion that competition is the norm, and that nations compete, fight, and return to competition. Finally, MDO narrowly focuses on the problem of layered standoff and proposes the tenets of calibrated force presence, multi-domain formations, and convergence to deal with the challenges identified in the NDS. Close examination reveals that MDO is not, as some allege, “old wine in a new bottle.” It proposes new solutions to new problems.REF It is too early to determine whether it will ultimately be successful in driving Army change.

Summary. Change in a 1-million-person organization is difficult under the best of circumstances. Nevertheless, there have been clear successes in post–World War II Army efforts to modernize in response to strategic challenges. AirLand Battle doctrine, Force XXI capabilities, Stryker Brigade Combat Teams, and Task Force Modularity feature prominently among these. History suggests that it is difficult to fundamentally change the Army when it is decisively engaged in conflict or if funding is decreasing precipitously.

Leadership is the fundamental ingredient needed to successfully change the Army. Over time the importance of the role of the Army Chief of Staff as a change agent, more than any other individual, becomes clear. For change to be successful, the Chief must either lead it or zealously support it. In the case of AirLand Battle, General Donn Starry had vision, and General Edward “Shy” Meyer (1979–1983) delegated the necessary authority to Starry to allow success. Army history suggests that efforts will be more successful if the chief architect (often, but not always, the Chief of Staff) has been well-prepared for the task through multiple institutional assignments.

In the past, interwar periods gave the Army opportunity to pause and think. That does not seem to be an option today. It appears the Army must now continue to support overseas operations and undergo change at the same time.REF

Environments and Threats: The Changing Strategic and Operational Context

Certain assumptions must be made to enable planning for the future. Army efforts to modernize must consider external factors such as demographics, potential adversaries, technology, and other key areas.

Environment. The global environment plays a role in the frequency, type, and location of future conflict involving Army forces. Resource scarcity, driven by an ever-increasing world population and slowly depleting natural resources (e.g., forests and water), will contribute to increased friction and the potential for conflict involving the U.S. Army. Climate change will displace coastal populations, potentially leading to strife. The world’s population is expected to reach 9.9 billion by 2050, up from 7.6 billion today.REF

Concurrently, urbanization is expected to increase. Today there are 31 megacities with at least 10 million inhabitants; by 2030 the U.N. expects the number to grow to 41.REF Witnessing the fights in Mosul, Raqqa, and Baghdad, the U.S. Army fully expects to have to fight in dense urban areas. Chief of Staff General Mark Milley predicted: “[W]e have to adapt the American way of war to the unique reality of future combat in highly dense urban areas.”REF Critics, on the other hand, question whether the Army could ever hope to be successful in such an environment.REF While it is not inevitable that the Army will fight in major cities, recent history, however, suggests that ignoring the challenge of urban conflict is no longer a wise strategy.REF

Clearly, global demographics and other issues can be expected to provide plenty of tinder for violence to spark, but the real cause for concern is the complex geopolitical situation facing the United States. As Michael Morell, former deputy director of the CIA has summarized, “World War II starred more implacable foes. The Cold War was a 40-year existential threat. But never before [speaking of today] have so many global and regional powers, rogue nations and nonstate actors converged in such an interconnected world.”REF

U.S. Defense Spending. The amount of available resources directly influences future Army modernization plans. Unfortunately, U.S. defense spending is acutely pressured by entitlement spending, to the point that the percentage of the federal budget devoted to defense stands at the lowest it has been in decades: 14 percent.REF As recently as 1975, that number was 25 percent. Long-range Congressional Budget Office projections predict that unless America is willing to accept an inexorably growing national debt dwarfing our annual gross domestic product (GDP), reductions in spending and/or increases in revenue as much as 3 percent per year will be needed.REF Legislative solutions to tackling growing entitlement costs have thus far eluded Congress, and there seems to be little willingness to take on these issues. The result is that for the foreseeable future the U.S. military and the Army will operate in a resource-constrained environment with the requirement to make difficult financial choices regarding investments.

Allies and Alliances. The 2018 National Defense Strategy assigns great importance to strengthening alliances, noting they provide a “durable, asymmetric strategic advantage that no competitor or rival can match.”REF Allies also offer critical political legitimacy, access, and overflight permissions. History has proven the value of U.S.-led coalitions in defeating aggression over the past 80 years. Yet the assumption that our allies will be able and willing to play substantial and enduring roles in countering near-peer competitors into the future may no longer be valid.

