and International Organizations

My name is Brett Schaefer. I am the Jay Kingham Research Fellow in International Regulatory Affairs at The Heritage Foundation. The views I express in this written submission are my own and should not be construed as representing any official position of The Heritage Foundation.

I appreciate the opportunity to submit this written statement in conjunction with the hearing titled, UN Peacekeeping Operations in Africa, before the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. While the witnesses will be discussing challenges facing United Nations peacekeeping operations in Africa, I believe that the members of the committee would benefit from a brief overview of financing for peacekeeping operations.

History of the Scale of Assessments

The United Nations Charter does not specify a method for paying for the expenses of the organization even though the U.S. was concerned about shouldering an excessive portion of the funding even in the early negotiations to establish the U.N.REF The Charter, completed at the 1945 San Francisco conference, references budgetary procedures only in Articles 17, 18, and 19.

- Article 17 states: “The General Assembly shall consider and approve the budget of the Organization” and that the “expenses of the Organization shall be borne by the Members as apportioned by the General Assembly.”

- Article 18 states that each member state has one vote, and that important matters, including budgetary questions, require approval “by a two-thirds majority of the members present and voting.”

- Article 19 stipulates that any member state “in arrears in the payment of its financial contributions to the Organization shall have no vote in the General Assembly if the amount of its arrears equals or exceeds the amount of the contributions due from it for the preceding two full years” unless the General Assembly “is satisfied that the failure to pay is due to conditions beyond the control of the Member.”REF

The lack of detail on financial contributions was deliberate. In the words of the Venezuelan delegate to the San Francisco conference, how the U.N. should be funded was “one of the most delicate and debated questions” and was avoided out of concern that it could undermine the delicate negotiations underway.REF Avoiding the issue facilitated negotiations in 1945, but laid the groundwork for repeated budgetary clashes with the U.S.

Since the U.N.’s establishment, its member states agreed to apportion its expenses “broadly according to capacity to pay.”REF This means that wealthier nations, based principally on per capita income, pay larger shares of the budget than poorer nations. The United States has been the U.N.’s largest financial supporter ever since the organization’s founding and was assessed 39.89 percent in the first scale adopted in 1946.REF Even in 1946, however, the U.S. strongly objected to paying more than 25 percent of the expenses of the U.N. and sought consistently in subsequent decades to reduce the U.S. assessment.REF

