In the decades since its creation by the British in 1947, Pakistan has been ruled more often than not by authoritarian martial-law regimes, interspersed with episodic attempts to establish genuine democracy. The two most famous democratically elected prime ministers in the country’s short history are the late Benazir Bhutto of the center-left Pakistan Peoples Party, who served twice and was assassinated in 2007, and the current occupant of that office, Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, who returned to power for a third (non-consecutive) term in 2013 when his center-right Pakistan Muslim League was elected with a sweeping majority vote amidst an unprecedented 60 percent voter turnout. Nawaz Sharif’s election raised hopes that Pakistan might have finally entered a period of more stable democratically elected governance with a government that vowed to follow a forward looking foreign policy and pursue reforms that valued economic freedom.

The Nawaz administration promised major economic relief from what it called a “lethal combination of low growth and high inflation.” Pakistan’s economy, however, continues to stagnate, showing no sustainable improvements. The International Labour Organization (ILO) predicts that unemployment rates will remain above 5 percent until 2018—lagging significantly behind global and regional averages in the rest of South Asia.[1] The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects Pakistan’s future economic growth to be relatively sluggish at best, reaching 4.7 percent by fiscal year (FY) 2016, owing largely to lower world oil prices. Pakistan is growing significantly more slowly than its neighboring South Asian economies, however, which are expected to grow an average of 5.4 percent during that period—with Bangladesh at 6.3 percent, Sri Lanka at 6.5 percent, and India at 8.1 percent.[2]

Meanwhile, Pakistan is also suffering from an electricity crisis that is considered to be one of the root causes of its economic woes. Chronic power shortages across the country adversely impact the manufacturing and industrial sectors. The country can produce only about 12,000 megawatts (MW) of electricity while facing demand that has reached 19,000 MW; energy supply will be 64 percent short of energy demand by 2030, according to the Planning Commission of Pakistan.[3] As the world enjoyed the benefits of low fuel prices early in 2015, Pakistan was experiencing fuel shortages that led to country-wide protests culminating in the shutdown of businesses in the Pakistani capital and major cities in Punjab province. These shortages were partly caused by the internal debts of about $1.7 billion owed by the Power and Water Ministry to the state-owned Pakistan State Oil company.[4]

Regional conflicts, aggravated by the Pakistani military’s dogged interference in the Pakistan civilian government’s foreign policy, have also severely constrained economic growth in Pakistan. Increasing levels of terrorist activities both within the country and on Pakistan’s borders with Afghanistan, as well as the ongoing negative fallout from long-standing territorial conflicts with India, continue to be barriers to foreign investment and a flourishing business environment. Even though Pakistan’s trade freedom overall has increased, trade shares with neighboring countries—especially India—have dwindled due to numerous physical, bureaucratic, and security-related barriers.

These security and political maladies, however, certainly do not bear sole responsibility for the persistent decline of the Pakistani economy. For years, Pakistani civilian governments have blamed the country’s economic deterioration on the security situation, when in fact it is the lack of sustained reforms that has largely hindered growth. It is not the security problems of Pakistan so much as the massive public-sector corruption, the over-regulation of energy and power services, and the lack of decisive reforms in the tax system that have resulted in a significant decay in the livelihoods of the people, and may even have contributed to increased militant activities in the region and the ensuing radicalization of many young Pakistanis.

This Special Report will examine the major concerns for Pakistan’s economic freedom in the immediate and long-term future—concerns that threaten the country’s prosperity and the welfare of its people. This Special Report will conclude by outlining reforms and policy changes that the Pakistani government must undertake to truly revive Pakistan’s economy.

I. Economic Freedom: Undermined by Corruption, Bureaucracy, and Foreign Aid Dependence

Dependence on Foreign Aid Has Led to Warped Priorities. Since the late 1980s Pakistan has increasingly relied on foreign assistance, in the form of grants or loans, to keep its economy afloat and bridge the gaps caused by persistent deficits. Pakistani governments have been overspending for decades, in part due to increases in debt servicing, large subsidies to public-sector enterprises (PSEs—specifically in the electricity sector), and questionable development spending. The result has been an almost permanent budgetary gap—8.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the 1960s, and 8.5 percent in 2012[5]—that has meant unending reliance on external borrowing. Recent trends have shown an improvement to 5.5 percent in 2014, due to the government’s efforts to reduce expenditures and a growth in tax revenues; according to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), however, this improved performance was supported by several one-off inflows—including the fact that the government did not provide the de facto subsidies to the electricity generation/distribution sector in FY 2014[6] by paying off that sector’s “circular debt” as it had in prior years.[7]

The U.S. has provided economic and military aid to Pakistan since its creation in 1947, with total aid from 1951 to 2011 of $67 billion.[8] Pakistan is the fourth-largest recipient of U.S. aid, after Israel, Afghanistan, and Egypt. The 2009 Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act[9] represented an effort to facilitate sustainable economic development and allocate a higher share of U.S. aid to economic growth-related assistance, and included a promise to increase assistance to as much as $7.5 billion between 2010 and 2014. As a result, since 2009, 41 percent of all American aid to Pakistan has been non-military.

