The Not-So-Great Society

Click here to view the full page.

Classroom Content: A Conservative Conundrum

Robert Pondiscio

The content of K–12 education is a minefield for conservatives. Over the past 30 years, education reformers who wanted parents to have choices for their children have tended to focus more on the creation of new public charter schools, or on private school scholarships, than on curriculum and classroom content. They have placed their faith in school choice and the market to create demand for a rich, well-rounded education: Let parents choose and the market provide, and may the best curriculum win.

That faith is largely misplaced. Nearly all—90 percent—of K–12 students in the U.S. attend public schools, including public charter schools and magnet schools, with most students (71 percent) attending the school to which they are assigned based on their ZIP code.1 Parents and policymakers should also not assume that schools of choice are automatically more sophisticated about curricular content (some are; many are not). There is a foreseeable price to be paid for the reluctance to engage on the foundational question of what the 45 million public school children across the country should know, and leaving it to chance or whim. Doing so risks abandoning the next generation to semi-literacy and, therefore, less than full citizenship. The content delivered in classrooms across the country is a matter that conservatives should not abandon to the Left.

Education should ensure that children grow up to be fully literate, and it should equip students with the necessary tools for becoming responsible citizens. This is a point that E. D. Hirsch Jr., whose work is a focus of this chapter, has stressed throughout his career. But, as Hirsch explained in his landmark 1987 book Cultural Literacy, America’s elementary schools have come to be “dominated by the content-neutral ideas of Rousseau and Dewey.”2 At the time, 16,000 independent school districts represented “an insurmountable obstacle” to renewal. “We have permitted school policies that have shrunk the body of information that Americans share, and these policies have caused our national literacy to decline,” Hirsch wrote.3

What options do conservatives have for addressing inadequate academic content? An incoherent skills-driven vision of curricula, vacuous and ineffective, has dominated American education for a half-century or more. Textbook battles have tended to end badly for conservatives, as opponents claim that instruction based on classic texts whitewashes American history.4

Parental choice in education should remain at the heart of conservative public policy. Still, attention must be paid to the content taught in public schools. As William J. Bennett observed, “[I]t would be intellectually dishonest to not recognize the limitations of choice, given that more than four in five students attend a traditional neighborhood public school and the exercise of choice requires parents who will participate and teachers and schools that teach well.”5 In sum, what children learn in school matters. Instructional content is a critical component of basic literacy, and advances (or fails to advance) the fundamental civic mission of schools in fostering thoughtful and engaged citizenship.

Education choice leads to different governance models and has created curricular diversity in some, but not all, cases. The traditional district-based school system has been slower to adjust. The high-quality content that has blossomed in some choice networks (see, for example, Robert Jackson’s chapter in this book on the Great Books curriculum used in the Great Hearts charter school network) has not propagated across district schools due in large part to schools of education, school board associations, and other interest groups that vie for power and to influence or control what children learn.

The path leading to this conservative conundrum on curriculum is instructive. Hirsch’s Cultural Literacy made the unimpeachable case that schools were systematically denying American children the knowledge they needed to function as fully literate members of civil society. “We Americans have long accepted literacy as a paramount aim of schooling, but only recently have some of us who have done research in the field begun to realize that literacy is far more than a skill and that it requires large amounts of specific information,” he wrote. Hirsch subsequently described how he was “shocked into school reform”6 while conducting research on reading ability at a Richmond, Virginia, community college. He discovered that the community college students could read just as well as the undergraduates at Hirsch’s own University of Virginia when texts were about everyday topics, such as car traffic or roommates, but when required to read, for example, about the U.S. Civil War, their reading comprehension fell apart. “They had not been taught the things they needed to know to understand texts addressed to a general audience. What had the schools been doing?” he wondered.7

Hirsch’s basic insight, consistently validated by cognitive science, is that a student’s ability to comprehend a text is largely determined by the student’s background knowledge.8 Speakers and writers make assumptions about what readers and listeners know, and rely on them to understand references and allusions, and to make correct assumptions about word meanings and context. For example, even the simple word “shot” means different things in a bar, a rifle range, a basketball court, or when the repairman uses it to describe one’s refrigerator. If readers cannot supply the missing information or make correct assumptions about context, comprehension suffers. A piece of text is like a child’s game of Jenga, where every block is a piece of background knowledge or vocabulary. When just a few are missing, the tower of blocks still stands. Pull out one too many, and it collapses.