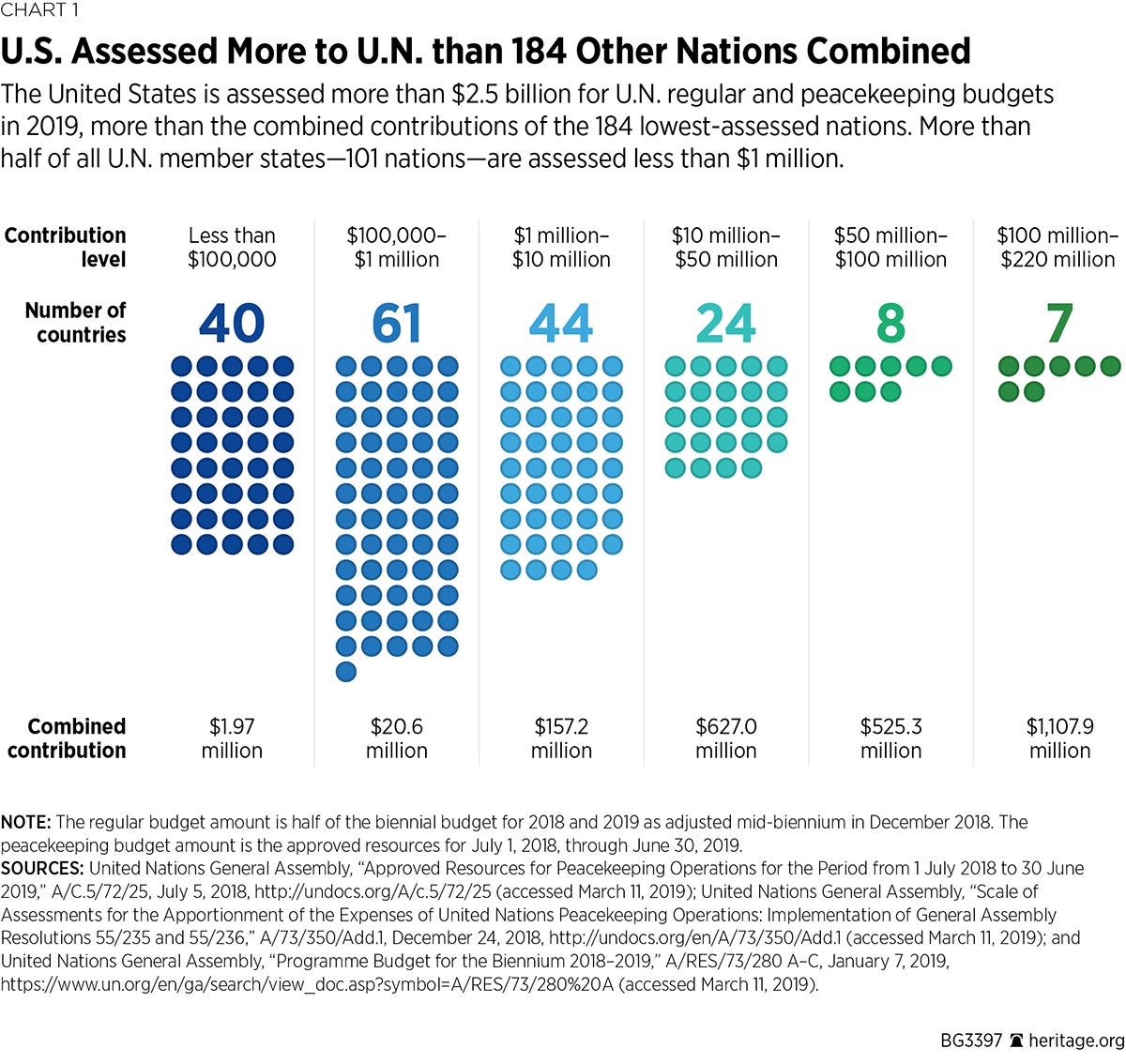

The U.S. sought to more equitably distribute the costs of the U.N. for several reasons. As the financial burden of U.N. budgets increased, the desire to reduce the cost for U.S. taxpayers has risen as a motivation. Indeed, when the U.S. pays more than 184 nations combined, it is hardly shocking that the U.S. would like other nations to assume a larger share of the cost of the U.N.

However, this was not and is not the sole motive. From the beginning, the U.S. maintained that relying too heavily on one country would distort incentives within the organization and undermine “the sovereign equality of nations.”REF The historical struggle of the U.S. to improve U.N. oversight and accountability, and focus resources on high-priority, effective activities—instead of outdated, duplicative, or unproductive activities—illustrates the prescience of this concern.

Indeed, as evidenced by their actions in establishing a minimum assessment of 0.04 percent in 1946, the founders of the U.N. did not believe that membership should be costless or insignificant, even though the original member states included extremely poor countries, such as Liberia. Over the past six decades, however, the regular budget assessments provided by poor or small U.N. member states have steadily ratcheted downward.REF

Adjusting for inflation, a country with the minimum assessment is charged far less in real terms in 2019 than it was charged 70 years ago. For instance, the General Assembly approved $47.8 million for the expenses of the organization for 1951.REF Adjusting for inflation, this would be $467.3 million in 2019. Thus, with a 0.04 percent assessment in 1951, Liberia was expected to pay the 2019 equivalent of $187,000—more than five times the amount it will be assessed for both the regular and peacekeeping U.N. budgets in 2019.

