Professor Paul Seaton observes in his book Public Philosophy and Patriotism that the Declaration is an American epic poem that speaks to the depths of our political soul:

The Declaration makes clear that even revolutionary action can be warranted. But it also lays down strict criteria for such action. It thus cautions boldness to tether itself to principled, prudential reason, while challenging reason to entertain thoughts of both the worst and the boldest. Possible despotism is perhaps the greatest challenge for political reason. The Declaration wants us to get it right.[33]

A document of such magnitude and range contains immense potential to shape the public conversation in decisive ways, and the Declaration has performed that feat in American history. However, a word about slavery is in order.

Many note the Declaration was silent about slavery, a practice buttressed by public law in most of the colonies at the time the Declaration was approved. The Founders proclaimed liberty and the equality of persons, some contend, but did not confront this practice, thereby permanently marring the Declaration. But did the Second Continental Congress possess the power to overturn slavery? What were its powers to intervene in the legal and economic affairs of each state? None. To have exercised power not legally held would have been a usurpation of authority, making their efforts on behalf of independence fruitless. The immediate objective was the independence of legally unconnected states which had come together for a common political purpose.

To have included aspirational language calling for an end to slavery would have been ill-suited to a document whose objective was to make the case for separation from Great Britain. Jefferson’s reference to the slave trade, later stripped from the document, merely recited that the King had been responsible for forcing this practice on the colonies. However, as Professor Gordon Wood has observed, in the aftermath of the Revolution, the “appeal to liberty but with its idea of citizenship of equal individuals…made slavery in 1776 suddenly seem anomalous to large numbers of Americans.” Moreover, “[b]y 1804 all the Northern states had legally ended slavery, and by 1830 there were fewer than 3,000 black slaves remaining out of a Northern black population of over 125,000.”34 Ending slavery and providing constitutional rights to freed slaves and their descendants was a complicated process, marked by moral failings and public wrongs.

The knowledge that we possess about slavery and race as it has coursed through the history of this republic was not possessed by the Founders. They, like us, did not know the future. Their view was slavery was on a course for “ultimate extinction,” in Lincoln’s words.35 They were wrong on that front for economic and political reasons. We might approach slavery and the study of history, more generally, with prudence and humility. None of us knows the future, but we do have moral principles, virtues, and the good habits and practices they should form. These elements of intellect and heart allow us to shape the always unknowable and unwieldy future in a manner that accords with the dignity of the human person. We can confidently proclaim that the principles in the Declaration and the self-governing habits these principles formed enabled this country to overcome slavery.

Abraham Lincoln forever sanctified in our constitutional discourse the principles of the Declaration in his debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858 over the legal status of slavery and his prosecution of the Civil War. Lincoln’s fundamental contribution was to ensure the equality of the human person would become the guidepost of the American polity. Lincoln’s words and statecraft connect the Declaration to justice by appealing to it as unshakeable truth and lifting our country above its failings. Slavery was finished by the end of the Civil War, and the Declaration was the form and spirit of that monumental task.

Some years later, President Calvin Coolidge built on Lincoln’s foundation in his address honoring the 150th anniversary of the Declaration by underscoring that its words on the equality of human persons were the final word. The country was built on unchanging moral principles. “Amid all the clash of conflicting interests,” Americans can stand on the bedrock of the Declaration and the Constitution. As Coolidge explained:

About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful. It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning cannot be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions.[36]

Coolidge warned against progressive notions that truth is evolutionary and that the present generation’s ideas are superior to those of each generation that precedes it, including the Founding generation. Dispensing with the Declaration of Independence would be a degradation, not an advancement.