Although the Obama Administration reduced overall assistance for Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iraq in FY 2014, funding to Pakistan of $1.16 billion is still significant compared with the total U.S. spending allocation for Global Hunger and Food Security ($1.06 billion), the Millennium Challenge Corporation ($0.9 billion), and the Global Climate Change Initiative ($0.48 billion).[10]

In addition to economic and military aid from the U.S., Pakistan also receives significant development assistance from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Japan, the United Arab Emirates, the U.K., and other EU countries. In 2014 alone, Saudi Arabia, a strong ally of Pakistan, made a low-profile loan of $1.5 billion to boost Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves and help the country kick-start some infrastructure-related projects.[11]

The continuing balance-of-payments crisis and insufficient foreign exchange reserves have prompted the IMF to sign 12 agreements with Pakistan since 1988. With each agreement, Pakistan pledged to endeavor to reduce its balance-of-payments deficits and raise the level of reserves,[12] and each time it failed to do so. The most recent IMF bailout was a loan signed in 2013 for $6.6 billion under a 36-month Extended Fund Facility, notwithstanding the fact that Pakistan had not met some of the conditionality terms of its previous IMF package signed in 2008.[13] Tax revenue targets were not met, and Pakistan requested relaxation of budget deficit targets to avoid excessive cuts in development spending.[14]

Under the extended IMF agreement of 2013, the Pakistani government pledged yet again to raise revenues via tax reforms (especially by substantially enlarging the tax base), reduce inefficient and costly electricity subsidies, and increase tax compliance.[15] One of the prominent policy steps the government was expected to take was to provide autonomy to the central bank—the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP)—so it could manage the reserves with fiduciary independence.[16] The plan was to empower an independent committee to design and implement a robust monetary policy and disallow any new direct lending from the SBP to the government.[17] To that end, the State Bank of Pakistan (Amendment) Act of 2014 was introduced by the government in early April 2014.[18] The bill was expected to strengthen substantially the monetary policy committee, improve the operational independence of the SBP, enhance its governance structure, and strengthen the personal autonomy of board members.

Unfortunately, in the months since, the Pakistani government has demonstrated by its actions that it is hesitant to relinquish control of the SBP and, most importantly, the currency. Pakistani journalist and economic analyst Khurram Husain succinctly summarizes the skewed relationship between the IMF and Pakistan:

[The] history of continuous injections from abroad inculcated a warped sense of priorities in successive governments. Rather than focusing on reforms to “mobilize domestic resources,” that is, to encourage tax reforms and encourage productivity to promote exports in a rapidly globalizing world, the emphasis for successive governments came to be on ensuring the release of the next tranche of dollars from the Fund.[19]

Indeed, this cycle of misplaced priorities continues to harm Pakistan’s overall economic progress; persistent injections of fresh IMF lending only stabilize the economy temporarily, and (absent reforms) set Pakistan up for another default. External debt servicing in Pakistan continues to shrink reserves—in fact, 40 percent of Pakistan’s federal spending in 2014 went toward repaying external debt reaching nearly $7 billion.[20]

Nevertheless, the vicious cycle of debt continues. With the most recent IMF loans, the country will again be burdened by an even larger debt service payment in the next few years. Yet in March 2015, the IMF’s executive board cited some improvements as it approved the release of a tranche of $501.4 million. For the last quarter of 2014, at least, the Pakistani government had met all the conditions set by the IMF, meeting performance criteria that included a Net International Reserves target, Net Domestic Assets target, reducing general borrowing, reducing borrowings for budgetary support from the SBP, and fulfilling the condition on debt-swap arrangements.[21] Some news reports contend that the reduced borrowings target was only met because the government borrowed from commercial banks instead of the SBP, which in turn facilitated the provision of loans to the government by those commercial banks through the injection of more money into the banking system—a strange sort of “reverse sterilization” process.[22] Thus it appears that the government of Pakistan essentially found—yet again—a round-about way of borrowing from the central bank while meeting its IMF Extended Fund Facility target.

Meanwhile, the IMF continues to urge the government to make progress in tax revenue collections and reduce electricity subsidies, which, as discussed in detail below, are yet to be reduced. Indeed, most of the IMF’s recommended economic reforms have not been unequivocally implemented.

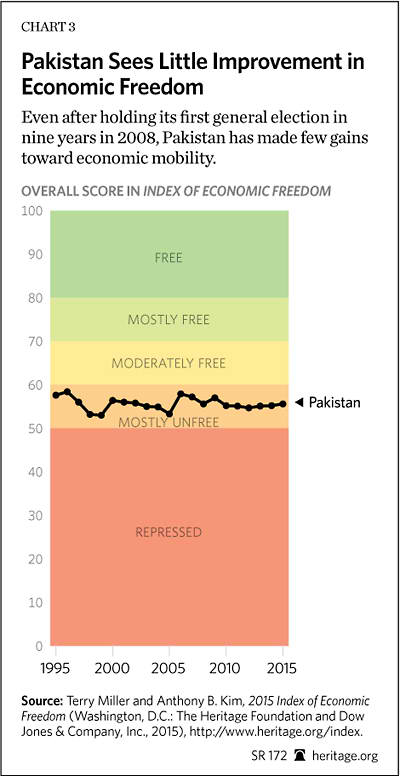

Hopes for Economic Freedom Collide with Sobering Growth Trends. The 2015 edition of the Index of Economic Freedom, published annually by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal, ranks Pakistan “mostly unfree,” with a score of 55.6 out of 100, well below the world average (60.4) and regional average (58.8). Pakistan is the 121st freest of the 178 countries across the world measured in the Index and stands at 25th of the 42 countries in the Asia–Pacific region.[23] While Pakistan’s economic freedom has shown modest improvements over the years, that progress has been counterbalanced by poor scores in rule of law, investment and business freedom, and labor freedom. Overall, the country has remained only slightly above the lowest “repressed economy” Index category.

The Index findings are confirmed by other reports. For example, according to United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) figures, Pakistan ranks 146th (of 187 countries) on the Human Development Index (HDI). Pakistan stands in the lowest human-development category with a score of 0.537, lower than the South Asian average of 0.588. Pakistan is one of only a handful of Asian countries in this category.[24] Most countries in the low HDI category are in Africa and the Middle East.