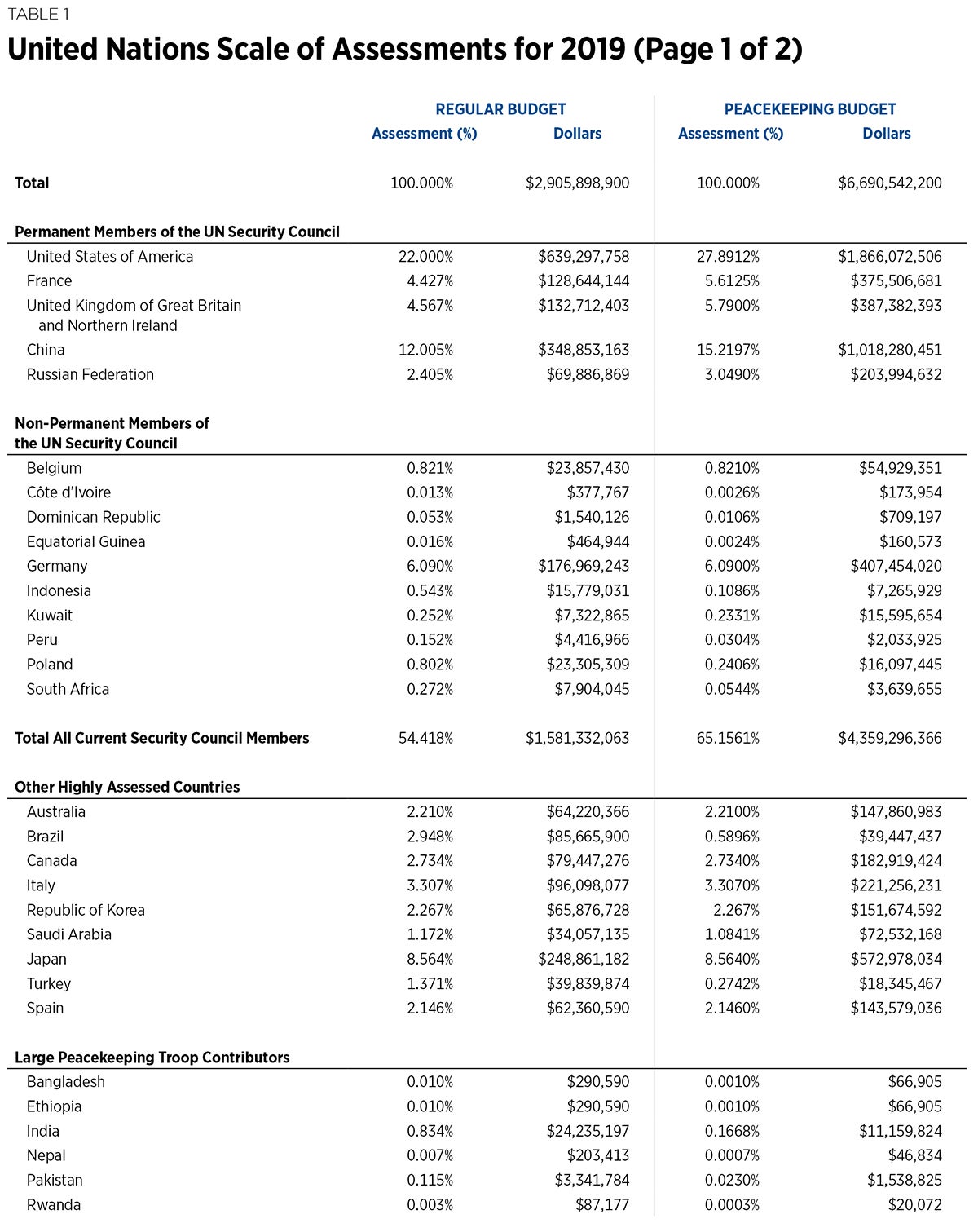

The adjustments to the scale over the years has sharply increased the disparity of the financial burden between the member states. Under the current scale, the top 10 contributors are assessed more than 69 percent of the U.N. regular budget and over 80 percent of the peacekeeping budget.

U.N. Regular Budget Scale of Assessments

The current scale of assessments for the U.N. regular budget, which covers the expenses of the Secretariat, the General Assembly, and other U.N. bodies, uses the methodology agreed to in 2001.REF The calculation of assessments starts with a country’s gross national income (GNI) converted into U.S. dollars according to market exchange rates.

For countries under a specified income threshold, the U.N. adjusts the income data downward by 12.5 percent of the country’s debt burden (the theoretical debt-service ratio). In addition, countries with low per capita incomes, defined as under the world average for the period, have their incomes further reduced by 80 percent of the difference between a country’s per capita GNI (PCGNI) and the world average. The methodology distributes the cost of the debt and low per capita income adjustments on a proportional basis among the member states that do not qualify for those reductions.

