Americans love to complain about bureaucrats, especially those who have real power—the power to say no when you want to start a new business, market a new product, or merely build on your own property. Where did bureaucrats get so much power to tell us what we can and can’t do? We talked about the power of administrative government, where it came from, and what to do about it with Joseph Postell.

Postell is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs and a visiting fellow at The Heritage Foundation. His book, Bureaucracy in America: The Administrative State’s Challenge to Constitutional Government, was published earlier this year.

The Insider: In your work—especially in your new book—you have written that the administrative state is a threat to constitutional government in America. What do you mean by the term “administrative state” and why is it inconsistent with our constitutional values?

Joseph Postell: In the administrative state, legislative power is shifted from Congress to administrative agencies. Most laws today are made by administrative agencies instead of by Congress. Congress still passes bills, but most of those bills don’t really have any rules in them that you have to follow. They actually give the power to make those rules over to administrative agencies. So now the state that is making the rules you have to live by isn’t an elected, representative, republican form of government. It is now an administrative state where the administrators are telling you what to do and what rules you have to abide by.

Compounding that problem is the problem of having legislative powers, executive powers, and judicial powers all combined in the same agency. Agencies today adjudicate disputes about their own rules—through administrative law judges—as opposed to having to make their case to an independent Article III court.

Instead of Congress—elected representatives—writing laws, and the executive agencies investigating, prosecuting, and enforcing, and then adjudication happening in independent courts like our constitution envisions, we have a system in which unelected bureaucrats and administrators make rules, then they investigate whether people violated those rules, they prosecute, they enforce, and even in many cases they adjudicate.

So now instead of a constitutional system of separated powers and elected representation, we have a system of consolidated powers and unelected bureaucrats making rules. That’s a widespread constitutional problem. In environmental law, in labor law, and in health care law, to take a few examples, that same basic structure threatens the constitutional system.

Most laws today are made by administrative agencies instead of by Congress. Congress still passes bills, but most of those bills don’t really have any rules in them that you have to follow.

TI: How did we end up with this setup that’s so unmoored from the Constitution?

JP: Three things happened. The first is, our country grew massively. The types of problems that we had to deal with seemed to be new problems and they seemed to require some radically new solutions. Industrialization, urbanization—those sorts of problems—seemed to require a brand new form of government.

The second thing that happened was that certain political theorists around the later part of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century—Woodrow Wilson, Frank Goodnow, Herbert Croly, and even political actors like Theodore Roosevelt—made the argument that the old system of government really wasn’t working anymore and we needed a new system of government, that we needed to reject the separation of powers and we needed to reject the idea that our elected representatives make the laws. They wrote these things openly. They didn’t revere the Constitution. They said the Constitution needed to be remodeled in light of new circumstances.

The third thing that happened, after the administrative state had become a reality, was that people started to see that it was a great threat to Constitution-based principles. The progressive approach had been to say openly that the Constitution was outdated and that it was time to find a new path.

More recently, scholars and theorists have been saying that if you interpret the Constitution in a certain way and if you interpret the administrative state in a certain way that it actually could fit with the Constitution that we have. What’s going on, these theorists say, is that these agencies have really just been executing law, not making it. Under this theory, when the Department of Health and Human Services makes a mandate about what essential health benefits insurance plans have to provide, they’re really just executing the Affordable Care Act.

So the third thing that happened was that there was this creative, semantic game that a lot of political and legal theorists played to try to retrofit the administrative state into the Constitution. But that semantic move doesn’t really fit the Constitution as it was understood by the people who wrote it and the people who ratified it.

TI: You used the word “seem” a few times there to describe the supposed necessity of administrative government. It seems you are skeptical of the idea that a bigger society can’t stick to the constitutional design of 1776. Right?

JP: One of the arguments that people make today—probably the most powerful argument in favor of the administrative state—is simply the argument from necessity.

According to this view, you can’t have members of Congress who aren’t really experts making decisions about air quality, pollution levels, workplace safety standards, the regulation of drugs, and so forth.

