On September 28, 2020, major fighting broke out along the front lines of the decades-old Nagorno–Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Far from being a small skirmish, fighting is taking place along the entire frontline. On October 1, the U.S., along with Russia and France, issued a joint statement as the three co-chairs of the Minsk Group for an end of hostilities and the resumption of talks. However, neither side, not less Azerbaijan, which seems to have the upper hand right now, has shown a desire to return to the negotiating table.

Far from being just a localized conflict in a place far from Washington, DC, the fighting between the Azerbaijani and Armenian militaries and Armenian-backed militias in Azerbaijan’s Nagorno–Karabakh region could destabilize an already fragile region even further. Armenia’s occupation of parts of Azerbaijan is no different from Russia’s illegal occupation of Crimea in Ukraine or its occupation of the Tskhinvali region (South Ossetia) and Abkhazia in Georgia.

If the U.S. is to follow the guidance outlined in its 2017 National Security Strategy, with its emphasis on great-power competition, the current fighting in the South Caucasus cannot be ignored. The U.S. must monitor the situation closely, keep an eye on Russia’s and Iran’s malign influence in the region, seek guarantees that international trade and transit routes passing through Azerbaijan will remain secure, and call for a negotiated settlement that respects the territorial integrity of all countries in the region and is based on the existing Madrid Principles.

A Bloody War

The conflict started in 1988 after the local assembly of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic’s (S.S.R.’s) Karabakh Autonomous Oblast voted to join the Armenian S.S.R. In 1991, a referendum was held in the same region about whether to unify with the Armenia or not. During the referendum, the Azerbaijani minority living in the Karabakh Autonomous Oblast boycotted the vote. Both the local assembly’s vote in 1988 and the referendum in 1991 were considered illegitimate by the government in Baku at the time. This eventually led to a bloody war between Armenia and Armenian-backed separatists and Azerbaijan that left 30,000 people dead, and many hundreds of thousands more internally displaced.

Upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, the newly independent countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan agreed and signed the Alma-Ata Protocols, which stated each country is committed to “recognizing and respecting each other’s territorial integrity and the inviolability of the existing borders.” This included the Azerbaijan S.S.R.’s Karabakh region remaining part of the newly established Republic of Azerbaijan.

By 1992, Armenian forces and Armenian-backed militias occupied the Nagorno–Karabakh region and all or parts of Azerbaijan’s Agdam, Fizuli, Jebrayil, Kelbajar, Lachin, Qubatli, and Zangelan districts. On this occupied territory Armenian separatists declared the so-called Republic of Artsakh. “Artsakh” is a fictitious country and is not recognized by any other country in the world—even Armenia.

During 1992 and 1993, the U.N. Security Council adopted four resolutionsREF on the Nagorno–Karabakh war. Each resolution confirmed the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan to include Nagorno–Karabakh and the seven surrounding districts, as well as calling for the withdrawal of all occupying forces from Azerbaijani territory. A cease-fire agreement was signed by all sides in 1994.

The Minsk Group was established by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) at the Budapest summit in 1994. The OSCE consists of 12 members, with France, Russia, and the United States serving as permanent co-chairs. The Minsk Group was tasked with bringing a lasting peace to the war, but over the years had difficulty finding a framework for negotiations to which all sides could agree.

Finally, in 2007, the co-chairs released the so-called Basic Principles, more commonly referred to as the Madrid Principles, which all sides initially agreed to use as a formula for talks.REF In sum, the Madrid Principles called for a phased approach and a set of confidence-building measures between both sides. This included:

- The withdrawal of Armenian forces from the Azerbaijani territories surrounding Nagorno–Karabakh;

- The resettlement of refugees forcibly removed from their homes during the 1990s; and

- The establishment of transport and communication links between Armenia and Nagorno–Karabakh.