Finally, the scale incorporates a maximum assessment of 0.01 percent for “least developed countries” and, for all countries, a minimum assessment of 0.001 percent and a maximum assessment of 22 percent. The methodology distributes the cost of these minimum and maximum assessments on a proportional basis among the member states that do not qualify for those adjustments. The resulting adjusted income over two periods (the preceding six years and preceding three years) are used to derive the final assessments.REF

All told, approximately two-thirds of the 193 U.N. member states receive some sort of reduction to their regular budget assessment through various adjustments—in other words, their assessment is less than their share of world GNI.REF

U.N. Peacekeeping Budget Scale of Assessments

The current scale of assessments for the U.N. peacekeeping budget uses the methodology agreed to in 2001. Under this methodology, the peacekeeping assessment rate uses the regular budget as its starting point and divides the U.N. member states into 10 levels based on (1) permanent membership on the Security Council and (2) their PCGNI.REF

- Permanent members of the Security Council, placed in “Level A,” are assessed at a higher rate than their regular budget assessments. This surcharge, called a “premium,” is the total amount of the peacekeeping discounts awarded to other member states in Levels C through J and is distributed on a pro rata basis among the five permanent members.

- Most countries with a PCGNI higher than twice the average for all U.N. member states are placed in “Level B” and receive no discount off their regular budget assessment, that is, they are assessed the same percentage for the regular budget and the peacekeeping budget.

- A small number of countries—currently Brunei Darussalam, Kuwait, Qatar, Singapore, and the United Arab Emirates in the 2019–2021 scale of assessments—with a PCGNI above twice the world average are placed in “Level C” and receive a 7.5 percent discount. This discount is awarded because they are members of the Group of 77 and are considered “developing countries” even though their PCGNIs are higher than about a third of the countries in “Level B.”

- All countries at or below twice the average world PCGNI are placed in “Level D” through “Level I” and receive discounts between 20 percent and 80 percent off their regular budget assessment. The discounts increase as PCGNI falls below specified thresholds.

- Finally, all countries considered “least developed countries” are in “Level J” and receive a discount of 90 percent off their regular budget assessment.

Over 80 percent of all U.N. member states receive some sort of discount on their peacekeeping assessment. These discounts apply in addition to any regular budget discounts they receive. Overall, discounts applied for the peacekeeping scale of assessments totaled 12.1583 percentage points in 2019 ($813.5 million under the current peacekeeping budget),REF which the permanent members of the Security Council shoulder as the premium surcharge.REF