Some improvement is seen after 2008, the year in which Pakistan held general elections after nine years of dictatorship under General Pervez Musharraf. The country, plagued by military coups for decades, completed a five-year term under President Asif Ali Zardari’s Pakistan Peoples Party. To his credit, Zardari helped the country transition to an official democracy.[25] However, meager economic growth was recorded in those years. The Zardari administration blamed the slow growth rates on the massive floods that ravaged the country in 2010.[26]

One of Zardari’s achievements was the devolution of powers through the 18th amendment to Pakistan’s constitution, passed in 2010. The amendment transferred some governmental powers to the provinces and restored parliamentary sovereignty, but corruption, cronyism, lack of reforms, and absence of a strong provincial leadership have all undermined the importance of this initiative.

In fact, it was double-digit inflation rates, lack of jobs, an unrelenting energy crisis, and a choked economy during Zardari’s tenure that ensured that the Peoples Party was not re-elected for a second term.

Nawaz’s performance after almost two years in power remains mixed at best. The IMF estimates slow economic growth of less than 5 percent in the next few years, while GDP per capita projections also remain tepid. More important, no improvement has been seen in the living conditions of the public. Though GDP growth rates are higher than they were in 2009, investment is only 10 percent of GDP, and poor revenue mobilization ensures continued fiscal deficits.

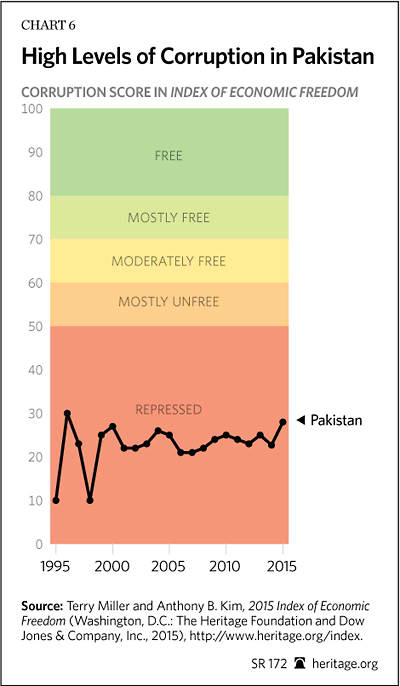

Weak Rule of Law Feeds Widespread Corruption. The Index of Economic Freedom reports that Pakistan is a repressed economy with regard to the rule of law, suffering from widespread corruption, lack of transparency, and little protection, if any, for property rights. Political interference in the judicial system is also prevalent.

A report published in 2010 by the International Crisis Group on reforms needed in Pakistan’s criminal justice system discusses at length the inefficiencies of the justice system, the failure to prosecute crimes, low conviction rates (at most 10 percent of prosecutions), and the larger issues of political and military interference in the judiciary that heavily compromise cases before they even go to courts.[27] The report notes:

A military-led counter-terrorism effort, defined by haphazard and heavy-handed force against some militant networks, short-sighted peace deals with others, and continued support to India and Afghanistan-oriented jihadi groups, has yielded few successes. Instead, the extremist rot has spread to most of the country. The military’s tactics of long-term detentions, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings provoke public resentment and greater instability, undermining the fight against violent extremism.[28]

The report goes on to mention cases such as the 2008 bombings of the Danish embassy and Marriott Hotel in Islamabad, for which prosecutors have never obtained convictions.[29] Many of these cases could have been sabotaged by military intervention. A recent example of this is the release order of Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi by the Islamabad High Court. Lakhvi, leader of the terror group Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT), was suspected of masterminding the 2008 bombings of hotels in Mumbai, India, that claimed 160 lives, including six Americans.[30] Lakhvi was first granted bail by Pakistan’s Anti-Terrorism Court only a few days after the Peshawar attack in December 2014. That attack, carried out by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), claimed 141 Pakistani lives—including 132 school-age children.[31]

It was hoped that this debilitating terrorist attack would bring some perspective to the Pakistani army’s approach in handling all terrorism in the region. On the contrary, Lakhvi’s release only proved to be an indication that the judiciary was likely strong-armed by military leadership to let him go, in a bid to let India know that LeT would remain a blunt foreign policy instrument for Pakistan.[32]

Another major cause of the poorly functioning judiciary in Pakistan is the absence of a uniform legal system. Freedom House’s 2014 Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties reports that one of the principal causes of judicial inefficiency is the confusion caused by overlapping legal systems across the country that lead to “unequal treatment.”[33] Rather than relying solely on the nation’s secular civil and criminal statutes, parallel legal systems based on sharia law and tribal law are often used to determine outcomes in many cases. Several communities in tribal areas subscribe to informal, traditional, and often arbitrary forms of justice. For example, Pakistan’s Supreme Court and parliament do not have jurisdiction over the semi-autonomous federally administered tribal areas (FATA) of Pakistan (roughly the size of South Carolina). This has meant that the justice system in the FATA is controlled by specially appointed community leaders under a statute called the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR).[34] The FCR is a law that was drawn up by the British colonial rulers in 1901 and allows tribal leaders in the FATA to decide the fate of any and all accused of criminal activity in the region. The Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa provincial assembly passed a resolution to repeal the FCR in 2011, but nothing more than cosmetic changes have been made in the years since. The FATA region is still under the control of these local politicians and tribal chiefs rather than conventional law enforcement agents.