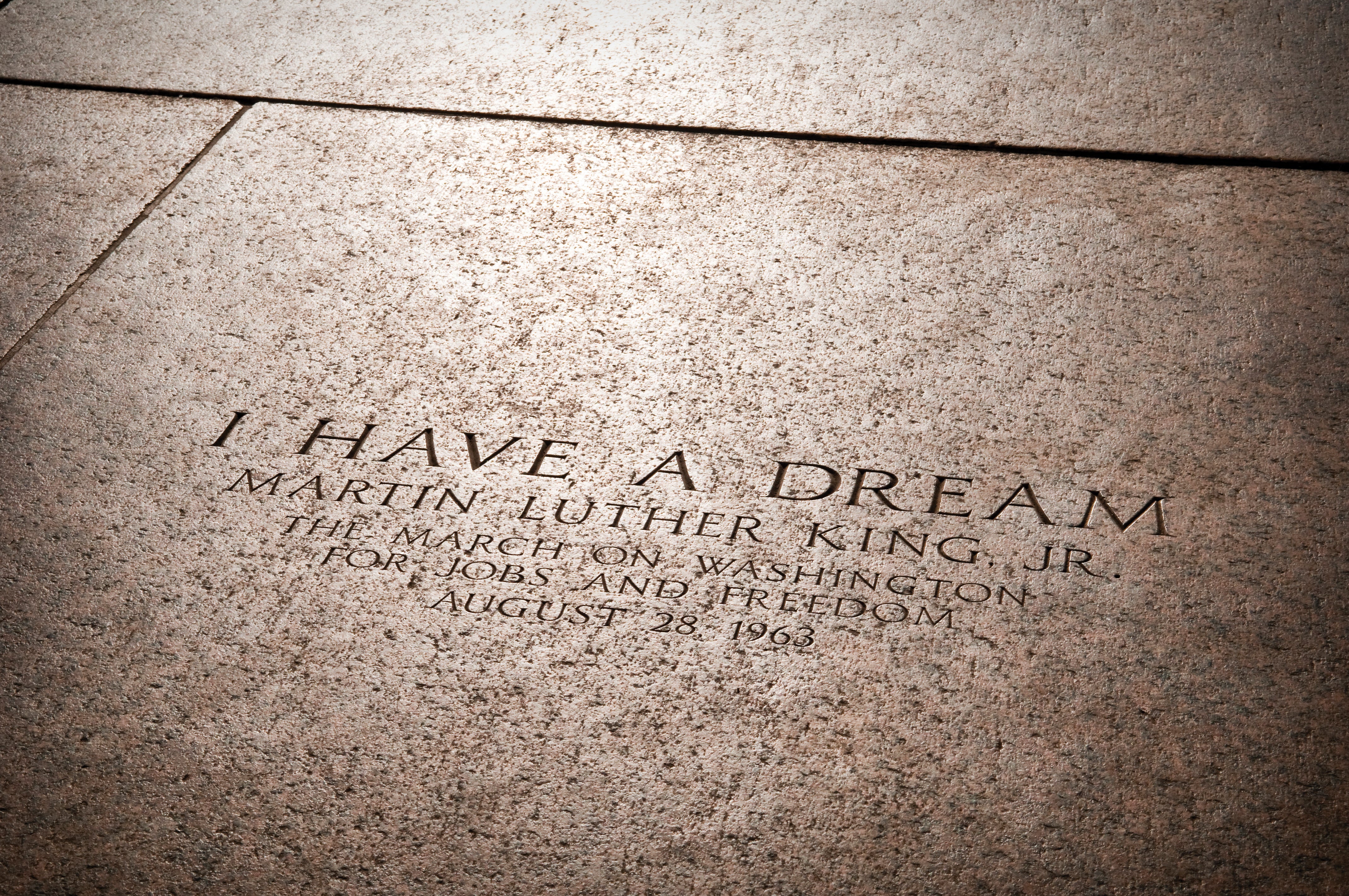

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. King argued that 1963 was “five score years” after Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation establishing that “all men are created equal.” This work, however, is not completed; the promise of the Declaration is yet unfulfilled. He intoned:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”[37]

The American story did not end at the Founding, King reminded Americans dramatically and compellingly. Here are the words of the Declaration, King said, that demonstrate who we are as a people, and their meaning needed to unfold further in the middle of the 20th century.

King’s words are a permanent rebuke to The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, originally a journalistic endeavor by The New York Times, that aims to replace 1776 with 1619, the date the first slaves were allegedly brought to America. The 1619 Project argues that the Founders fought the Revolution to protect slavery. Leading historians have unequivocally rejected their assertion.38 America’s Declaration and Constitution do not amount to a slave-owning republic, as the 1619 Project erroneously states. Those looking for such a republic need only read the Confederate States of America Constitution of 1865, in which the supposed right to own human beings was explicitly enumerated.39

The overall aim of this postmodern history project is to provide a new story of America’s Founding. According to The 1619 Project and adherents of Critical Race Theory, America is irrevocably and irredeemably racist; slavery is our political foundation and our continuing legacy. The only solution, they contend, is to cancel American history and constitutionalism and to replace them with a socialist racialism that will make everyone equal in outcome along racial lines. Such spurious claims must be repeatedly refuted with real history and ideas.

ENDNOTES:

33. Paul Seaton, Public Philosophy and Patriotism: Essays on the Declaration and Us (South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press, 2024), p. 49.

34. Gordon S. Wood, The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States (New York: Penguin Press, 2011), p. 206.

35. Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided’’: Speech, Springfield, Illinois, June 16, 1858.

36. Calvin Coolidge, “The Inspiration of the Declaration,” speech delivered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, July 5, 1926, https://coolidgefoundation.org/resources/inspiration-of-the-declaration-of-independence/ (accessed October 6, 2024).

37. Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream,” speech delivered in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963, https:// (accessed October 6, 2024).

38. A detailed working bibliography of the scholarly criticisms of the 1619 Project has been compiled by economic historian Phillip W. Magness. See Phillip W. Magness, “The 1619 Project Debate: A Bibliography,” American Institute for Economic Research, January 3, 2020, https://www.aier.org/article/the-1619-project-debate-a-bibliography/ (accessed October 4, 2024).

39. The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story (One World , 2021), created by Nikole Hannah-Jones.