Disparities in U.N. Assessments

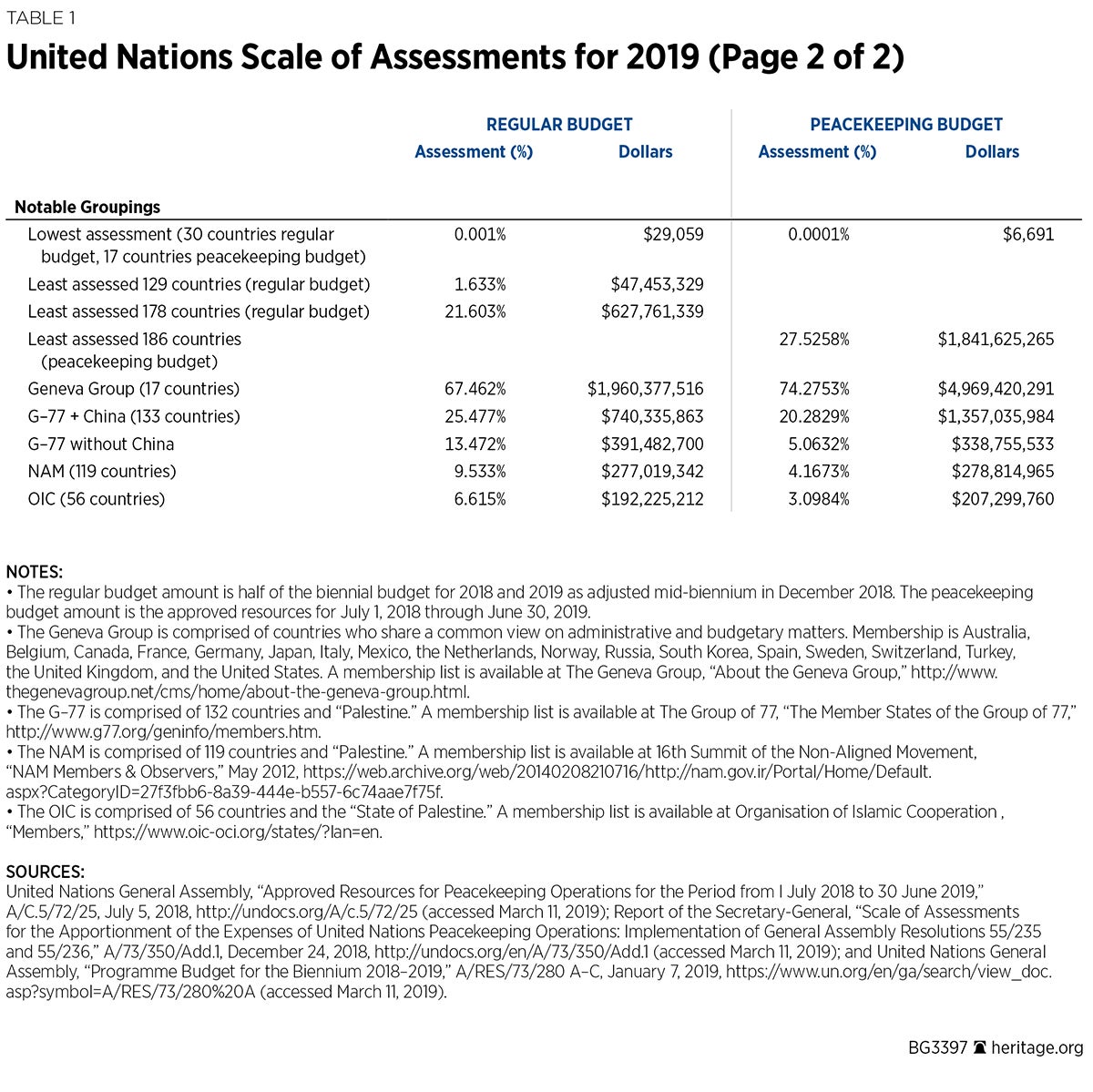

The primary result of assessment adjustments has been to shift the costs of the organization away from the bulk of the membership onto a relative handful of high-income nations. The U.S. is the highest assessed country and is charged 27.8912 percent of the peacekeeping budget in 2019. In dollar terms, this equates to $1.866 billion for the current U.N. peacekeeping budget. As illustrated in the Table:

- The U.S. is assessed more than 186 other countries combined and 280,000 times more than the least-assessed countries.

- Under the current peacekeeping scale of assessment, the 17 countries paying the minimum peacekeeping assessment of 0.0001 percent each will be assessed approximately $6,691 based on the approved peacekeeping budget for 2018–2019. The standard reimbursement to countries for uniformed personnel deployed on U.N. peacekeeping operations is $1,428 per soldier per month.REF This means that the yearly peacekeeping assessment of the least assessed member states covers less than five months of the cost of one U.N. peacekeeper.

- The U.N. will assess 78 of 193 U.N. member states less than $100,000 this year for peacekeeping and 120 out of 193 member states will be charged less than $1 million this year for U.N. peacekeeping.

This imbalance is long-standing, but was tolerable when the cost of peacekeeping was minimal as was the case during the Cold War when operations tended to be relatively small and rare and expenditures similarly constrained. However, spiraling costs of peacekeeping in the early 1990s led Congress to cap unilaterally U.S. payments for U.N. peacekeeping at 25 percent of the budget. The resulting arrears put stress on the organization, but created incentives for the other member states to agree to a number of reforms in return for payment, including agreeing to adopt the current methodology for peacekeeping assessments that was projected to lower the U.S. share to 25 percent as required by U.S. law.REF

Unfortunately, the U.S. share of the peacekeeping budget never fell to 25 percent as projected. The difference between 25 percent and what the U.N. charges the U.S. may seem small, but it costs American taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

The U.S. share of the peacekeeping budget in currently 27.8912 percent and Congress has stopped overriding the 25 percent cap on payments for peacekeeping. As a result, the U.S. has again been accruing arrears. Although the U.S. currently has the largest amount of arrears, it is hardly the only nation in arrears currently nor was it the first nation to withhold funding to the U.N.