Hirsch attempted to catalogue much of this assumed knowledge with a list of 5,000 “essential names, phrases, dates, and concepts,” ranging from Biblical references and Greek myths to basic scientific concepts and key figures in history, which drove Cultural Literacy to the top of best-seller lists.9 Most Americans likely assume that their children are getting what Hirsch is prescribing: a well-rounded elementary and middle-school curriculum, rich in literature, history, geography, science, and the arts that would endow them with the basic assortment of mental furniture—general knowledge, allusions, and idioms—that educated Americans take for granted.

A man of the Left who has described himself “practically a socialist,” Hirsch was widely criticized, even reviled in some quarters, for what many perceived as an effort to enshrine a dead, white male canon, and to impose conservative views of “What Every American Needs to Know” (as the subtitle of Cultural Literacy puts it) on U.S. education.10 But Hirsch’s project was and remains a curatorial effort aimed at explaining—and rescuing—reading comprehension. This fundamental disconnect led University of Virginia professor of psychology Daniel Willingham to describe Cultural Literacy as “possibly the most misunderstood education book of the last fifty years.”11

Crucially, the America in which Cultural Literacy was first published was one in which charter schools did not yet exist, and where private school choice existed mostly in Milton Friedman’s head. Thus leading conservatives in education, such as President Ronald Reagan’s Education Secretary William Bennett and Chester Finn and (erstwhile conservative) Diane Ravitch (authors of What Do Our 17-Year-Olds Know? also published in 1987), were more apt and eager to battle it out over the curricular content of children’s education. Those three were among Hirsch’s earliest and most vocal champions, eagerly taking up his call to transform the content of the curriculum in public schools since few, if any, alternatives existed.

There is far less appetite among conservatives today for battles over curricula, whether because of evolving theories of educational change (read: increased choice), practical politics, or concern about encroachment into local school autonomy. The past decade’s battles over Common Core suggest that conservatives have little appetite for large-scale standards-based initiatives with federal financial backing. Hirsch, meanwhile, has enjoyed at least something of a reappraisal (if for no other reason than the general absence of improved reading scores in the decades since choice began to flower), and a muscular test-driven accountability regime has come to dominate American education. His broad general thesis—knowledge matters—if not his precise prescription, was embedded (and almost entirely overlooked) in the Common Core standards for English Language Arts, which advised:

By reading texts in history/social studies, science, and other disciplines, students build a foundation of knowledge in these fields that will also give them the background to be better readers in all content areas. Students can only gain this foundation when the curriculum is intentionally and coherently structured to develop rich content knowledge within and across grades.12

This recommendation might have been expected to resonate with conservatives and ought to have been taken up vigorously. But Common Core or no Common Core, the wisdom of the passage above remains. It can be summarized with just three words: Hirsch was right.

More than 30 years after Cultural Literacy appeared, the opportunity for conservatives to use Common Core to re-engage on curricular content has largely been lost. The failure of schools to “fulfill their acculturative responsibility” that Hirsch observed remains the default condition in American education, reflected in the experience of the vast majority of American children. And where conservatives have grown wary and suspicious of meddling in curricula, activists and advocates on the Left have demonstrated far less reticence about imposing their views, moving further from the unifying impulse undergirding the entire purpose of public education. It is only a mild overstatement to say that the vast majority of current thought in education practice and policy—from personalized learning to “culturally relevant pedagogy”—reflects an assumption that curricular content should not just reflect, but be grounded in, children’s personal interests and experience. This notion drifts ever further from the common school ideal of American public education, and does ever further violence to basic literacy. There remains a profound risk that abandoning efforts within the public system to ensure equal access to common knowledge, even in the laudable service of honoring educational pluralism, will further estrange Americans from one another, deepening social, cultural, and political divisions. What is taught in the nearly 100,000 public schools across the country should be a matter of grave concern to conservatives.