Endemic corruption also plagues Pakistan at all levels of government bureaucracy. According to Transparency International’s 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), scaled from 0 to 100, Pakistan is highly corrupt, with a score of 29, and ranks 126th most corrupt of 175 countries measured.[35] Although the scores have improved marginally since 2012, the CPI continues to place Pakistan in the “Highly Corrupt” category. The CPI’s chapter on Pakistan reports that Pakistan lost $94 billion due to corruption, tax evasion, and bad governance during the four years of Zardari’s Peoples Party government.[36] By comparison (and notwithstanding both nations’ legacy of Anglo-Saxon legal systems), next-door neighbor India ranks 85th on the CPI with a score of 38, up from 36 in 2012—corrupt but improving.[37]

According to the World Bank, corruption in Pakistan is also a significant and growing deterrent to foreign trade and investment.[38] More than half of all Pakistani firms (57 percent) consider corruption to be a severe constraint in doing business. This figure has increased from 40 percent in 2002 and is much higher than in the most competitive countries, with the exception of Brazil and Bangladesh.[39] More recently, Walt Disney cancelled nearly $200 million in textile orders from Pakistan and banned the country as a supplier, citing massive corruption, lack of accountability, and violence among the reasons for the ban.[40] A Canadian textile company also discontinued business with Pakistan, claiming that it had become increasingly difficult to do business with Pakistan due to poor infrastructure, unplanned delays, power shortages, corruption, and overall instability in the country. Given that more than half of Pakistan’s total exports consist of textile and textile products, these cancellations are devastating to the country’s economy. Anecdotal evidence gathered by the authors of this Special Report suggests that, in general, instability within the country and corrupt governance continue to affect the business environment and prospects for foreign investments.

The Pakistani tax system is riddled with tax exemptions. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2014, tax exemptions enjoyed by many business elites and companies amounted to nearly $4.7 billion in FY 2014, almost 100 percent higher than the preceding year. The government has promised to phase out these exemptions in three years.[41]

Tax evasion is also rampant in Pakistan, but no administration has managed to deal with it head-on. Only one in every 200 citizens in Pakistan files income tax returns. In 2014, the government published a list of tax defaulters in an effort to shame evaders to pay,[42] but such soft measures are not likely to bear substantial fruit.

According to a report published by the Center for Investigative Reporting in Pakistan, only about a third of Pakistani lawmakers filed income tax returns in 2012; among the 67 percent of non-filers was then-Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gillani.[43] Many lawmakers, the report says, are not even registered taxpayers. Many of those who did file were found to have mis-declared their annual earnings.[44] In fact, the report cites astonishing figures: Less than 1 percent of Pakistanis filed tax returns in 2012,[45] while the country’s tax-to-GDP share was only 10 percent[46] (essentially due to a low tax base combined with high rates). The report explains why the IMF emphasized to Pakistan’s government the need to focus on tax evasion and tax compliance—one of the primary conditions of the 2013 IMF Extended Fund Facility of $6.6 billion.

Regulatory Inefficiency—the Main Culprit in Pakistan’s Power Crisis. About 80 percent of Pakistan’s electricity is generated from imported oil and gas.[47] In fact, oil represents 35 percent of total imports in Pakistan. The import bill for these hydrocarbons will reach an estimated $124 billion by 2020,[48] an amount that Pakistan will in all likelihood not be able to afford. Pakistan has almost exhausted its known gas reserves and will continue to be dependent on imported fuels. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey, “the pronounced shift from hydro to thermal generation, and more recently from natural gas to fuel oil as the primary fuel for electricity generation” has caused a major fuel crisis contributing to significant increases in power supply costs.[49] Electricity supply in Pakistan is presently about 5,000 MW short of daily demand, and that persistent shortage is increasing by about 5 percent per year. Generated from expensive imported fuels, high prices for electricity have, in turn, driven some consumers to participate in widespread theft of it. Exacerbating the power sector’s problems is the fact that one-quarter of all energy produced is lost due to inefficient power distribution networks, poor infrastructure, and mismanagement.[50]

According to the Pakistan State Bank Annual Report for 2014, the power crisis has fundamentally stifled any hopes for industry growth. Even though some industries have reduced their dependence on imported fuel oils by using alternative energy sources—such as biomass and locally mined coal, solar thermal, and combined-cycle gas—leading to short-term positive impact on production, smaller industries remain at a loss.[51] The report notes:

Energy constraints have changed the dynamics of Large Scale Manufacturing (LSM) in the past several years. Hard pressed by energy shortages, a large number of industries are in the process of converting to alternate energy setups. However, given the high cost involved in this shift, not all firms have the resources to do so. Hence, smaller firms involved in the production of glass, paper, and textile (especially units in the informal sector) are either closing down, or are forced to curtail their operations.[52]

Public discontent over massive fuel shortages has brought Pakistanis to the streets and sparked violence in major cities. In January 2015, 95 percent of gasoline stations in the relatively affluent city of Lahore ran out of fuel to sell.[53] At the macroeconomic level, when industries are no longer producing, they no longer need as much human capital, leading to massive layoffs, which analysts believe are the ultimate long-term repercussions of the power crisis: chronic unemployment and increasing radicalization—especially among the youth.[54]

The Vicious Cycle of Electricity-Related “Circular Debt.” The dilemma of “circular debt” is a phenomenon that emerges from the difference between higher production costs of electricity and the lower total revenues accrued from the rate payments received from consumers, with the government subsidizing the shortfall.

The supply chain for power generation in Pakistan operates in a non-transparent manner: The government’s Central Power Purchase Agency (CPPA) purchases each unit produced by generation companies (GENCOs) and then sells them to state-owned power-distribution companies (DISCOs). GENCOs include independent power producers and the state-owned Water and Power Development Authority. The GENCOs purchase oil from local and international oil marketing companies to generate the electricity.

All of the DISCOs are government-owned and government-run; they are largely misgoverned and themselves are sources of massive corruption. The DISCOs are required to make payments to the CPPA; the CPPA, in turn, is required to pay the GENCOs (which must pay the oil-marketing companies). Thus the circular nature of these transactions.