In fact, the willingness of the U.S. to withhold U.N. funding dates back to a dispute over two peacekeeping operations in the late 1950s and early 1960s (ONUC and UNEF I) to which the Soviet Union, France, and dozens of other nations withheld payment for political reasons. Tens of millions of dollars in assessments for these missions remain in arrears and are considered to be unpaid contributions, but were placed in a special account and are not included in calculations for Article 19 purposes.REF

While accepting this arrangement, the U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations at the time, former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States Arthur Goldberg, stated:

[I]f any Member can insist on making an exception to the principle of collective financial responsibility with respect to certain activities of the organization, the United States reserves the same option to make exceptions to the principles of collective financial responsibility if, in our view, strong and compelling reasons exist for doing so. There can be no double standard among the members of the organization.REF

In other words, once other member states established precedent for withholding funding to the U.N., the U.S. made clear that it would in the future be justified in withholding from the U.N. for reasons it found reasonable.

Reapplying Past Lessons

While the U.S. is a powerful and influential nation, in the U.N. it is only one of 193 member states. The U.N. scale of assessments is a zero-sum game. In order for the U.S. assessment to fall, the assessments for other countries must rise. Negotiating the previous reduction in the U.S. assessment took years of skillful, tough diplomatic negotiations led by Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, backed by the financial pressure of nearly $1 billion in U.S. arrears. In good faith, the U.S. paid the arrears that had accrued in expectation that the U.S. peacekeeping assessment would fall to 25 percent. Unfortunately, that never happened.

Reducing the U.S. peacekeeping assessment to 25 percent will require similar effort over the next three years. As occurred in the 1990s, the U.S. should continue to use its financial leverage and withhold the difference between its peacekeeping assessment and the 25 percent cap enacted under U.S. law until the U.N. implements a maximum peacekeeping assessment of 25 percent. To avoid a repetition of the Helms–Biden disappointment, the U.S. should pay these arrears only after the U.N. incorporates a maximum assessment of 25 percent in the methodology for calculating the peacekeeping scales of assessment.

While this will create short-term financial hardship for U.N. peacekeeping, a more equitable distribution of peacekeeping assessments will benefit the U.N. in the long term and ease the burden on U.S. taxpayers. Peacekeeping benefits all U.N. member states and it is entirely reasonable for the U.S. to call on non-permanent members of the Security Council—whose support is necessary to approve peacekeeping operations—as well as upper-middle-income and high-income countries that have the capacity to pay more and forego peacekeeping assessment discounts.

Conclusion

The negotiators in 1945 did not wish U.N. membership to cause financial hardship, but also recognized that divorcing the costs of the organization from the privileges of membership would create perverse incentives among the member states. The historical struggle of the U.S. to constrain growth in U.N. budgets, improve accountability and oversight, and focus resources on high-priority, effective activities—instead of outdated, duplicative, or unproductive activities—illustrates the prescience of this concern.

To resist this outcome, the U.S. since the founding of the U.N. has argued for a maximum assessment level and, subsequently, for lowering that maximum. In 2001, the U.S. succeeded through use of financial withholding and diplomacy to get the U.N. to adopt a maximum assessment of 22 percent for the U.N. regular budget. Unfortunately, the U.S. was not able to get the U.N. member states to agree to a maximum peacekeeping assessment of 25 percent. This failure has cost U.S. taxpayers well over two billion dollars.

Two decades later, it is time for the U.S. to address this matter. U.N. revenues are at record levels and the demands for finite resources is increasing.REF The U.S. is and always has been the largest financial supporter of the U.N. and should continue to fulfill that leadership role. However, the U.N. would be healthier, and more member states would have an incentive to scrutinize the budget to maximize efficiency and focus resources on priorities, if the costs were more equitably distributed.

*******************

The Heritage Foundation is a public policy, research, and educational organization recognized as exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. It is privately supported and receives no funds from any government at any level, nor does it perform any government or other contract work.

The Heritage Foundation is the most broadly supported think tank in the United States. During 2018, it had hundreds of thousands of individual, foundation, and corporate supporters representing every state in the U.S. Its 2018 operating income came from the following sources:

Individuals 67%

Foundations 13%

Corporations 2%

Program revenue and other income 18%

The top five corporate givers provided The Heritage Foundation with 1% of its 2018 income. The Heritage Foundation’s books are audited annually by the national accounting firm of RSM US, LLP.