The conservative project for school curriculum extends from the founding (and largely forgotten) purpose of public education: preparing each generation of children for engaged and responsible citizenship. Civic education—once the founding purpose of American education—has been marginalized, particularly in the education-reform era. The thrust of school improvement efforts has been raising reading and math scores, inevitably marginalizing other content areas, and none more so than civics. Indeed, compared to student achievement in civics and history measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, reading performance in U.S. schools, generally viewed with alarm, is downright robust.13 Here again, Hirsch is the indispensable theorist. His 2009 book The Making of Americans traced the history and purpose of the American common school: “The center of its emphasis was to be common knowledge, virtue, skill, and an allegiance to the larger community shared by all children no matter what their origin.”14

To state the matter mildly, the goal of fostering “allegiance to the larger community” is no longer anywhere near the heart of American education. This allegiance is in danger of being abandoned altogether, even as an aspiration. The same dynamic that has fatally damaged literacy for untold numbers of American children is playing out again in civic education, and the same mistake—valorizing vague skills over educational content, and blithely dismissing what should be common knowledge as “mere facts”—is readily observable.

A quiet revolution in civics education has been gaining ground in recent years, emphasizing student “voice” and “agency,” as well as direct participation in public affairs, politics, and protest. Where civics education has historically concerned itself with ensuring that students know how a bill becomes law, “action civics” seeks to close a “civic empowerment gap” and to reverse the “marginalization of youth voice.”15 Students routinely participate in rallies and demonstrations on controversial issues, such as climate change and gun control. Schools and districts seem less likely to be concerned with presenting a balanced view of contemporary controversies than whether students should be held accountable for skipping class to participate.16 The common impulse, well-intended if misguided, is to “support” and celebrate student activism.

Yuval Levin has observed that “conservatives tend to begin from gratitude for what is good and what works in our society and then strive to build on it, while liberals tend to begin from outrage at what is bad and broken and seek to uproot it.”17 A critical function of American K–12 education is citizen-making and fostering the ability to contribute productively in the public sphere. It cannot be sensibly denied that “action civics” by definition focuses students’ attention on the bad and the broken, not on gratitude for what is good and what works. The omission is as harmful to citizen-making as the lack of common content is to basic literacy.

In a recent paper for the Hoover Institution, William Bennett, one of Hirsch’s earliest champions, observed how “the lack of conservative consensus on content has very real and very negative consequences.”18 More ominously, Bennett concluded, “the vacuum cedes the field to the other side, who knows very well what it intends to do.”19 Conservatives can no longer stand on the sidelines of debates about the foundational question of what children in public schools across the country should learn. They risk leaving the next generation semiliterate and ill equipped for participating in—and simply maintaining—a civil society. For that reason, school choice must be pursued in conjunction with reforms to improve content and curricula in public schools across the country.

REFERENCES

- National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, 2018, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_206.30.asp (accessed August 5, 2019).

- E. D. Hirsch Jr., Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1987).

- Ibid.

- “How Texas Is Whitewashing Civil War History,” The Washington Post, July 6, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/whitewashing-civil-war-history-for-young-minds/2015/07/06/1168226c-2415-11e5-b77f-eb13a215f593_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.bfac6d06f451 (accessed August 5, 2019).

- “Education 20/20 Speaker Series: William Bennett,” Hoover Institution, June 13, 2019, https://www.hoover.org/events/education-2020-speaker-series-william-bennett (accessed August 5, 2019).