In other words, the necessity argument says times have changed, society is more complicated now and we need experts to be in charge. I am skeptical of that argument because I think it overstates the change in circumstances between the time the Constitution was written and ratified and where we are today.

Society was really complicated even at the time the Constitution was written. The Founding generation had to solve all kinds of difficult problems. One of the things I do in my book is to show that the kinds of problems that they had to solve were extremely complicated even in the 18th century and the early part of the 19th century.

JOSEPH POSTELL, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and Visiting Fellow in American Political Thought at The Heritage Foundation.

And the people who were working in politics at that time managed to come up with regulations to solve the problems of a complex society without resorting to this brand new fourth branch of government with consolidated powers and unelected rule makers.

They still managed to fit regulation into the constitutional system. And they did it by believing in the principles that the Constitution set up and following those principles. They believed that if we are going to have regulations, then the people who write regulations have to be accountable and they have to be elected. And then if we are going to have enforcement of those regulations, the people enforcing and adjudicating have to be separate from the people who write the regulations.

So I am skeptical that the times have changed so much that we need to depart from the constitutional design we came up with.

TI: What does a regulatory state that is consistent with the Constitution look like? What agencies do we have now that would not exist or not exist as we know them if we adhered to the original design of the Constitution?

JP: There are a bunch of agencies that are not a constitutional threat. The Post Office is not a constitutional threat. Whether it’s managed well is a separate question.

The Post Office isn’t writing rules of conduct that we all have to follow lest we get fined or imprisoned. The Patent Office has been around for a long time and that’s not really a constitutional threat.

It’s modern agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Labor Relations Board—all created since 1900—that are the problem and need to be radically altered.

I don’t think any of those agencies needs to be eliminated completely. Probably what needs to happen is that they would need to become executive agencies again, meaning that Congress has to write a law that those agencies then enforce.

If Congress wanted to write a law that mandates there be no lead beyond a certain point in the ambient air and they say in the legislation how much lead we can have in the air, you’d still have to have the Environmental Protection Agency to investigate whether industries are violating that law.

But the Environmental Protection Agency wouldn’t be setting the standard, and the Environmental Protection Agency would have to go through an independent federal court to get an enforcement of any of its prosecutions. That I think would look very similar to the early approach that fit within the constitutional system.

TI: How detailed does Congress need to make its laws in order to avoid unconstitutionally delegating its legislative powers?

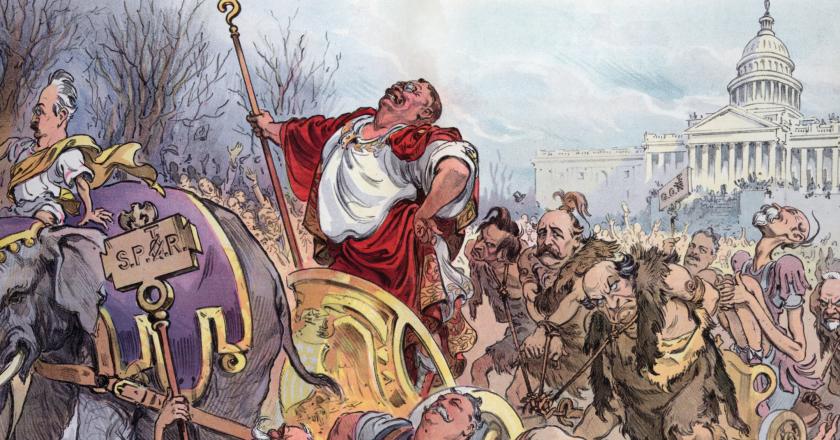

WHO WILL STAND UP TO THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE? Among the leading critics in the Senate are Marco Rubio (R, Fla.) and Ted Cruz (R, Texas) (sitting on the left and right, respectively, of Secretary of Labor nominee Alex Acosta), Rand Paul (R, Ky.) (bottom left), and Ben Sasse (R, Neb.) (bottom right). (credit: KEVIN DIETSCH/ MICHAEL BROCHSTEIN/ JEFF MALET/NEWSCOM)

JP: That is a very hard question to answer. In fact, many of the leading theorists can’t give a bright-line response to that question. I would say, first, Congress would have to write the statutes in much greater detail than it does now in order to meet any standard for delegation. Wherever we would draw that line, Congress is not even close to it today.

That said, it’s very difficult to find out where the line is between enforcing a law versus making law. An example I like to use involves the signs with which we are all familiar in restaurant bathrooms that say: “Employees must wash hands before returning to work.”

These signs are typically required to be posted in restaurant bathrooms by a law that says they must be “clearly visible.” Is that sufficiently detailed? Can an agency make rules defining the dimensions of the signs, the font sizes, and so forth. Maybe an agency needs to make a rule about those matters. Does that mean that the agency is writing the law? No, we wouldn’t say so in that case.

It’s a really hard thing to define the difference between legislation and execution of the law. That said, today we have gone way over that line. We’ve been giving essentially wholesale legislative powers to executive agencies.

I think the right approach would be to start bit by bit and go piecemeal. Every five years, the Clean Air Act Requires the EPA to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards. Why couldn’t we say that air quality standards have to be written by Congress? Those are clearly laws. Nobody knows what they have to do to comply with the Clean Air Act until the EPA writes the air quality standards. Right now the statute says that the EPA Administrator shall make air quality standards that protect public health. Nobody knows what that actually means until the agency makes the standards.

So maybe a good rule would be something like this: If you can read a statute and know what it is you have to do to comply with the law (not in every particular but in general), then it’s not a delegation. But if you can read a statute and have no idea what your legal responsibilities are until after the agencies start making the rules, then you’ve got some sort of delegation problem.

TI: If laws had to become more detailed, wouldn’t it be harder for Congress to find the majorities it needs to pass laws? Is there a danger that Congress would end up in gridlock if it couldn’t delegate some of its rulemaking authority?

JP: That is a genuine concern, but the idea that members of Congress can’t agree that we should not have lead in the ambient air doesn’t give enough credit to our Congress and it doesn’t give enough credit to the people who elect those members.

The argument that Congress can’t do the job is a subtle and veiled criticism of self-government and representative democracy in general. What they’re saying is that we can’t trust the people and their elected representatives to make these decisions.

If that’s what the defenders of the administrative state actually believe, then they should just come out and say so. But I think a lot of people still believe in this idea of self-government and of representative democracy.

If you try things piecemeal by following these principles in a few areas of law and see how that goes, then maybe that will begin to rebuild the kind of habits of self-government that we need to practice a little bit more than we’ve been doing over the past century.

Our Founders always talked about this country as an experiment in self-government and it’s up to every generation to make sure that experiment is a success. And so it is really incumbent on us to at least try to work through these problems through the constitutional mechanisms we have instead of taking the easy way out and saying let’s let the experts handle that.

TI: Under the current setup, congressmen vote for good-sounding stuff and then blame the bureaucrats when people don’t like the resulting rules. congressmen like that arrangement, don’t they?

JP: That’s absolutely right. Members of Congress are very much aware of how dangerous it is for them to have to be accountable for the rules that our government makes people follow. You can attribute most of the delegation problem to members of Congress getting together and saying: Hey, we can’t come together on a solution to this problem; therefore let’s just have a bill that looks like a solution but really leaves it to some agency to construct the right solution. That way we can look like we solved the problem even though it’s going to be some agency that really solves the problem while also incurring all the political blame that goes with that solution.

You can explain most of delegation through that simple structural incentive for members of Congress to duck responsibility but take credit.

TI: Then how do we get Congress to change its delegating ways?

JP: In large part it’s up to us. We have to be able to follow the trail a little better than we have done over the past century. We love to chastise bureaucracy in this country. But we do need to understand that bureaucracies are largely beholden to our elected representatives.

The real problem here is a problem with our political branches, not just with our administrative state. In part we need better education about how our government works so that people can hold the right officials accountable for bad laws.

If the Food and Drug Administration behaves badly we should be aware that it’s not just the FDA that’s responsible. It’s the members of Congress who are supposed to be overseeing that agency and more importantly supposed to be doing the work that they transferred to that agency.

TI: Are the courts an innocent bystander in the rise of the administrative state or have they played a role, too?

The argument that Congress can’t do the job is a veiled criticism of selfgovernment and representative democracy in general.

JP: The courts have played a massive role. This problem is one people don’t pay enough attention to. The courts have played two major roles in the birth and then the expansion of the administrative state.

The first was a role of hands-off. The Constitution clearly says: “All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress […] .”

And if the Supreme Court wanted to enforce that rule, it could. It could say whether a statute unconstitutionally transfers legislative power instead of keeping it within Congress.

The courts had a role to play in policing how much power was going to be transferred to the bureaucracy. But the courts, largely because they were intimidated by the political branches—in particular by the presidents during the early part of the 20th century—decided that they could no longer police those boundaries. They decided it wasn’t possible to stand up to people like Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt and win. So the Court stopped policing the constitutional boundaries that had prevented the administrative state from emerging.

The second thing the courts did with regard to the administrative state was to begin to police the agencies—not to police the boundaries between the powers but to police the agencies themselves. Courts today routinely supervise agency rulemaking and agency adjudications to make sure agencies are following the right procedures, that they are interpreting the laws correctly, and that they are making substantive decisions that are reasonable.

One prominent example occurred after the Bush administration’s EPA determined that it didn’t have the power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from automobile tailpipes. Twelve states and the District of Columbia, along with numerous other entities sued the Environmental Protection Agency to get that rule overturned. The Supreme Court said, in Massachusetts v. EPA, that the Environmental Protection Agency has the power and the responsibility to regulate greenhouse gas emissions related to climate change.

That’s an example of the Court telling the agencies what to do. And the courts do this all the time. So today the courts are not hands off; they are actively pushing some of these regulations through, even when bureaucracies don’t want to make them.

TI: Is the Supreme Court’s Chevron Doctrine of deference to agency interpretations of law part of the problem?

JP: Yes. The Chevron Doctrine says as long as agency interpretations of the law are reasonable, they are going to be upheld by courts. When the law is written to give the agencies so much leeway, that means they get deference from the courts on how they interpret something like the Clean Air Act or the Affordable Care Act.

The whole point of courts is to interpret the law. A judiciary that says “we’re going to let the executive interpret the law and defer to the executive” gets the constitutional system completely wrong.

Chevron is wrong on constitutional grounds. The whole point of courts is to interpret the law. A judiciary that says “we’re going to let the executive interpret the law and defer to the executive” gets the constitutional system completely wrong.

It’s wrong as a matter of history. There is no historical foundation for the Chevron Doctrine.

And it’s wrong as a matter of policy. The whole point of the constitutional system is to prevent the consolidation of power in the same hands. But courts basically say to agencies: OK you write the rules; you interpret the statutes that you have at your disposal through the writing of those rules, and we’ll give you deference. That has consolidated government power in the hands of unelected bureaucrats.

So I think Chevron is wrong on constitutional grounds, on historical grounds, and on policy grounds. People are increasingly starting to see the problem with Chevron. I do not think Chevron, at least as we know it today, will be around for much longer.

TI: Instead of deferring to agency interpretations, what should judges do when they are confronted with a law that is truly ambiguous

JP: The whole point of a judiciary is to interpret the law. When the law doesn’t have any meaning, how do you interpret the law? When the law says, go make the air clean, how do you interpret that as a judge? The problem here is that most statutes aren’t laws.

But judges should exercise their own independent judgment about the meaning of the law based on what the people who passed that law were thinking when they passed it. There are a lot of laws where we know legislators meant X and not Y. Judges should be able to say that if the agency violates that presumption then they are not going to get deference. Judges should interpret the statute independently.

It’s not going to be easy for judges to assume this role of interpreting statutes again, especially given how vague the statutes are. But at the same time, that’s the responsibility of the courts. And maybe if judges exercise independent judgment more, they will force Congress to write statutes a little bit more clearly.

TI: If a law truly has no meaning, would it be appropriate for a judge to say: This is not a law that grants the executive branch any power to enforce anything?

JP: That is a situation where you see the interaction between the Chevron principle and the non-delegation doctrine. If we got rid of Chevron then the judges would interpret a law independently. But if the law doesn’t have any meaning, the judges could then say it was a delegation of power and return the law to Congress for a statement on that question.

TI: Other than being in a different place in the government’s flow chart, what’s the difference between an administrative court and an Article III court?

JP: The paychecks of administrative law judges are paid by the agencies themselves, so they work for the agency whose rules and whose decisions they are supposed to be reviewing. Administrative law judges are protected from retribution by their superiors in certain ways. You can’t reduce the salary of an administrative law judge if you don’t like that he ruled against you.

But it’s still the case that those judges are not independent of the agencies whose rules they are supposed to be applying, whereas an Article III judge actually has independence. The judge’s salary is independent of the agency and, just as important, the judge’s tenure in office is not subject to the agency’s control.

Surveys of administrative law judges routinely show that they don’t think they are independent of the agencies. And therefore when they are making decisions about the agency’s rules, they are going to be siding with the agency.

Article III courts on the other hand are independent of the agencies; they will be willing to check an agency because they will have that freedom from supervision by the agency.

A critical feature of constitutional government is that you are not subjected to a judge who happens to be in cahoots with the prosecutor. The only way to get that is through independent Article III judges as opposed to these administrative law judges we have today.

TI: Is there anybody in politics right now who is a potential champion of rolling back the administrative state?

JP: I think we have a lot of senators right now who are potential champions of restoring constitutional government by taking on the administrative state. Four that come to mind are Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, Rand Paul, and Ben Sasse.

Marco Rubio in particular has thought about these issues very carefully. He has proposed things like regulatory budgets for different agencies. All of these senators have, in their own ways, talked about the problems of the administrative state. I think we are in a better position now than we’ve ever been to understand the problem and to think about how to deal with it.

TI: Other than having Congress incrementally reclaim from the bureaucracy the authority to write the rules, what is your plan for bringing government back to its constitutional moorings?

JP: There are piecemeal, small-scale reforms; and then there are bigger reforms. In the category of bigger reforms I would suggest a couple of other ideas—more on the judicial side than the legislative side.

There is the REINS Act, which says that Congress has to actually write the rules. There is another bill that has suggested making cost-benefit analysis part of the judicial review process.

(credit: ISTOCKPHOTO)

The best idea is to take the power of adjudication away from administrative law courts and give it back to independent Article III courts when a decision of an administrative agency affects actual rights of citizens.

Adjudications, for example, involving workplace safety standards or decisions by the National Labor Relations Board are the kinds of things that really need to be decided by independent judges. I think it might be even more important than getting Congress to write its own rules.

TI: Isn’t this argument just a fussy hang-up over process? Voters care about things like the economy, health care, and the environment. Why should they care about the process by which the government reaches its decisions?

JP: Two reasons. The first is that process is politics. If you allow the government to use a process in which it’s not accountable to the people, and if you allow the government to use a process in which the same person is lawmaker, prosecutor, judge, jury, and executioner, then you are going to get bad policy outcomes.

The economy is going to be worse if the regulations are not made by people who are accountable and if they are not enforced by independent judges.

There is an obvious relationship between the growth of the administrative state and the growth of regulation that potentially stifles the economy. So if you have bad process, you have bad policy.

The second reason is that if you ever find yourself at the mercy of one of these administrative agencies, you will very quickly learn how dangerous it is to have government officials with the power to make arbitrary decisions.

People often talk to me about their run-in with some bureaucrat who didn’t really have any checks on his power, and who got to make the law, who got to enforce the law, who got to prosecute the law, and then who got to adjudicate the law.

They realize very quickly that that is the definition of a lawless system. There is no law in that system. It’s complete arbitrary will—namely the will of the administrator who can use the power of government to control your behavior.

So it’s not just a question of process affecting policy. It’s a question of process affecting your daily life and of whether you will be confronted with that situation at some point. Maybe you will need a building permit to renovate your home. Maybe you will want to open a business. Maybe it turns out you have an endangered species on your property.

Anything like that, you will very quickly realize you’ve run into arbitrary government and you have no rights whatsoever.