This warped and non-transparent electricity-supply process creates opportunities for CPPA payment defaults in two very glaring ways: either (1) because the cost of providing electricity to consumers by DISCOs is not covered by operating revenues (due to rate[55] fixing and failure to adjust those rates as world oil prices fluctuate), and hence the DISCOs are unable to pay the CPPA; or (2) because the DISCOs assign a higher priority to their own cash flow instead of paying their invoices to the CPPA.[56]

The result is circular debt,[57] caused when the cash-starved CPPA is unable to pay GENCOs which, in turn, then cannot pay oil-marketing companies, which then stop future deliveries of oil, leading to power shortages. The government, then, is forced to borrow and extend additional and seemingly unending new subsidies to the GENCOs. The CCPA cash shortfall in 2012 alone amounted to nearly 4 percent of GDP.[58] In 2014, this circular debt reached almost $4 billion.[59]

In its 2014 annual report, the State Bank of Pakistan argues that the most critical bottleneck in the Pakistani electricity supply chain is created by the inefficiencies in its distribution network—specifically related to load-management, not generation. The current distribution system, in fact, cannot supply more than 15,000 MW of energy at peak demand hours. The report says: “Even if existing generating units are geared up to operate at three-fourths of their capacity, the country simply does not have the infrastructure to distribute this power to end-users.”[60]

Other inefficiencies that feed the circular debt and aggravate the energy crisis are:

- Inefficiencies of government-owned GENCOs and DISCOs; cozy deals struck with providers of rental power plants; overstaffing; free provision of electricity to public employees; poor maintenance of plant equipment; obsolete technologies (resulting in technical losses); and corruption.

- Transmission and distribution losses and poor load management.

- Massive electricity theft.

- Poor collection of electricity bills. Many powerful private individuals and companies are defaulters but are not disconnected because of their influence.[61]

- Consumption mix skewed toward less productive users where government subsidies power household consumers.[62]

Moody’s, the credit rating agency used by the IMF, has warned that Pakistan’s worsening circular debt problem will greatly affect Pakistan’s creditworthiness and cites specifically the lack of structural reform in the power-generation sector.[63]

Growth Impossible Without Deregulation of Energy Sector. At the heart of the power crisis is the government’s intransigence and insistence on retaining control of the sector. The regulatory framework permits the government to set tariffs at politically attractive but economically unsustainable low levels, thereby leading to payment defaults, circular debt, and electricity shortages. Energy-intensive companies, in turn, cannot meet production targets, and in recent years many have lost export contracts. In fact, power shortages have led many industries in Pakistan to rely on stand-by power generators, which produce electricity that is much more costly than it would be from the traditional grid source.

Although in the short run it would cause higher electricity prices, deregulation would allow generation companies to construct dedicated transmission lines to these export-oriented companies, helping them to meet demand and, in the long run, create economies of scale. The current system of unsustainably low, fixed prices only fuels corruption within the system and helps neither industry nor the consumer.

In May 2015, the IMF’s mission chief to Pakistan announced that the government and the IMF had reached an agreement to move gradually to full cost recovery in the power sector and eliminate circular debt by “increasing the allowance of losses in electricity tariff adjustments and privatization of power distribution companies.”[64]

In the past the government has repeatedly promised to tackle price distortions, inadequate collections, burdening subsidies, governance inefficiencies, and most of all, deregulation of the sector; but most of these reforms, including the privatization of most DISCOs, remain pending. Aside from some ambiguous initiatives aimed at kick-starting locally mined coal, wind, and on-grid solar power projects, the feasibility of which is still uncertain, the only progress made to resolve the crisis has been the approval of grid-connected solar energy that could be fed back to the national grid, rooftop solar installations, and mortgage financing for home solar panels, which could potentially lower the burden for domestic energy consumers. The government also eliminated a 32.5 percent tax on imports of solar equipment by private companies, in an effort to bring down the cost of installing solar panels.[65] This development, however, will neither resolve the crisis itself nor provide electricity to energy-starved industries that are growth drivers for the economy. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2014, the solar panels imported by the private sector can provide only 64.5 MW of additional energy capacity,[66] or about 1 percent of the approximately 5,000 MW energy deficit in Pakistan.

The Nawaz government had already pledged privatization of several distribution companies early on when starting his term as prime minister. Perhaps the pressure to meet targets set by the latest agreement with the IMF will push the government to take action now.

Government: No Sustainable Actions to Implement Its Economic Reform Agenda. The Pew Research Center’s 2014 Global Attitudes & Trends survey[67] showed that national priorities in Pakistan considered most troubling to the people were rising prices, electricity shortages, lack of jobs, crime, the rich/poor income gap, and corrupt political leadership. Conflict with India and terrorism in the region were of lesser concern to the average Pakistani. Although terrorist attacks, such as the horrific December 2014 attack at the school in Peshawar, cause spikes in public concern about terrorism, it is the economic condition of the country that remains paramount to Pakistanis and has become almost an existential crisis for the country.

South Asia expert Michael Kugelman of the Wilson Center asserts that Pakistan’s energy crisis is “more of a menace than militancy”[68] and says: “Pakistan’s energy insecurity is deeply destabilizing—and not just because militants prey on fragile infrastructure. Streets often swell with angry protestors railing against power outages. They have blocked roads, and attacked the homes and offices of members of Pakistan’s major political parties.”[69]

The same Pew survey indicates that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is very popular. According to the survey, 64 percent of Pakistanis had a favorable opinion of him[70] and are satisfied with the direction their country is taking under his leadership.[71]

Nawaz may have bitten off more than he can chew, however, in making sunny promises to reform the economy in order to increase his popularity. In its party platform manifesto, the Pakistan Muslim League presented a comprehensive economic agenda focusing on economic revival, energy security, and social protection, with lofty claims of doubling GDP growth (from 3 percent to 6 percent), bringing down the fiscal deficit from 8 percent to 4 percent, increasing the tax-to-GDP ratio to 15 percent, massively bringing down inflation, reducing government borrowing, minimizing power shortages, cutting import taxes, and other reforms.[72] Nawaz has repeatedly touted his belief in limited, smaller government and a free-market economy. Yet, two years into his administration, little or no progress has been seen on most of his agenda.