Under the Madrid Principles, the final status of Nagorno–Karabakh would be decided at a future date once the aforementioned steps were taken.REF

Even with an agreed framework for talks, no meaningful progress was made. Also, since coming into power after the so-called Velvet Revolution in 2018, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has called into question the current status and Armenia’s support of the Madrid Principles.REF

An Unfrozen Conflict

Thanks to an economic windfall due to its abundance in oil and natural gas, Azerbaijan has been arming heavily in recent years. For 2020, its defense and security budget is approximately $2.27 billion.14 This represents more than half of Armenia’s entire 2020 state budget of almost $4 billion.15

After years of only minor skirmishes, intense fighting flared up between Azerbaijan and Armenia during a period of four days in April 2016, leaving 200 dead on each side.REF During this time, more than eight square miles of territory were liberated by Azerbaijani forces.REF In early summer 2018, Azerbaijani forces successfully launched an operation to re-take territory around Günnüt, a small village strategically located in the mountainous region of Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.REF Until this current round of fighting, the 2016 and 2018 incidents marked the only changes in territory since 1994.

The current fighting follows a minor skirmish in July along the undisputed state border between the two sides. On July 12, 2020, the Azerbaijani village of AghdamREF in the Tovuz district, nestled along the border with Armenia, was shelled by Armenian forces. This specific incident led to the deaths of four Azerbaijani soldiers. In the subsequent days, a number of skirmishes between Azerbaijani and Armenian forces killed dozens of civilians and soldiers on each side.

The current fighting has already left hundreds of people dead on both sides, including many civilians. Martial law and a full military mobilization have been declared in Armenia. Azerbaijan has also declared martial law and implemented a partial mobilization.

Fighting has been reported along the full length of the front line, but the main focus of Azerbaijan’s operations has been taking place in Fizuli and Jebrayil in the south, and Madagiz in the north. Territory has changed hands, but the exact details at the time of writing remain scarce.

Civilian populated areas have been struck with long-range munitions by both sides. Azerbaijani forces have fired rockets and artillery at targets in Nagorno–Karabakh’s biggest city Stepanakert/Khankendi. Armenian forces have struck several towns and cities in Azerbaijan well outside the area of fighting in Nagorno–Karabakh, including Ganja and Mingachevir. Ganja is Azerbaijan’s second-largest city and a key transport hub. Mingachevir is home to the largest hydroelectric dam in the South Caucasus.REF

Both sides accuse the other of starting the current round of fighting. Determining who “shot first” may never be known and after almost three decades of occupation is not very important. However, there are probably three reasons why Azerbaijan picked now to launch a military operation to restore its territorial integrity.

- It is well known that the main factor preventing Azerbaijan from taking action sooner was the threat of a direct Russian military intervention. Azerbaijan has probably assessed that Russia is so distracted by other matters (such as the global pandemic, as well as Belarus, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine) that it would not intervene militarily on the side of Armenia if major fighting broke out.

- This scale of fighting, not seen in Nagorno–Karabakh since the early 1990s, is probably Azerbaijan’s final cry for help to the international community, which has all but given up trying to resolve the conflict after almost 30 years. If Baku wanted to draw global attention to the situation, it could not have chosen a better way.

- There have been a series of events that have taken place in the past 12 months that have signaled that Armenia is less interested in a negotiated settlement, to wit: Pashinyan’s questioning of the Madrid Principles; the recent announcement of moving the so-called Republic of Artsakh parliament to Shusha—a city of great historical and cultural importance to Azerbaijan;REF the Armenian defense minister’s 2019 speech in New York when he said that his country should be prepared for “new war for new territories”;REF the decision by Armenia to construct a third major road connecting it to Nagorno–Karabakh;REF and Armenia’s resettlement of thousands of Armenian refugees from Syria to Nagorno–Karabakh.REF

Combatting Disinformation. Regarding the current round of fighting there has been a lot of “fake news” and disinformation spreading. Therefore, several facts are important to remember:

- For now, the current fighting is not taking place inside Armenia. All the fighting is taking place on territory that the U.S. and international community consider to be de jure part of Azerbaijan.

- Although Armenia is a Christian country and Azerbaijan is a Muslim majority (albeit secular) country, there is no meaningful religious dimension to this conflict.