During the Cold War, Germany’s military, for example, had 5,000 battle tanks; 500,000 personnel; and was spending 3 percent of GDP on defense.REF Today, only half of Germany’s approximately 200 Leopard tanks, 12 of 50 Tiger helicopters, and 39 of 128 Typhoon fighters are considered ready for combat. While committing in 2014 to reach NATO’s goal to spend 2 percent of its GDP on defense by 2024, Germany’s defense spending stands today at 1.24 percent of its GDP, and a viable plan to get to 2 percent is missing in action.REF Germany’s own defense parliamentary commissioner consequently assesses their military as “not deployable for collective defense.”REF While most experts concede the 2 percent GDP defense spending goal is imperfect, none have advanced any meaningful alternative.

Other U.S allies are also experiencing challenges maintaining military power. Some, like Japan, face a demographic problem with a rapidly aging population. In 2017, Japan’s military was only able to recruit 77 percent of its planned intake of male fixed-term personnel, and 37 percent of Japan’s active-duty military is over 40 years old.REF Similarly, Sweden converted to an all-volunteer force in 2010 but, faced with a lack of volunteers, was forced to revert to mandatory service in 2018.REF The Canadian armed forces have nearly been disbanded, save for a few remnants.REF

None of this should suggest that alliances are not critically important or that U.S. efforts to persuade allies of the value of maintaining strong militaries should not continue. Nonetheless, U.S. Army strategies should be based on realistic assumptions concerning future contributions from allies.

Technology. The Army must consider the impact of technology on future war. Speaking on this topic, General Milley makes a distinction between the nature and character of war, saying:

The nature of war never changes; it’s immutable. War is a human function, a behavior that involves emotions, fears, friction, and chance. It’s the imposition of political will on your opponent by the use of violence. The character of war though is how you fight—when, where, and with what weapons. It’s the doctrine, organization, and materiel. The character of war does change, and it changes often. Every time a new technology is introduced, the character of war is changing. But we undergo fundamental shifts in the character of war only once in a while; it doesn’t happen often.REF

Washington, DC, is awash today in predictions that combinations of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics (especially swarms), hypersonic weapons, railguns, and directed-energy weapons will fundamentally change warfare. Less plentiful are the operational concepts that describe how these systems will be used. Great significance is ascribed to the amounts of money that China and Russia are investing in advanced technologies such as hypersonic missiles and AI, while opinion pieces warn daily that the U.S. must “win” the hypersonic missile race.REF Meanwhile, DOD leaders trudge endlessly up Capitol Hill to assure members of Congress that they take these new technologies seriously.

Aspects of these technologies will assuredly change the character of land war, and continued Army exploration of their application is essential. But Army leaders must simultaneously guard against the historic temptation to turn “the latest technological breakthrough to the benefit of short-term institutional goals.”REF Army leaders have, in the past, endeavored to “reverse engineer” the process to find uses to convert technological promise into combat capability. For example, the hypersonic missile “race” need only be “won” if, indeed, a hypersonic missile fills a necessary capability gap for the joint force.

Geopolitical Competition and Threats. The 2018 National Defense Strategy specifies the central problem facing the United States as “the reemergence of long-term, strategic competition by what the National Security Strategy classifies as revisionist powers.”REF It names China and Russia as the two “principal priorities” for the DOD for increased investment, while U.S. forces must continue to deter and counter the rogue regimes of North Korea and Iran.

Russia.Since the August 2008 Russian “five-day war” with Georgia when Russian military limitations were on full display, Moscow embarked on comprehensive reforms to modernize its military. These “New Look” reforms have resulted in smaller, more agile forces able to conduct a full range of military operations.REF Military equipment has been updated with an emphasis on coastal defense cruise missiles, air/surface/sub-launched anti-ship missiles, submarine-launched torpedoes, and naval mines, along with Russian fighter, bomber, and surface-to-air missile capability. Russia has invested effort in developing faster kill chains and has made major investments in integrated aerospace defense systems supporting an A2/AD concept. Ground forces include some 350,000 personnel organized into 40 active and reserve maneuver brigades and eight maneuver divisions.REF

Russia does not have the enormous resources the Soviet Union possessed, and indeed lacks a raw strength advantage over NATO, but instead primarily poses a “time/distance problem for U.S. forces.”REF Most likely future challenges for the U.S. include the Russian launch of a fait accompli attack preceded by “next generation” operations, ultimately presenting NATO with the unappetizing need to forcibly enter and retake an occupied country or large chunk of terrain. To prevent such a situation from developing, the task for the U.S. Army and joint force is to take the threat of the short-win “off the table.”REF Forward-stationed heavy forces; pre-positioned stocks of equipment; robust Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR); engineers; long-range fires; and air defense will be important capabilities in such a scenario. Another alternative scenario would be to fight Russian-equipped or Russian proxy forces in a strategically important region of the world. That scenario requires high-end conventional forces protected by armor and active protection, supported by robust artillery, missiles, and other fires. In these scenarios, the U.S. Army would likely be a net consumer of U.S. joint force capabilities.