- E. D. Hirsch Jr., “Creating a Curriculum for the American People: Our Democracy Depends on Shared Knowledge,” American Educator (Winter 2009–2010), pp. 6–38, https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/hirsch.pdf (accessed August 5, 2019).

- Ibid.

- Daniel T. Willingham, “How Knowledge Helps,” American Educator (Spring 2006), https://www.aft.org/periodical/american-educator/spring-2006/how-knowledge-helps (accessed August 5, 2019).

- Current versions are titled A Dictionary of Cultural Literacy.

- Peg Tyre, “‘I’ve Been a Pariah for So Long,’” Politico Magazine (September/October 2014), https://www.politico.com/magazine/politico50/2014/ive-been-a-pariah-for-so-long.html#.XSoJjutKiM9 (accessed August 5, 2019).

- E. D. Hirsch Jr., “Romancing the Child: Curing American Education of Its Enduring Belief that Learning Is Natural,” in Chester E. Finn Jr., and Michael J. Petrilli, eds., Knowledge at the Core: Don Hirsch, Core Knowledge, and the Future of the Common Core (Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2014), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED559999.pdf (accessed August 5, 2019).

- Common Core State Standards Initiative, “English Language Arts Standards–Anchor Standards–College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading,” http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/R/ (accessed August 5, 2019).

- The Nation’s Report Card, “2014 Civics Assessment,” https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/hgc_2014/#civics (accessed August 5, 2019).

- E. D. Hirsch Jr., The Making of Americans: Democracy and Our Schools (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 8.

- National Action Civics Collaborative, “Action Civics Theory of Change,” http://actioncivicscollaborative.org/why-action-civics/theory-of-change/ (accessed August 5, 2019).

- Melissa Korn and Leslie Brody, “Some Students Face Consequences to Walk Out,” The Wall Street Journal, March 14, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/some-students-face-consequences-to-walk-out-1521057082 (accessed August 5, 2019).

- Yuval Levin, “Conservatism Is Gratitude,” Ethics and Public Policy Center Bradley Prize Remarks, June 12, 2013, https://eppc.org/publications/conservatism-is-gratitude/ (accessed August 5, 2019).

- “Education 20/20 Speaker Series: William Bennett,” Hoover Institution.

- . Ibid.

The Classical Charter School Movement: Recovering the Social Capital of K-12 Schools

Robert Jackson, PhD

When principal investigator James Coleman delivered the of the federally funded Equality of Educational study in 1966, later known simply as the Coleman Report, he brought unexpected news to Congress: In spite of segregation, school funding was near parity among schools within regions, and family background and socioeconomic diversity within the classroom were the primary factors affecting a student’s academic performance.1