The political unrest, sectarian violence, and terrorism may have sidetracked the government’s attention, but do not explain its negligence in implementing reforms that are vital to reviving the economy. A joint project undertaken by a policy think tank in Islamabad, the Policy Research Institute of Market Economy, along with its international partner, the Center for International Private Enterprise, is tracking the government’s performance against its economic agenda every six months to determine where the administration stands.[73] The fourth tracking report, issued in the last quarter of 2014, calls the Pakistani government’s performance “too slow to make it.”[74] Even though the first tracking report, published in early 2014, scored the administration generously on attempting to implement some economic reforms, and indicated that the economy may be moving in the right direction, later reports continue to urge the government to take action sooner rather than later.

As of December 2014, the government, according to the tracking report, stood below 50 percent of its target goals in terms of legislative and policy developments and institutional reforms.[75] The government contended that Chinese investments of $45.6 billion for its economic corridor into Pakistan[76] would substantially relieve the energy crisis and end crippling power shortages. The project—that will create 16,000 MW of new electricity-generation capacity—will not, however, solve the larger issues of power mismanagement, poor governance and corruption within the sector, electricity thefts, and transmission losses.[77] Coincidentally, electricity shortages increased in late 2014. Other government promises were similarly found unfulfilled: No meaningful tax reforms were implemented, tax evasion persisted, and the number of tax filers actually decreased by 15,000. In efforts to reduce fiscal deficit, the government reduced budgeted power subsidies by 24 percent for FY 2015 compared to the previous year, but they remain at about 1 percent of GDP.[78]

The Economist reported in May 2015 that Pakistan was experiencing “a rare period of optimism about its economy,” citing as reasons IMF projections of 4.7 percent growth and the smallest increase in consumer prices (2.5 percent) in more than a decade.[79] Largely due to global oil price drops, Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves could experience a windfall since Pakistan’s oil imports are huge—5 percent of GDP in 2014. Such one-time gains, however, will not bolster the Pakistani economy in the long term. Deeper reforms are still essential for the economy to show sustainable signs of improvement.

In an April 2015 evaluation of Pakistan’s creditworthiness, Moody’s awarded a rating of “M–” (moderate–) for Economic Strength owing to gradual improvements. It warned, however, that the structural disabilities within the country, especially weaknesses in the power sector, could hurt this rating. In fact, the report gives a rating of “VL+” (very low+) on institutional strength and an even lower score, the lowest on the scale, “VL–,” on fiscal strength.[80]

Security Problems Undermine Economic Freedom. Political, sectarian, and religious violence, in addition to the widespread terrorist activities in the region, have played a large role in derailing the process of economic growth in Pakistan. Pakistan has witnessed countless terrorist attacks in its short history, the Peshawar attack being the most lethal. According to data compiled by the India-based Institute for Conflict Management, Pakistan has suffered over 57,000 fatalities since 2003 as a result of terrorist violence.[81]

Poor security conditions also bear some—but not all—of the blame for deterring would-be domestic and foreign investors from starting new businesses as well as discouraging existing businesses from continuing or expanding in Pakistan. Lack of security within Pakistan, whether due to terrorist attacks or violence induced by sectarian or religious attacks, often brings major cities to a halt, shuts down small and large businesses and schools, and disrupts daily life.

The Pakistani Ministry of Finance asserts that Pakistan has incurred economic costs amounting to $102 billion since 2001 due to terrorism.[82] While the Pakistani army is actively fighting the anti-government TTP militants, it is known to have a tactical approach to the terrorism ideology—fighting some while supporting others, such as the LeT or Jaish Mohammad, retaining them as strategic tools for the army’s foreign policy interests in Afghanistan and India. This has largely undermined the Pakistani state’s own efforts to eliminate terrorism in the country, bring stability, or create space for the country to grow economically.

II. The Steps to Economic Freedom

Is the News All Bad? Despite the power crisis and the current government’s lackluster performance to date, there may still be hope for Pakistan. GDP growth has had a smoother upward incline since 2008. According to a report by the State Bank of Pakistan, the contribution by the industrial and manufacturing sectors to GDP jumped significantly in 2012–2013 (by 5.4 percent) despite power shortages. Also encouraging is that 58 percent of the GDP share came from growth in services.[83]

In February 2015, the Pakistani Ministry of Textiles announced that more than 200 new textile industries were registered and, if the energy crisis were solved, production in textile products could flourish.[84] A similar outlook can be seen for other sectors of Pakistan: Growth in sectors such as paper and board, automobiles, and cement have been bogged down by energy shortages but are ripe with growth opportunities.

The IMF director for Middle East and Central Asia, Masood Ahmed, praised Pakistan for implementing some prudent monetary and fiscal policies, strengthening public finances and rebuilding foreign-exchange buffers.[85] Whereas unemployment rates remain stagnant at about 5 percent,[86] a report by the ILO revealed that job market and labor quality actually improved in Pakistan compared to countries such as India, Sri Lanka, and Mexico between 2007 and 2011.[87]

Improvement in Trade Liberalization, Opening Markets. Though barriers to trade still exist, including extensive government protection of the automotive and agriculture sectors, one of the most promising areas of growth for Pakistan is international trade. Tariffs have been slashed by half since 2002, and Pakistan has been opening its markets to greater trade opportunities. Imports tripled in the past decade. Although oil remains the top import, Pakistan now imports more machinery, electronics, vehicles, industrial inputs of plastics, metals and chemicals, and technology—all of which will spur further domestic investment and growth.[88]

According to the 2015 Doing Business report by the World Bank, Pakistan’s ranking for ease of doing business fell slightly, from 127 to 128 of 189 countries.[89] Businesses found it increasingly difficult to start a business (19 days), obtain permits (249 days), get power, or import and register property (50 days). However, the report mentions that Pakistan facilitated cross-border trade by introducing a fully automated and computerized system to process goods through customs.