China. President Xi Jinping has made the strengthening and modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) a national priority. Significantly, Xi has set three major milestones for the PLA: “becoming a mechanized force with increased informatized and strategic capabilities by 2020, a fully modernized force by 2035, and a worldwide first-class military by midcentury.”REF China uses a phrase “informatized warfare” to refer to the act of gathering and using information to conduct military operations in all military domains and has devoted considerable resources and attention to that area of the military. For the time being, China believes they currently have a “period of strategic opportunity” with no pressing national security challenges in order to conduct their aggressive agenda of modernization and professionalization.

In addition to already strong space/counterspace, cyber, information, and cruise and ballistic missile capabilities, China is investing in a blue-water navy and modernized ground forces. China’s Army is the largest in the world, with 915,000 people on active duty. China describes its military strategy as one of “active defense,” a concept it describes as “strategically defensive but operationally offensive.” Future challenges for the U.S. could include China’s forcible attempts to seize Taiwan or territory in nearby countries such as Vietnam, Japan, the Philippines, or India, or to assist North Korea in an attack on South Korea. Future scenarios such as these would require primarily light- and medium-weight Army forces capable of rapid deployment, able to employ robust air and missile defense systems, ground-launched anti-ship missiles, and long-range fires. Army capabilities in the form of theater opening, logistics, communications, and medical would also be critical. In these scenarios, it is likely the Army would be a net provider of U.S. joint force.

North Korea. Comprising one of the two destabilizing “rogue regimes” of concern described in the NDS, North Korea possesses significant nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons; cyber capabilities; and an Army the size of the U.S. Army, albeit less well-equipped and trained.REF The Korean security situation is complicated by the proximity of the South Korean capital, Seoul, near the border, creating a time–distance requirement to reinforce South Korea quickly. Deterrence and fighting on the Korean peninsula represent one of the most pressing requirements—and perhaps most immediate for U.S. Army forces existing today—with needs for heavy and light BCTs, fires, sustainment, and Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear defense units. Absent a regime change or other negotiated breakthrough, it will remain a focus for the U.S. Army for the foreseeable future.

Iran. The second of the two “rogue regimes” mentioned in the NDS, Iran is the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, notably through its proxies, Hezbollah and Hamas. It has contributed to regional instability in countries like Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. As relates to proxy forces, Israel’s experience in the 2006 Second Lebanese War is instructive. In that conflict Israel faced advanced Iranian-supplied anti-tank missiles, such as the Kornet AT-14, tanks, and thousands of crude ballistic missiles in the hands of Hezbollah fighters.

Today, thanks to Iran, those capabilities have undergone still further improvement.REF In addition to the activities of the Quds Force to reinforce Iranian goals to foment instability within neighboring countries, Iran continues to improve its ballistic missile and air-defense capabilities.REF Likely requirements for U.S. Army forces include the ability to deter, engage, and defeat well-equipped Iranian-backed proxy forces and Quds Force operatives in the Middle East in both conventional and counterinsurgency operations. Both heavy and light BCTs, supported by fires, Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFAB), and ISR will be important U.S. Army capabilities in those scenarios.

Countering Terror and Counterinsurgency. Because COIN capabilities are difficult to regenerate—and based on the likelihood they will be needed—the Army must maintain and improve counterinsurgency capabilities to include supporting friendly partners with advise-and-assist forces, training, and equipment. Army forces must maintain the ability to detect and neutralize terror networks. The Army must maintain the intellectual foundations of its counterinsurgency capabilities.

Summary.Global environmental and demographic conditions will contribute to an increased possibility of conflict. Transitioning from a bi-polar to a uni-polar and multi-polar global-security construct will reduce world-security stability by introducing additional complexity and potential for the creation of new balances of power. Frank Hoffman, who participated in the drafting of the NDS, summarized it thus: “[B]igger enemies, few friends with diminished contributions, and a weakened government that has both less influence and a smaller iron fist behind its diplomacy. This is a more multipolar and chaotic world.”REF

Based on the guidance in the 2018 NDS, Russia and China appropriately serve to “anchor” the upper range of the potential threats the U.S. Army could face, but despite the attractiveness of doing so, the service cannot solely focus on those threats to the exclusion of others. To do so would repeat the mistakes of the past. The guidance that China and Russia are the “principal priorities” does not negate the need for the Army to remain ready for other conflicts. Further, the NDS and the Army in its concepts appropriately acknowledge that conflict is no longer binary—either at war or at peace. Instead, the future security environment will be characterized by constant competition interspersed with highly lethal conflicts. This future has enormous implications for Army force design and posture.