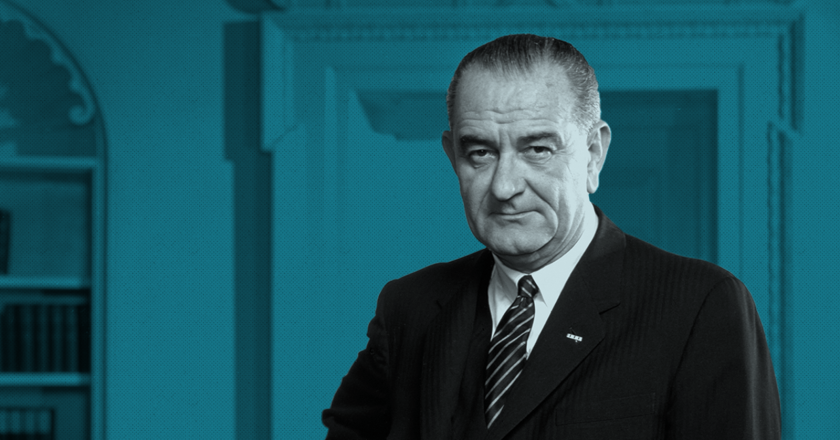

A centerpiece of the War on Poverty, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s educational reforms were contained in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, with a special focus on funding schools with disproportionate numbers of low-income, often non-white, students. With federal support for the research, the Coleman Report became the largest sociological study at that time of American public education, with more than 600,000 surveys taken from 4,000 schools—and one of the largest studies of this type ever conducted.2 Coleman’s team of social scientists was given the mandate to evaluate the efficacy of educational programs based on funding and other demographic variables. The Johnson Administration intended to empirically demonstrate the need for greater equality of opportunity for all students, an essential pillar of the President’s domestic agenda, as outlined in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Coleman was the first to statistically document an achievement gap between African American children and their white counterparts. However, the report’s findings surprised lawmakers by pointing beyond the amount of money spent on K–12 education to the characteristics of schools that produced greater academic performance. Policymakers had expected academic achievement to be driven by quantitative inputs (that is, educational spending), but the meticulous research conducted by Coleman and his team demonstrated that it was the qualitative features of schools that were essential to improving academic performance.

The report disappointed many in the Administration, for it emphasized that student outcomes were less a function of government spending and more a matter of what Coleman would come to define as “social capital”: those influences on individual and group actions derived from networks of relationships involving trust, obligations, norms, sanctions, and recognized authorities. Social capital, it should be noted, can be used for good or ill, which leads to a fundamental question: What types of social capital produce the best K–12 academic outcomes?

Educational Sources of Social Capital

In previous generations, Americans drew social capital from various intellectual authorities, most of whom could be found among the primary sources studied in classical schools. Stretching from antiquity to modernity, the great books of Aristotle, Augustine, Cicero, Descartes, Euclid, Homer, Locke, Shakespeare, and dozens of other canonical works served as the intellectual gold standard for America’s cultural currency.

Unfortunately, over the past century, progressive educational leaders—from John Dewey to David Coleman—have systematically eroded the influence of great books, causing a decisive break with the educational standards of the past. Great works of literature, history, mathematics, and philosophy (many written in Latin or Greek), along with training in the fine arts and the pedagogy of the seven liberal arts, have largely been displaced by contemporary, progressive notions of schooling. Against the perennial, classical approach, progressive education claims a scientific basis for its methods, seeking to construct efficient systems for achieving K–12 literacy and numeracy and to prepare the next generation for success in the marketplace (think “career ready”) and participation in democratic institutions (read: political activism). Replacing great books (classical) education with contemporary “social studies” has become a distinguishing feature of the progressive approach.

While job skills and civic participation are surely desirable ends, they are not the primary ends of classical education. In short, a classical education aims to provide a formative, inspiring encounter with the best recorded thoughts in history (hence the Great Books), from which students can develop their own thoughts, abilities, and values, in preparation for their full participation in society—as members of families, neighborhoods, religious organizations, schools, businesses, and other civic and political institutions. To that end, students in classical schools will study fewer subjects—but in greater depth—to explore the fundamental and perennial questions surrounding human nature, human societies, and human happiness.

The progressive approach to schooling consists of a variety of projects, yet its educational ideology can be distilled into four essential features. As educational historian Diane Ravitch explains, the traditional academic curriculum was gradually displaced by four ideological commitments:

- education as a science, with precise measures of outcomes—such as standardized testing;

- education as a child-centered activity—as espoused by the self-esteem movement;

- education as social and vocational training—for instance for “life skills”; and

- education as social reform—such as political activism.3

By contrast, classical schools are oriented toward (1) the sometimes opaque arts of language and thought, with the goal of increasing precision and clarity in thinking and writing; (2) a long-standing tradition of great works, which serve to draw students out of themselves toward greater aspirations; (3) a humane exploration of nature and humanity’s place in the cosmos; and (4) a philosophical approach to politics, which aims to encourage greater civic duty and participation. In all of this, classical schools strive to model excellent thought and practice, such that great ideas are integrated with moral exemplars, where the quality of great books is matched by the caliber of those teaching the books. The expectation, of course, is that students will emulate both models.

