Fusionists insist that the liberal democratic emphasis upon the dignity of the human person is unintelligible apart from biblical assumptions. Equality of human persons under law, one of the most foundational of liberal political principles, is grounded in a theological vision of things. Both the rule of law and the notion of limited government are biblical in inspiration.

The issue of the relationship between liberal democracy and the Catholic Church has long been a vexed one. If one consults Catholic leaders in the 19th century, very much including the popes who dominated that century, namely, Pius IX and Leo XIII, one would find fairly vigorous condemnations of capitalism and the liberal order. Moreover, if one surveyed the writings of leading figures within the American polity of the same century, one would discover sharply worded critiques of Catholicism as a system alien to the American way of life. For a particularly good example, look at Ulysses S. Grant’s appraisal in 1875 that Catholicism could prove more divisive in America than the Confederacy itself had been. And if one harbors any doubts whether this attitude survived well into the 20th century, one need look no further than the ruminations of Woodrow Wilson and the warnings of a slew of cultural leaders at the prospect of a Catholic president in 1960.

A Rapprochement

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, a number of Catholic ecclesiastics, including James Gibbons, the Archbishop of Baltimore, and John Ireland, the Archbishop of St. Paul-Minneapolis, commenced to advocate for a rapprochement between Catholicism and American democracy. Subsequently, toward the middle of the last century, Catholic academics such as John Courtney Murray and John Ryan began to articulate in a more rationally disciplined manner the points of contact between classical Catholic political philosophy and the principles of liberalism.

The ruminations of both ecclesiastics and academics often centered around the importance of toleration and religious liberty.

The ruminations of both ecclesiastics and academics often centered around the importance of toleration and religious liberty. And, indeed, the Vatican II document Dignitatis Humanae, largely penned by Courtney Murray, made the American approach to the rapport between objective religious truth and freedom of conscience a part of the official teaching of the Catholic Church.

In the years following Vatican II, a plethora of influential players within the Catholic academy in the United States emerged to continue and deepen this line of thought. One thinks of George Weigel, Michael Novak, Robert George, Robert Sirico, and perhaps especially of Richard John Neuhaus. Their influence upon St. John Paul II became unmistakably clear in the great pope’s 1991 encyclical letter Centesimus Annus, simultaneously a celebration of Leo XIII’s groundbreaking Rerum Novarum from 1891 and a thoughtful consideration of the events of 1989. In the course of that letter, John Paul enthusiastically endorsed the market economy and the form of liberal democracy that existed generally in the West.

Fusionism

Looking more deeply into the arguments presented by this school of thought—referred to today as “fusionist,” since it appreciates the tight connection between Catholicism and political modernity—there are a number of key themes.

Individual Dignity. First, the fusionists insist that the liberal democratic emphasis upon the dignity of the individual is unintelligible apart from biblical assumptions. Thomas Jefferson implied as much when he said, in the prologue to the Declaration of Independence, that all people are “endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.” If rights are granted by the state, they can be withdrawn when it is convenient for the state to do so. If they are a function of a cultural consensus, they can disappear when that consensus evanesces. History, of course, provides numerous examples of precisely these moves.

Equality. Furthermore, equality, one of the most foundational of liberal political principles, is grounded in a theological vision of things. As the ancient political theorists saw with such clarity, human beings are, in almost every regard, radically unequal—in size, strength, beauty, moral virtue, and courage, etc. In point of fact, the political systems proposed by both Plato and Aristotle are predicated upon the assumption of irreducible inequality among the members of the polis. For Plato, everyone in the city falls into one of three altogether distinct social classes, and for Aristotle, only a small contingent of propertied, intelligent males are permitted to partake of authentically public life.

Despite enormous inequalities in practically every respect, humans are indeed all equally children of God, created by choice of his will and destined to share eternal life with Him.

Once again, Jefferson gives away the game when he claims as self-evident the assertion “all men are created equal.” Despite enormous inequalities in practically every respect, we are indeed all equally children of God, created by choice of his will and destined to share eternal life with Him. Take God out of the picture, and it becomes extremely difficult to defend this crucial principle of a democratic polity.

Biblical Inspiration. Finally, both the rule of law and the notion of limited government are biblical in inspiration. Time and again, the prophets remind the Israelite kings of their obligation to follow Torah and that those potentates stand, whether they like it or not, under the judgment of God. This means that the law has primacy over the whims and private desires of anyone, including and especially kings. More to it, the sovereignty of God implies that the scope and power of any earthly rule are strictly limited, hemmed in by the demands of the moral law. We might refer in this context to the magnificent criticism of the corruption of kings found in the speech given by the prophet Samuel. The fusionists have long argued persuasively that the myriad restrictions placed on civic leaders within a democratic polity, as well as the system of checks and balances, are predicated finally on these biblical assumptions.

The sovereignty of God implies that the scope and power of any earthly rule are strictly limited, hemmed in by the demands of the moral law.

Hobbes and Locke

Now all these observations lead me back to the beginning of my presentation. If all of this is true—and I indeed think it is—why did so many reflective people, and not just bigots, on either side of the Catholic/American divide seem to feel that the two systems of thought were incompatible? To provide a fully adequate response to that question would take me far beyond the confines of this paper, but permit me to explore at least a few angles.

Hobbes. Anti-liberal Catholic theorists would have drawn attention to the roots of liberalism in the thought of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and would have remarked how those thinkers represented a radical rupture from the classically Catholic understanding of both the political and moral orders. In this regard, Hobbes is particularly instructive. Consciously breaking with the long tradition of political philosophy that preceded him, Hobbes endeavored to articulate a science of politics, like in form and purpose to the physical sciences that were beginning to emerge in his time. This amounted to a setting aside of final causality and questions of moral aims and an embrace of efficient causality in the political order.

Accordingly, Hobbes set out to explore what actually motivates human beings to act as they do, and his reductionistic conclusion was that the efficient causes of our behavior are, at bottom, the emotions accompanying the desire to preserve life and to avoid violent death. This quotation from chapter 11 of Leviathan signals the sea-change that Hobbes represents: “The Felicity of this life, consisteth not in the repose of a mind satisfied. For there is no such Finis Ultimus (utmost ayme,) nor Summum Bonum (greatest good) as is spoken of in the Books of the old Morall Philosophers [sic].”REF The complete relativizing of truth and goodness in the Hobbesian program becomes clear, furthermore, in this passage from the sixth chapter of Leviathan: “Whatsoever is the object of any mans Appetite or Desire; that is it, which he for his part calleth Good: And the object of his Hate and Aversion, evill [sic].”REF

Whereas classical politics was predicated upon a keen sense of objective moral values and indeed a highest good to which all people aspire by nature, Hobbesian politics was predicated upon the preservation of biological life. Now any collectivity of individuals, all motivated by a selfish desire to live and to avoid violent death, will necessarily come into conflict with one another and the result will be, in Hobbes’s famous phrase, a life that is “solitary, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Whereas classical politics was predicated upon a keen sense of objective moral values, Hobbesian politics was predicated upon the preservation of biological life.

It is only to avoid this intolerable situation that human beings resolve to enter a social contract by which they surrender their rights and prerogatives to the Leviathan state. The practically unlimited authority granted to the sovereign is, paradoxically, in the self-interest of each party to the contract. Once again, Hobbes would insist that the sovereign remains utterly indifferent to matters of moral excellence or spiritual attainment; rather, his purpose is to protect warring individuals from one another. And this touches on a deeper matter, namely, Hobbes’s unambiguous assumption that, pace practically the entire tradition of political philosophy that came before him, we are not by nature political or social. We are so only artificially and by means of a contractual contrivance. Relatedly, we are not naturally good or ordered to friendship—just the contrary. The entire Hobbesian program rests upon the conviction that our natural state is one of utter self-interest and hostility to our neighbors. In his pithy formula: the state of nature is the state of war.

Locke. Now Hobbes’s program was, in essentials, adopted by John Locke, though Locke softened it in certain regards. For instance, he opined that a kind of natural moral law obtained even in the pre-political state of nature, and he held that one exited that state by means of two contracts, not one as in Hobbes, thus allowing for the possibility of rebelling against a corrupt state without reverting, ipso facto, into the state of war. But the amoral, non-teleological conception of political life remained in place.

Thus, for Locke, rights are but a function of our desire to preserve life and avoid violent death. In his language, we have a right to those things that we cannot not desire: life itself, and its necessary concomitants, liberty and property. Any sense of a transcendent good to which human life is properly ordered or of a common good that goes beyond the mere physical well-being of the members of the political society is, in the Hobbesian manner, missing. The government, which secures these rights, remains, if I might put it this way, protective rather than directive. This citation from Locke’s letter on toleration is apposite here: “The commonwealth seems to me to be a society of men constituted only for the procuring, preserving, and advancing their own civil interests…. Civil interests I call life, liberty, health, and indolency [sic] of body; and the possession of outward things, such as money, lands, houses, furniture, and the like.”REF

The Lockean suspension of the metaphysical good becomes even clearer when one ventures outside of Locke’s explicitly political writing and turns to his epistemological masterpiece, An Essay on Human Understanding.REF In this text, Locke lays out a revolutionary idea of will as primarily an active power of self-determination. Whereas on the traditional reading, a good outside of the will prompts that faculty to respond. On Locke’s interpretation, the will has ontological primacy and remains undetermined by anything outside itself. Here is his account: “For that which determines the general power of directing, to this or that particular direction, is nothing but the agent itself exercising the power it has that particular way.”REF

In a radical departure from the standard interpretation, Locke holds that the direct object of the will is not a thing but an action, namely its own.

In a radical departure from the standard interpretation, Locke holds that the direct object of the will is not a thing but an action, namely its own. Rather than appreciating the will as extending itself into reality, Locke effectively shrinks its area of concern. Here is Locke’s own extremely clear and illuminating formulation, “the will or power of volition is conversant about nothing but our own actions; terminates there; and reaches no further.”REF So concerned is he to maintain the control that the will has over itself, Locke argues that the self “not only begins its act of will from itself alone, but that movement likewise ends exclusively in the self as the will’s proper object.”REF Whatever connection eventually obtains with the world outside the dynamics of the will remains secondary and extrinsic, subordinate to the sovereignty and sufficiency of the choosing self.

The Limitations Hobbesian–Lockean Thought

This treatment of the thought of Locke permits me to quote the man for whom this lecture series is named. Throughout his career, Russell Kirk remained disquieted by the manner in which Locke departed from the classical political tradition. Instead of being created in the image of God, man is, on Locke’s interpretation, simply homo economicus, and his purpose is not to do the will of God or to pursue the common good, but rather to protect his property rights. “There is,” Kirk concluded, “no warmth in Locke, and no sense of consecration,” and “utility, not love, is the motive of Locke’s individualism.”REF

It is difficult not to see that the prologue to Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration is a distinctively modern text.

What was concerning to many Catholic theorists of the 19th century was precisely this Hobbesian–Lockean reductionism regarding political life, which they saw on display in the most important of the founding documents of our country. Without gainsaying for a moment the observations made above regarding its biblical overtones, it is difficult not to see that the prologue to Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration is a distinctively modern text.

First, the conventional/artificial nature of the political enterprise is defended, as well as a fundamentally Hobbesian–Lockean view of the rights that government is invented to defend. To be sure, Jefferson has adjusted the Lockean triplet of life, liberty, and property to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but that adjustment only confirms the manner in which Jefferson departs from classical political philosophy.

For the great Western philosophical tradition, the determination of what constitutes objective happiness was a major preoccupation. Think of Aristotle’s treatment of virtue in relation to eudamonia in the Nichomachan Ethics, Plato’s subtle phenomenology of the good in a variety of dialogues, and Thomas Aquinas’s exhaustive analysis of beatitudo at the commencement of the Prima Secundae. And in all three of those thinkers, the objective good was construed as the determining factor in the establishment of a just social order. But in Jefferson, all of this is left to the self-determination of the individual subject, the pursuit of happiness, rather than happiness itself, taking pride of place.

These worries of 19th- and 20th-century figures are taken up by several Catholic scholars today who question the philosophical underpinnings of the American founding. One thinks of, among others, Adrian Vermeule, Patrick Deneen, D. C. Schindler, and Edmund Waldstein. All these philosophers maintain that the distinctively modern or post-Christian metaphysics informing the political speculations of the Founders fatally compromise the practical arrangements that they put in place. So, the question naturally arises: Who has this at least relatively right, the fusionists or the neo-integralists? Is American-style liberalism compatible with or repugnant to Catholic Christianity? An adequate answer to that vexed question would go far beyond the confines of this brief presentation, but at the risk of sounding facile, I would venture to respond “both.”

My position is that the American polity is fundamentally modern in form and inspiration but that it remains conditioned by certain deeply held religious assumptions. It is a Hobbesian–Lockean system but with overtones of the Christian worldview that still haunted the minds of the Founders, and—perhaps more importantly—shaped the souls of the first American citizens.

The American polity is fundamentally modern in form and inspiration, but it remains conditioned by certain deeply held religious assumptions.

Tocqueville’s Observations

It is almost a cliché to point it out, but no one managed to pick his way through this intellectual thicket more perceptively or creatively than the 19th-century French diplomat and political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville. After an extensive tour of the Andrew Jackson–era United States in the mid-1830s, Tocqueville shared what he had discovered about the peculiarly American manner of reconciling liberalism with an ardent religiosity. His conclusion, in a word, is that the latter effectively makes possible the former, or better, provides it with an animating purpose. A handful of citations sum up his argument: “The Americans combine the notions of religion and liberty so intimately in their minds, that it is impossible to make them conceive of one without the other.”REF And, “It must never be forgotten that religion gave birth to Anglo-American society. In the United States religion is therefore commingled with all the habits of the nation and all the feelings of patriotism; whence it derives a peculiar force.”REF And, “[s]o religion, which among the Americans never directly takes part in the government of society, must be considered as the first of their political institutions; for if it does not give them the taste for liberty, it singularly facilitates their use of it.”REF

On Tocqueville’s view, the vibrant religiosity of America served as a corrective and a complement to the Hobbesian nature of the liberal government, rounding its pointed edges.

This last quotation is perhaps the most illuminating, for it articulates the idea of ordered liberty, or freedom, not as an end in itself, but as directed to a moral good. Tocqueville saw that the proposal of the moral good is not the business of a liberal government, which retains its typically modern agnosticism in that regard, but is offered to the society through the ministrations of the churches and religious institutions that pervade the commonwealth. We might say that, on his view, the vibrant religiosity of America served as a corrective and a complement to the Hobbesian nature of the liberal government, rounding its pointed edges.

Though there are many concrete examples of this dynamic that could be cited, suffice it to say that the two greatest social transformations in American history, namely, the end of slavery and the end of racial segregation, were both prompted by religious people, drawing their moral inspiration from the texts of the Bible. The suggestion of the ethical good in both cases did not come, as it were, from above the secular authority, but from below, from a religiously saturated culture.

The end of slavery and the end of racial segregation were both prompted by religious people, drawing their moral inspiration from the texts of the Bible.

The Collapse of the Tocquevillian Equilibrium

All of these reflections bring us to what is perhaps the most significant cultural phenomenon of modern time: what we would characterize as the collapse of the Tocquevillian equilibrium. The last roughly 60 years have witnessed a disturbing unravelling of the religious texture of society, unprecedented in American history, and indeed, in all of history. As Charles Taylor has indicated, it would have been unthinkable for someone in, say, 1500 to believe that happiness could be had apart from a reference to God, but now non-belief in God and the acceptance of a completely this-worldly frame of reference for human flourishing are widespread.

The mainstream Protestant churches in the United States are in freefall, and Catholicism is not far behind, its numbers relatively strong only due to immigration. In 1970, roughly 3 percent of Americans would have described themselves as having no religious affiliation, but today that figure has risen to 25 percent, and it rises still higher to 40 percent among those under 30. Though these trends were emerging 30 years ago, commentators at that time tended to reassure us that, though fewer and fewer people were attending church services, the basics of religion—belief in God, the afterlife, the existence of the soul, and basic moral principles, etc.—remained in place.

One of the most conspicuous consequences of the collapse of institutional religion is what Joseph Ratzinger called “the dictatorship of relativism.”

The sociological work of Father Andrew Greeley from the 1970s and 1980s is an extremely instructive example. But in accord with the Will Herberg “cut-flowers principle,” all of these convictions, once deracinated from concrete religious practice and institutional affiliation, endured for a time but then commenced rapidly to dry up. And as Tocqueville would have foreseen, this waning has had enormous political and cultural implications, permitting the more severe Hobbesian structure of polity to assert itself.

The Dictatorship of Relativism

One of the most conspicuous consequences of the collapse of institutional religion is what Joseph Ratzinger called “the dictatorship of relativism,” or the conviction that there is no objective ground for morality—and certainly no summum bonum which would serve to regulate human thought and activity. Absent this normativity, the freedom of the individual comes to generate value. Instead of imitating and appropriating for oneself the objective goods of the natural and moral orders, the sovereign self creates a personal good and cultivates a personal truth. In the words of Carl Trueman, mimesis has given way to poiesis: imitation to creation.

One of the clearest artistic expressions of this viewpoint was the film that won the Academy Award for best picture a few years ago: The Shape of Water. The plot of the film was (believe it or not) a young woman who falls in love and then has sexual relations with a creature half-human and half-fish. The villain of the story, of course, was a believing Christian, presented as a boorish hypocrite. But the title gave away the game: The only shape there is is the shape of water, which has no form except the one that we choose to give it.

Though this understanding held sway in Hobbes, and in a more mitigated form in Locke, it was largely covered over by the widespread and deeply held religious convictions of most Americans prior to 1960. And though this is not immediately obvious to most, the subjectivization of value conduces automatically to the war of all against all, for there is no common point of reference, no transcendent set of norms to which all people in common can submit themselves, but only autonomous individuals, atoms with no natural affinity to one another.

The subjectivization of value conduces automatically to the war of all against all.

If you find yourself doubting whether this state of war obtains, go any time of the day or night on Twitter or practically any social media site that allows for comments. Arguments about moral and intellectual matters have largely disappeared from those massively popular venues because authentic argument is based upon some sense of shared assumptions and values. All that is left is shouting insults at one another from opposing trenches.

Numerous studies have indicated that young people who frequent social media sites are beleaguered, depressed, and suffer from something akin to post-traumatic stress disorder. In further support of my thesis that in the absence of religion, the Hobbesianism of the American experiment has re-asserted itself, I would draw your attention to one of the principal preoccupations of young people today: safe spaces, guaranteed by municipal, university, or government authority. What seems to preoccupy many today is, once again, the protective rather than directive purpose of authority. It is not at all surprising, moreover, that many studies have indicated how young people in our country increasingly are suspicious of freedom of speech and are increasingly open to more powerful government regulation—two basic tenets of the Hobbesian program.

What seems to preoccupy many today is the protective rather than directive purpose of authority.

Reclaiming the Objectively Valuable

So, what is the solution? It is facile enough to say that we should go back to the cultural consensus that existed prior to 1960, and which was instantiated through a plethora of mediating institutions. It would, at the very least, take time to build back that structure, if such were even possible. I might suggest as a first step the recovery of the sense, especially in young people, of the objectively valuable as opposed to the merely subjectively satisfying.

In using this language, I am borrowing the terminology of Dietrich von Hildebrand, one of the most significant Catholic philosophers of the last century. As an example of the merely subjectively satisfying, Hildebrand frequently proposed the receiving of an unjustified compliment. Though kind words typically produce a rush of good feeling in the one who receives them, there is, in the case of such a compliment, nothing of substance behind them. They merely flatter the ego and leave it unchanged, unchallenged. Those empty words simply find their place within the psychological structure of the ego and do no significant spiritual work.

But the objectively valuable confronts the one who perceives it and changes him, rearranging his psyche. Dante’s Commedia, or Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, or Chartres Cathedral, or the moral heroism of Maximilian Kolbe are not merely subjectively satisfying. Rather, the sheer density of their objective value arrests us, claims us, and sends us on mission as evangelists of their truth and beauty.

Objective values, in the epistemic, moral, and aesthetic orders, arrange themselves naturally in hierarchies.

In the presence of such values, we are, like the great Israelite prophets, placed in the passive voice: We do not so much speak our own truth, but we have heard the word of the Lord. And the connection to God that I’m making here is not incidental, for objective values, in the epistemic, moral, and aesthetic orders, arrange themselves naturally in hierarchies, which means, as Thomas Aquinas saw, that they are named and understood in relation to that which is of highest possible value: the supreme truth, goodness, and beauty. When St. Paul introduces himself to the Romans in his famous epistle, he characterizes himself as “called and sent to be an apostle.” A higher power has claimed him and commissioned him. In a word, the objectively valuable gives the lie to the culture of self-assertion and self-affirmation that so dominates today.

Therefore, if we want to restore the Tocquevillian equilibrium, which gives a liberal democracy its moral and spiritual ballast, let us resist the “Shape of Water” mentality and let us, with confidence and joy, introduce young people to the infinitely more interesting world of objective value.

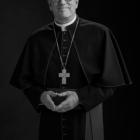

The Most Reverend Robert E. Barron is Bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester and Founder of Word on Fire Catholic Ministries.