Regarding intra-regional trade, Pakistan is a member of the eight-country South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), a regional economic and political cooperation group. Pakistan signed the SAARC’s South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) in 2006 with neighboring countries including India. The aim of SAFTA is an eventual regional customs union and common market but it is still not fully implemented, notwithstanding the significant yet unrealized potential for trade and investment that exists among SAARC member states.

Intra-regional trade accounts for only 4 percent of total SAARC trade, but greater regional integration and connectivity will help the SAARC countries to create new opportunities within and outside the region. Pakistan also has similar trade deals with Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia, and is in the process of signing a free trade agreement (FTA) with Turkey.[90] The government informed the National Assembly in early 2015 that a larger trade deal with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations was in the works,[91] which would open Pakistani markets to Asia’s emerging economies and create opportunities for Pakistani exports.

In 2013, the European Union granted Pakistan GSP-plus status under its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP),[92] which caused a flurry of new economic activity in Pakistan, especially in the textile sector. According to estimates by the Pakistan Business Council, the GSP-plus status would start to boost exports by $1 billion each year by 2017.[93] This boost in exports, at least in theory, could create opportunities for Pakistan to increase its market competitiveness, diversify its product mix, and in turn strengthen its industries, allowing the economy to open its markets to more sophisticated products from abroad. It remains to be seen whether the scheme will in fact provide the Pakistani economy the impetus to grow and open, since Pakistan’s manufacturing sector is still coping with electricity shortages, and may not even be able to utilize the zero-duty EU GSP preferences to its advantage. Fully one-quarter of businesses in Pakistan’s textile sector have closed recently, unable to afford the increasing cost of production that came with alternative sources of energy.[94] In addition, Pakistan faces tough competition in the European textiles and clothing markets from Bangladesh, India, China, and Turkey—all of which enjoy some form of EU preferential treatment and whose products are more competitively priced than Pakistani products.

Perhaps the most discussed FTA in Pakistani economic policy circles is the one that Pakistan signed with China in 2006, and completed the first phase of in 2013. It is currently in negotiation for a second phase in which Pakistan will reduce duties to zero on about 50 percent of Chinese products, and China will reduce tariffs to zero for 70 percent of Pakistani products immediately and 20 percent gradually over five years.[95] Pakistani domestic industries complained that cheap Chinese products flooded the markets during the initial phase of the agreement (2006 to 2013) when their own pricier products became comparatively more expensive.[96] Nevertheless, Pakistan’s exports to China still grew dramatically during the first phase, increasing from $259 million to $2.6 billion, a rate of increase relatively greater than growth of exports to other countries. Even though it is also true that more Chinese exports were coming in than Pakistani exports going out, and Chinese trade with other countries also increased, Pakistan benefitted from the higher export growth rates. Pakistan may need to negotiate an FTA with China that is amended to improve the agreement, and ask for tariff concessions for products for which it has the most competitive advantage.

Regional Cooperation: Indo-Pakistani Relationship Is Key. Regional cooperation in trade and investment offers a unique opportunity for Pakistan, given the country’s strategic location. Mostly, better trade and investment collaboration could ease some of the security and political tensions between Pakistan and its regional partners, such as India and Afghanistan. The process of Pakistan–India trade normalization, however intermittent, has at least shown some forward momentum over the years. Even though Pakistan has not granted most-favored nation (MFN)[97] status to India (notwithstanding India’s offer of MFN to Pakistan in 1996), there have been some improvements in trade between the two countries.

Despite many obstacles, bilateral trade between Pakistan and India has increased substantially in recent years. Amid military tensions at the Line of Control[98] (LoC), continued violence in Indian Kashmir (for which India blames Pakistan-backed terrorist groups), and an insurgency in Pakistan’s Balochistan province (that Islamabad claims is fueled by Indian support), trade grew from $0.3 billion in 2003 to $2.5 billion in 2014.[99] Pakistani imports from India were 84 percent of this trade in 2014 (80 percent in 2013), evidence of Pakistan’s successful attempts at opening its market. Potential bilateral trade has been estimated by the Peterson Institute for International Economics to be roughly 20 times greater than recorded trade.[100]

Nevertheless, Pakistan’s long-promised granting of MFN status to India has never materialized, largely due to various political disagreements—Kashmir being the dominant topic. For years, the two countries have insisted on mixing trade negotiations with non-trade issues, with economic cooperation halting when political tensions intensified. As a consequence, trade talks have remained intermittent. Evidently, where trade might once have paved the way to better ties with India, it now may have become a negotiating chip for resolving other, larger issues between the two countries.

Increased trade facilitation and concerted efforts on both sides to normalize trade should enable the two countries to establish some common ground and, perhaps, push contentious political issues to the back burner, at least temporarily, for the sake of regional stability. It is to be hoped that the resulting improvement in economic ties would help to thaw the cool political ties and, ideally, lead to a more productive dialogue on controversial issues.

The Transnational Strategy Group (TSG) published a study in 2014 suggesting that the two countries establish a “Special Economic Zone” in the divided Punjab region that straddles the border region between India and Pakistan. This special zone, writes Dana Marshalls, president of TSG, could facilitate trade by removing some cross-border obstacles to doing business.[101]

The first step for an improved trading environment must be the granting of MFN status by Pakistan to India. This would facilitate cross-border trade and benefit both sides in the long run. According to estimates by the Sustainability Development Policy Institute, total actual trade (in the formal and informal economies) between Pakistan and India is almost double the official figures, with Indian exports to Pakistan that arrive via third countries, such as Dubai, amounting to $1.79 billion each year.[102] MFN status would enable direct imports into Pakistan from India instead of the indirect routes that are more expensive because of higher transport costs, and thus ultimately benefit the Pakistani consumer.

MFN status would also provide a healthy dose of competition for local producers in the automotive, agriculture, pharmaceutical, and textile sectors that have, for years, enjoyed extensive tariff protection from the government at the expense of Pakistani consumers. Continued protection will only further damage Pakistan’s economy, already burdened by inefficient producers and costly products.