None of this makes the mission of the U.S. Army to prepare for future war easy. Despite a projected 2020 budget of $182 billion, it will not be enough to satisfy all the Army’s requirements: Tough choices will be required. In sum, the future will demand the Army adopt a good “boxing stance” with solid power in each hand, while maintaining the ability to defend if counter-punched.

The variability of threats and conflict environments described above leads to a need for a balanced and sufficiently large Army comprised of armored and light- and medium-weight forces, forward postured where possible and, for those not forward, packaged for expeditionary operations. Differing weight forces account for the potential of conflict in open and restricted terrain. In-place forces deny the enemy the ability to consolidate gains, deny accomplishment of full objectives, and set conditions for force flow from the U.S. This includes degrading enemy A2/AD capabilities.

Highly lethal early arrivals should be equipped with anti-armor, anti-air, and, in the Indo–Pacific, anti-ship capabilities. Armor forces must be protected from advanced anti-armor capabilities using active protection. Early deploying packages must be comprised of pure Regular Army, with reserve components employed for later-arriving requirements, homeland defense, and backfill of Army global presence, institutional, and engagement missions. Army forces must be able to defend themselves from air attack, with the most critical nodes protected from missile attack. Logistics forces sufficient to support combat units until contractor support can be established are also required.

The Russian and North Korean threats drive the need for Army forces with echeloned high-end conventional warfighting capabilities possessing long-range fires and air and missile defense capabilities. The Chinese threat dictates light forces able to operate in complex terrain with sea denial and air and missile defense capabilities, as well as robust theater opening, communications, and common logistics.

Implications for the U.S. Army

How then should the Army plan for the future, given the absolute necessity for modernization coupled with a high degree of future uncertainty and the uneven track record of prior efforts? The Army is off to a good start, but there are many opportunities for the train to jump the tracks.

Forecasting. Some even counsel it is a fool’s errand to make predictions—or indeed even devise a U.S. grand strategy since our record of success in forecasting is so dismal. President Bill Clinton, for example, reportedly admired the actions of Presidents Roosevelt and Truman in dealing with Hitler and Stalin, who “had powerful instincts about what had to be done[,] and they just made it up as they went along.”REF Indeed, one could look at the 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG) and wonder how it completely failed to anticipate events only seven years in the future. National Defense University strategist Dr. Frank Hoffman, evaluating the 2012 DSG wrote: “Every assumption made by the Barack Obama administration and accepted by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and the Pentagon at the time (Russia: benign, China: not assertive; Sunnis: contented) all proved completely wrong.”REF

The Army, however, cannot afford the luxury of waiting until the future is clear before acting. When dealing with a 1-million-person organization, equipping, training, and leader development typically take at least a decade to make any substantive change. The Army must therefore make bets now to remain a preeminent land power. The world of 2019 is a far different place from 2012, and it will likely change multiple times again by 2030—the horizon for this paper. How then to avoid the mistakes of 2012, and, at least in the words of military historian Michael Howard, “avoid getting it terribly wrong?”REF

Historian Lawrence Freedman wrote that “history is a terrific prism through which to see how little the present has to say about the future.” Similarly, Colin Gray said, “Large institutions, including the Armed Forces, tend to think about the future in linear and evolutionary steps and make implicit assumptions about the next war as merely an extension of the last. This results in strategic and operational surprise.”REF With the rapid development of technologies and the movement into a multi-polar world, the next 20 or so years may well prove that idea.

Managing Change. Putting in place the right mechanisms for change is nearly as important for success as the components of the change itself. Prior Army change efforts have highlighted the importance of continuity in leadership, the preparation of leaders to conceive and implement change, the need for consensus-building and outreach, and the organization of the effort itself.

Continuity. General Starry advised there must be “continuity among the architects of change so that consistency of effort is brought to bear on the process.”REF Unfortunately, often Army leaders rotate so quickly that they are not able to form their vision and create irreversible momentum before it is time to leave. Many partially credit the success of the reforms at the Internal Revenue Service that took place between 1997–2002 to the relatively lengthy five-year term of the commissioner, Charles Rossotti, and his ability to see change through to completion.REF A good example of a key position rotated too quickly is the Director of Force Management, a position in the Army Staff responsible for critical force structure decisions. Lately the Army has been rotating officers through the position every 12–18 months, precluding any from developing the deep expertise to advise and lead the critical decision-making processes regarding force structure.