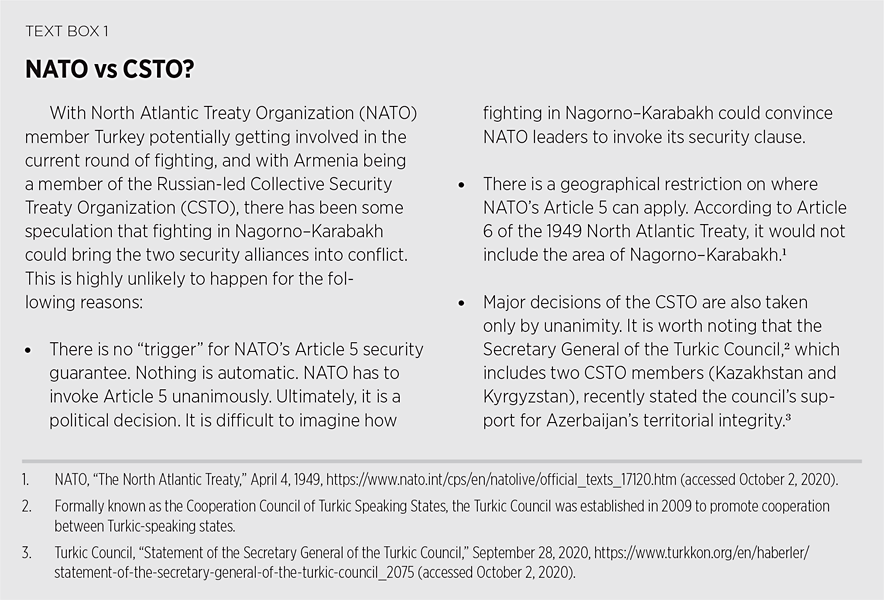

- When it comes to the Nagorno–Karabakh conflict, Russia and Iran have supported, or at least been sympathetic to, Armenia’s position. Turkey and Israel have supported, or at least been sympathetic to, Azerbaijan’s position.

In recent days, evidence has surfaced on social media of Russia transporting hardware through Iran and into southern Armenia. Interestingly, there have also been reports of ethnic Azeri’s living in northern Iran attacking these convoys. Turkey has provided Azerbaijan with effective and battle-tested unmanned arial vehicles (UAVs). More importantly for Baku, Turkey has endorsed Azerbaijan’s military operations in Nagorno–Karabakh.REF

As part of the strategic partnership between Azerbaijan and Israel, the Israelis have also sold very capable UAVs to the Azerbaijanis, which have proven to be incredibly effective in the current fighting.REF In fact, Armenia has since recalled its ambassador to Israel over this point.REF Although Azerbaijan is a Muslim-majority country, it is a secular society and has a very close relationship with Israel. The Azerbaijani city of Qirmizi Qasaba is thought to be the world’s only all-Jewish city in the world outside Israel. Azerbaijan also provides Israel with 40 percent of its oil.REF As a sign of how close the bilateral relationship is between the two countries, Benjamin Netanyahu visited Azerbaijan in 2016.REF

Russia and Iran

For historical, economic, geographical and cultural reasons, Armenia shares a close relationship with both Russia and Iran.

Russia maintains a sizable military presence in Armenia, based on an agreement that gives Moscow access to bases in that country until at least 2044.REF The bulk of Russia’s forces—consisting of 3,300 soldiers, dozens of fighter planes and attack helicopters, 74 T-72 tanks, almost 200 armored personnel carriers, and an S-300 air defense system—are based around the 102nd Military Base.REF Russia and Armenia have also signed a Combined Regional Air Defense System agreement. Even after the election of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, Armenia’s cozy relationship with Moscow remains unchanged.REF Armenian troops have even deployed alongside Russian troops in Syria, to the dismay of U.S. policymakers.REF

Iran is one of the historical Eurasian powers and therefore sees itself as entitled to a special status in the region. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan were once part of the Persian Empire. Today, Armenia and Iran enjoy cozy relations. During the war in Nagorno–Karabakh in the early 1990s, Iran sided with Armenia as a way to marginalize Azerbaijan’s role in the region.

Azerbaijan is one of the predominately Shia areas in the Muslim world that Iran has not been able to place under its influence. While relations between Baku and Tehran remain cordial on the surface, there is an underlying tension between the two over the status of ethnic Azeris living in Iran.REF Consequently, Iran uses its relationship with Armenia as a way to undermine Azerbaijan.

In the past, the Armenian–Iranian relationship has been too close for comfort for the United States. In 2008, for instance, the U.S. State Department accused Armenia of selling weapons to Iran that were later used against, and killed, U.S. troops serving in Iraq.REF Tehran has also invested millions of dollars in infrastructure and energy projects in Armenia.