Pakistan and India together must fully ratify SAFTA; open their markets and borders to facilitate low-cost trade; decrease overall tariffs for all eight South Asian countries under the agreement; categorically remove the many physical barriers (such as inefficiencies at the border for transport and transit, difficulties in custom procedures, complex visa regimes, operational, infrastructural and banking constraints); and eliminate the unyielding, bureaucracy-based, non-tariff barriers that have hindered trade, specifically on the Indian side of the border. As part of its counterterrorism efforts in South Asia, the U.S. government should encourage economic cooperation between the two countries, which would stabilize the region.

Chinese Investments and Other Infrastructure Projects. Pakistan’s geopolitical location gives it a large advantage in terms of connectivity and economic integration. It is at the center of three important regions of the world—the Middle East, South Asia, and Central Asia—and shares borders with Asia’s growing economies, such as India and China. The Chinese government realizes this fact and has stayed at the epicenter of Pakistan’s foreign policy providing military and economic assistance over the years.

Pivotal to China’s “Silk Road Economic Belt” strategy is the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC),[103] potentially worth $45.6 billion, which would drive an overhaul of infrastructure[104] including roads, highways and a network of oil and gas pipelines that would help to alleviate Pakistan’s chronic energy shortages. It could also create greater trade opportunities in the region.[105] The corridor, according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry, will “serve as a driver for connectivity between South Asia and East Asia,”[106] and will not only help Pakistan in terms of infrastructure investment but also serve China’s larger interests of connecting with Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. How much of this investment eventually materializes depends strongly on Pakistan’s political stability, how the government curtails public-sector corruption, and also on China’s motivations to see the project through. China may be the “friendliest” partner for Pakistan currently, but it is not the most reliable. According to a 2013 RAND study, of the total $66 billion in financial assistance that China pledged to Pakistan between 2001 and 2011, only 6 percent has actually been delivered.[107] Perhaps that is because, as Pakistani Federal Minister Ahsan Iqbal has said: “CPEC is the shortest but not the only supply chain route for China.”[108]

Pakistan is also in the process of finalizing the Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India (TAPI) gas pipeline and CASA 1000, an energy gas-transfer project equating to 1,000 MW of additional capacity from Central Asia to Afghanistan and Pakistan. According to April 2015 Pakistani news reports, the Minister for Water and Power in Pakistan was confident that through the TAPI pipeline and other projects the government is undertaking, the energy crisis would be resolved by the end of 2017.[109] As lofty and unrealistic as these claims might appear, Pakistan is going in the right direction in terms of strengthening relations with its regional partners and optimizing its regional importance.

III. What Pakistan’s Government Can—and Should—Do

As detailed in this Special Report, major improvements to Pakistan’s economic policies are needed in many different areas. Most essentially, however, the Pakistani government must introduce immediate and forceful reforms on three crucial fronts to revive the economy. The government should:

- Deregulate the energy industry. The government should reduce energy subsidies and deregulate all distribution and power generation companies so that the sector can unleash market forces to more efficiently determine electricity rates. This would allow for greater investments and resolve the structural issues in the power sector, including distribution inefficiencies and circular debt. Privatization would also curb corruption within the system. It would enable energy agencies to work autonomously when collecting electricity bills and holding customers accountable for non-payment and theft.

- Decrease dependence on foreign debt. Pakistan must decrease its reliance on foreign funding by categorically reducing government spending and increasing revenues. This should be done by introducing substantive tax reforms that broaden the tax base, bring the entire population and the informal business sector into the tax system, eliminate all exemptions and privileges to certain individuals or organizations, decrease tax evasion through tougher enforcement, and document the existence of economic activity with a major overhaul to the government’s information technology infrastructure.

- Curtail widespread corruption. Cutting red tape, removing needless regulations, and increasing accountability are integral to resolving corruption in Pakistan. The National Accountability Bureau (NAB—similar to the U.S. Government Accountability Office), the executive-level and independent government entity that monitors the accountability and transparency of all Pakistani state institutions, should be empowered (including necessary security measures) to scrutinize and report cases impartially—without fear of retribution. The government should not interfere in the scope, operations, or jurisdiction of the NAB, or in any other anti-corruption agencies, including the judiciary. Right-to-information laws[111] should be introduced so that citizens can scrutinize government activities and ensure the proper stewardship of all public resources.

Ultimately, privatization would also eliminate Pakistan’s “circular debt” power- generation-financing problem and, thereby, lessen the need for future major government borrowings that have burdened the economy in the past.

The government should also diversify Pakistan’s energy mix in order to decrease reliance on imported fuel and increase self-sufficiency in indigenous resources, such as coal, wind, biomass, solar, and hydroelectricity.[110] At the same time, Pakistan should welcome foreign investment to develop all of Pakistan’s natural energy resources.

Of course, the highest-priority reform for Pakistan’s fiscal and monetary apparatus must be to make the State Bank of Pakistan (the central bank) fully independent so that it can manage foreign reserves more transparently and professionally.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding a modest uptick in Pakistan’s economic freedom in recent years, there are still far too many Pakistanis living in repressive poverty and surviving only on subsistence agriculture in the country’s large informal economy. It has been politically expedient, but wrong, for Pakistan’s civilian government to blame this lack of economic progress entirely on the nation’s difficult security situation, when, in fact, it is largely the lack of sustained reforms that has hindered growth. Massive public-sector corruption; the over-regulation, inefficiency, and fiscal unsustainability of state-owned energy and power services; protectionist trade and investment regimes; and the lack of decisive reforms in the tax system are the challenges that the government must address. It should address them now.

—James M. Roberts is Research Fellow for Economic Freedom and Growth in the Center for Trade and Economics, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation. Huma Sattar is the Atlas Corps—CIPE Fellow and a Visiting Scholar at The Heritage Foundation.