Historical Clashes Over Classical Education

Increasingly, classical education in America has become the province of self-selecting families with the financial resources and determination to retain something of the private “college prep” school—such as the Groton School, Episcopal Academy in Philadelphia, or the Phillips Exeter Academy. Such places still provide the opportunity to study Latin, the humanities, math, and the sciences inside ivy-covered buildings at institutions with an academic pedigree. But these elite schools are out of reach for the majority of Americans.

With this cordoning off of the classical approach, progressive ideas have come to dominate K–12 education in America for nearly a century.

Even so, there have been hold-outs. For example, under the influence of President Robert Hutchins and Professor Mortimer Adler at the University of Chicago, great books experienced a resurgence among the general public throughout the 1940s and 1950s. With essays in The Saturday Evening Post, popular books (such as Education for Freedom), and a great books collaboration with the Encyclopedia Britannica, Hutchins and Adler offered a compelling vision for the study of masterful works.

Meanwhile, education professors were perturbed by popular interest in perennial classics, exclaiming (in various ways) that great books are, to borrow the words of John Dewey, a return to “the medieval pre-scientific doctrine of supernatural foundations and outlook in all social and moral subjects.”4 How could Dewey, a renowned philosopher, make such a spurious, exaggerated charge against the classical sources of American ideals?

Jacques Barzun, the provost of Columbia University, pointed to the nation’s loss of intellectual discipline, attributing its decline to the intellectual class.5 Post–World War II America was shaped by a steady “neglect of intellectual discipline…denying the young the benefits of the long collective effort of Intellect which is their birthright.”6 Dewey’s dismissive commentary on the Great Books is but one early example of what Barzun would identify as the intellectuals’ failure to propagate “the Western tradition of explicitness and energy, of inquiry and debate, of public, secular tests and social accountability.”7 Midcentury intellectuals and institutions of higher education were turning away from their “birthright” to alternative visions (or, perhaps, delusions) of the intellect, usurping the pride of place formerly given to great literature, philosophy, and history.

This seemingly internecine squabble had implications for America’s youth. As James Coleman began to observe, a distinct segment of the population, which he described in his 1961 book Adolescent Society, was turning its back on the life of the mind.8 Coleman surveyed 10 Midwestern high schools and discovered a growing trend among teenagers: “[T]he adolescent subcultures in these schools exert a rather strong deterrent to academic achievement.”9 Not surprisingly, as intellectual activity was devalued, athletic prowess and social desirability became the primary measures of status in secondary schools, reinforcing the anti-intellectual and materialistic disposition of modern Americans.

The watershed events of the 1960s proved to further unmoor the American mind. The escalation of Cold War activities, the decolonization of the globe, crucial episodes in the Civil Rights movement, and disturbing losses from the Vietnam War all begged for a coherent explanation from America’s intellectual class. Yet, none was forthcoming except the increasingly shrill claim that “Western hegemony” was responsible for most, if not all, of society’s failures.

Alongside social reformers in the 1970s, progressive educators urged policymakers to promote greater social equity by redesigning public schools: instituting desegregation via bussing, addressing achievement gaps and promoting affirmative action, lessening curricular requirements and increasing electives, eliminating dress codes and easing discipline. But, to what end? Certainly, students had greater freedom to choose their “academic” course of study. But, the end result was predictable: declining academic performance.

A study by the U.S. Department of Education compared high school graduates from 1972 to those in 1980, in which researchers discovered a number of dramatic changes in students’ behavior and academic performance: falling test scores in verbal skills and mathematics, fewer hours spent on homework, and avoidance of academic curricula (students preferring electives).10 Moreover, over the course of the decade, the behavior of the adults (teachers) also shifted, with clear signs of grade inflation. The study uncovered one Pyrrhic victory: Graduates from 1980 rated themselves higher on self-esteem than did their 1972 counterparts. (At least they felt good about themselves!)

In the 1980s, the bad news continued, with a shocking national report in 1983 revealing serious academic deficiencies among American secondary students. A Nation at Risk warned, in language colored by Cold War metaphors, that American education was in serious jeopardy: “[T]he educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.”11 The report called for a much higher level of “shared education…essential to a free, democratic society and to the fostering of a common culture.” The national furor was followed by a spate of books detailing the need to get “back to basics”—including E. D. Hirsch’s argument for the recovery of “cultural literacy” and a curriculum of “core knowledge.”12 These various efforts to recover “intellectual discipline” gave birth to the era of standards and assessment, which continues to the present day.

But, while standards and appropriate assessments are essential to instruction, American K–12 schools have all but divorced standards from content. Moreover, the ubiquitous references to “skills” (such as critical thinking, comprehension, and communication) in most state standards do not incorporate sufficiently specific features of language (such as grammar and logic) that are necessary to employ such skills. Preferring generic language that permits myriad interpretations, such standards are accompanied by tests drawn from the diminished content of contemporary textbooks—which provide excerpts and highlights instead of complete works of literature, history, and philosophy. Such is the “state of the art” in K–12 education in today’s America.

Signs of Hope

Out of this educational malaise, a handful of private, often religious, schools were formed beginning in the 1980s. Parents, teachers, and community leaders who were committed to rediscovering the “lost tools of learning” found common cause.13 The efforts of Kerry Koller (Trinity Schools), Douglas Wilson (Association of Christian Classical Schools), Cheryl Lowe (Memoria Press), Andrew Kern (Circe Institute), and others provided these private schools with classical content and pedagogy, representing a viable alternative to the vacuous intellectual and moral substance of standard K–12 education. This renewal movement inspired thoughtful parents and teachers to pursue a more excellent way—reading Great Books and practicing the liberal arts.

Meanwhile, as the general electorate continued to demand better public schools, educational leaders and policymakers advanced an alternative to the typical district model. The idea for charter schools was designed by a university professor (Ray Budde of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst), embraced by an educational union leader (Al Shanker of the American Federation of Teachers), and eventually inaugurated in Minnesota in 1991.14 In the following decades, charter school laws would pass in 44 states, providing an “educational choice” for public school families.

Arizona was an early adopter, passing its charter law in 1994. Two years later, another group of concerned parents, teachers, and state policymakers joined forces to launch a charter school based on the classical model. Tempe Preparatory Academy looked to the Trinity Schools (founded in 1981) for a curricular framework. As one of the earliest charter schools in Arizona, Tempe Prep, for grades seven to 12, was distinctively classical, offering a one-track, six-year course of study that included languages, mathematics, the sciences, fine arts, and an integrated humanities course called “humane letters”—a seminar-discussion featuring great books of literature, history, and philosophy.

In 2003, with an increasing sense of parental demand for this type of school, a number of board members, teachers, and parents from Tempe Prep opened yet another charter school, Veritas Preparatory Academy, along the same curricular and pedagogical lines. This group, however, had an additional ambition: to form a network of classical charter schools known as Great Hearts America.15 The first organization to scale the classical model through charter schools, Great Hearts has grown in 16 years to serve more than 18,000 students, operating 30 academies in Phoenix, San Antonio, and Dallas–Fort Worth—with aspirations to serve many more families across the country.

Founded to fulfill Mortimer Adler’s claim that the “best education for the best is the best education for all,” Great Hearts has proven that claim among students from all backgrounds, exceeding private school performance and generating elite college admissions. More important, the organization promotes the formation of virtuous young men and women, within communities of families and teachers who are committed to the development of minds and hearts. With 15,000 students on its waitlist, Great Hearts has demonstrated the need for this kind of social capital.

Beginning in 2012, another provider began to support new classical charter schools: Hillsdale College. Under the college’s banner (and with generous funding from the Barney Family Foundation), the Barney Charter School Initiative has provided material support and training for the launch of an average of three schools a year since 2012—for a total of 25 schools as of fall 2019.

Today, more than 210 classical charter schools can be found across the country in 30 states, with particular concentrations in Arizona, Colorado, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Texas. Most of them operate as single charters (apart from a management organization), yet the majority characterize themselves by distinctively demanding academic subjects (such as Latin, humane letters, and Euclidian geometry), and focusing on students’ moral development.

While the overall charter sector includes nearly 7,000 schools in 44 states and the District of Columbia serving more than 3 million students, classical charters serve approximately 3 percent of those students (100,000 students). In part, that is a function of their size. They are smaller schools, averaging between 400 students and 600 students each, and they appear to be relatively local phenomena. Just as with the private classical schools that emerged in the 1980s, classical charter schools are being driven by families, teachers, and policymakers who value schools founded on the academic and moral qualities that are essential for sustaining communities. They are creating the cultural endowment of a rich, intellectual tradition alongside the values and sentiments that typify good neighbors and citizens.

Unexpected Results

Under the banner of Johnson’s Great Society, the federal government provided a surprising gift to those concerned with the expansive role of the administrative state: It funded James Coleman’s work. Following the empirical evidence to truly insightful conclusions, Coleman pointed to the loss of social capital at the heart of American society—particularly in K–12 public education. Over the course of his research career, Coleman produced striking and sophisticated support for his overall view: He had described a developing adolescent subculture increasingly resistant to academic pursuits; he had shown that monetary inputs alone are insufficient for reversing academic decline; he had demonstrated the unintended negative consequences of school bussing policies; and he had promoted the academic and cultural achievements of private, religious schools as models of excellence. By the end of his career, Coleman concluded that a coherent curriculum delivered within a community of people who have values in common provides the essential social capital for individual academic achievement.

Today there is a recovery of that cultural endowment that includes the integrated study of the essential subjects, as delivered within a liberal arts pedagogy. Remarkably, families are attracted to these schools, for they see them as institutions of cultural renewal, recovering traditional content (which is increasingly uncommon), and revitalizing school cultures—where students’ intellectual and moral development are integrated. Perhaps those parents are seeing what James Coleman observed in his quest to increase genuine educational equity: Social and cultural capital are the foremost features of anyone’s education.

REFERENCES

- James S. Coleman et al., Equality of Educational Opportunity (Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics, 1966), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED012275.pdf (accessed July 24, 2019).

- Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson, “Coleman Report Set the Standard for the Study of Public Education,” Johns Hopkins Magazine (Winter 2016), https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2016/winter/coleman-report-public-education/ (accessed July 24, 2019).

- Diane Ravitch, Left Back: A Century of Failed School Reforms (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

- John Dewey et al., The Authoritarian Attempt to Capture Education: Papers from the Second Conference on the Scientific Spirit and Democratic Faith (New York: Kings Crown Press, 1945).

- Ibid.

- Jacques Barzun, The House of Intellect (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959).

- Ibid.

- James S. Coleman, The Adolescent Society: The Social Life of the Teenager and Its Impact on Education (New York: Free Press, 1961).

- Ibid.

- William B. Fetters, George H. Brown, and Jeffrey A. Owings, High School Seniors: A Comparative Study of the Classes of 1972 and 1980 (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 1984).

- National Commission on Excellence in Education, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983).

- E.D. Hirsch Jr., Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987).

- Dorothy L. Sayers, The Lost Tools of Learning (Louisville, KY: GLH Publishing, 2017); originally delivered in a 1947 speech at Oxford University.

- Jon Schroeder, Ripples of Innovation: Charter Schooling in Minnesota, the Nation’s First Charter School State (Washington, DC: Progressive Policy Institute, 2004).

- This author is chief academic officer of Great Hearts America.