Ganja Gap under Threat

There are only three ways for energy and trade to flow overland between Europe and Asia: through Iran, Russia, and Azerbaijan. With relations between the West, Moscow, and Tehran in tatters, that leaves only one viable route that is hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of trade—through Azerbaijan.

When you factor in Armenia’s occupation of Nagorno–Karabakh, all that is left is a narrow 60-mile-wide chokepoint for trade out of the more than 3,200 miles spanning the distance between the Arctic Ocean and the Arabian Sea. (See Ganja Gap map.) This trade chokepoint has been coinedREF the “Ganja Gap”—named after Azerbaijan’s second largest city, Ganja, which sits in the middle of this narrow passage. The Ganja Gap is located mere miles from the front lines of the Nagorno–Karabakh conflict and has come under repeated attack from Armenian forces since the recent fighting started.

Currently, there are three major oil and gas pipelines in the region that crucially bypass Russia and Iran and pass through the 60-mile-wide Ganja Gap. (These pipelines include: the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline, which runs from Azerbaijan through Georgia and Turkey and then to the outside world through the Mediterranean; the Baku-Supsa Pipeline carrying oil from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea and then to the outside world; and the South Caucasus Pipeline running from Azerbaijan to Turkey, which will soon link up with the proposed Southern Gas Corridor to deliver gas to Italy and then to the rest of Europe). It is not just Europe that would be impacted if these pipelines were disturbed: Israel gets 40 percent of its oil from Azerbaijan through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline.

Fiber-optic cables linking Western Europe with the Caspian region pass through the Ganja Gap. The second-longest European motorway, the E60, which connects Brest, France (on the Atlantic coast), with Irkeshtam, Kyrgyzstan (on the Chinese border), passes through the city of Ganja, as does the east-west rail link in the South Caucasus, the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway.

The Gap is still used by the U.S. today to provide non-lethal supplies to troops in Afghanistan. In fact, at the peak of the war in Afghanistan, more than one-third of America’s non-lethal military supplies like fuel, food, and clothing passed through the Ganja Gap either overland or in the air en route to U.S. forces in Afghanistan.REF

Recommendations

What happens in the South Caucasus can have regional, transatlantic, and global implications. While the U.S. has no direct military role in the conflict, it is in America’s interest that the conflict does not spiral out of control. The U.S. should therefore:

- Monitor the situation in Nagorno–Karabakh. Peace talks over Nagorno–Karabakh have been stalled for years. The U.S. should continue to call for a peaceful solution to the conflict that includes the withdrawal of Armenian forces from all of Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized territories, based on the existing Madrid Principles, and in line with the relevant U.N. Security Council resolutions from the early 1990s.

- Monitor’s Russia and Iran’s role in the region. The 2017 National Security Strategy places a strong emphasis on great-power competition. The actions of Tehran and Moscow in the region must be watched closely. From maximizing diplomatic influence to selling weapons, Moscow benefits in many ways from the “frozen conflicts” around its borders, including Nagorno–Karabakh. Iran has sought to increase economic and energy ties with Armenia in recent years to lessen the impact of U.S. sanctions. Both aim to undermine U.S. interests in the region.

- Stress the importance of the Ganja Gap remaining open for international transit, trade, and energy. Much of Europe, as well as Israel, rely on oil and gas transiting through the Ganja Gap. The U.S. still uses the Gap to send non-lethal resupplies to its forces in Afghanistan. The U.S. must press Armenia to restrain from attacking this important trade corridor located so close to the front lines of the fighting.

- Maintain military and security relationships with all deserving partners in the region. The U.S. benefits from its security, counterterrorism, and intelligence-sharing relationship with Azerbaijan. The U.S. government’s decision to maintain a defense or security relationship with another country should be based on American geopolitical interests and not certain pressure groups lobbying Congress. When Congress debates the U.S. response to events in the South Caucasus, the number one consideration should be U.S. geopolitical goals in the era of great-power competition, and not emotional appeals by certain lobby or diaspora groups.

Conclusion

Far from being just a localized conflict watched with curiosity by many on social media, the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan is actually a tangled web of competing geopolitical interests from across the region, including Iran, Russia, and Turkey. While the South Caucasus countries are far away, American policymakers should keep in mind that ongoing conflict in the region can have a direct impact on U.S. interests, as well as on the security of America’s partners and allies.

Luke Coffey is Director of the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign Policy, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation.