Social Security takes a whopping 12.4 percent of American workers’ paychecks, but a new backgrounder by The Heritage Foundation shows that workers are getting a bad deal from the program.

Despite its popularity, Social Security typically provides very low—and in many cases, negative—rates of return.

Although the program provided high returns and windfall benefits to its earliest recipients, Social Security is no longer a good deal for workers.

The Heritage Foundation analysis shows that younger workers—even low-wage ones—would receive at least three times greater rates of return from private savings than Social Security will provide.

To assess Social Security’s so-called “rate of return,” Heritage’s analysis compares what workers would receive if their payroll taxes were invested in personal accounts compared with what Social Security will provide under two scenarios: 1) current law, with roughly 20 percent benefit cuts beginning around 2034; and 2) a scenario whereby payroll taxes rise immediately to a level necessary to pay the program’s prescribed benefits.

While virtually all workers—across income levels, both genders, and generations—would be far better off with personal savings than Social Security, younger workers get the worst deal from the government program.

The average young male worker is virtually guaranteed a negative rate of return from Social Security. Take these hypothetical examples:

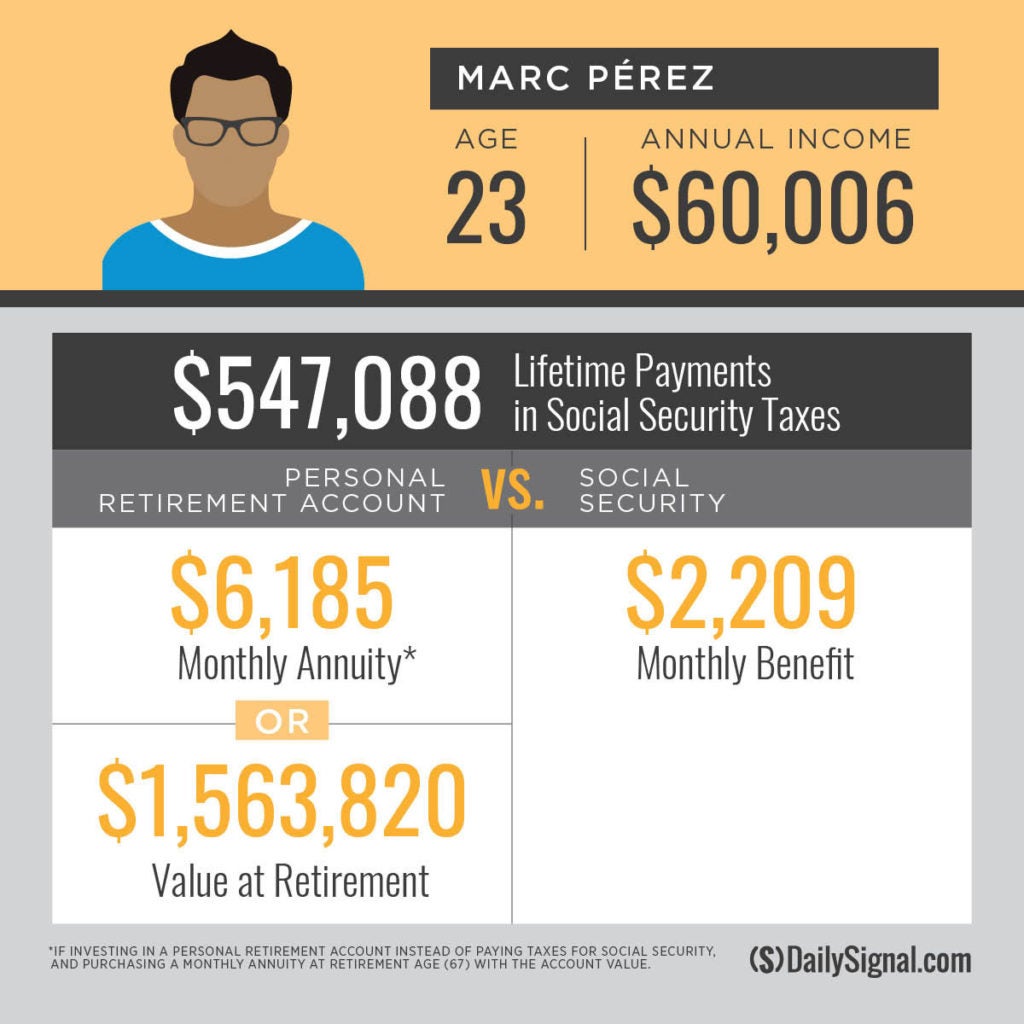

Marc Perez is 23 years old and earns an average income of $60,006 per year. He will pay $547,088 in Social Security taxes (excluding disability insurance taxes) throughout his lifetime. In return, he will receive a monthly benefit of $2,209 in retirement.

If he instead invested that same amount—$547,088—in a conservative mix of stocks and bonds, he would accumulate more than $1.5 million in a retirement account and could use that to purchase a lifetime annuity that would pay him $6,185 per month, or nearly three times what Social Security will provide.

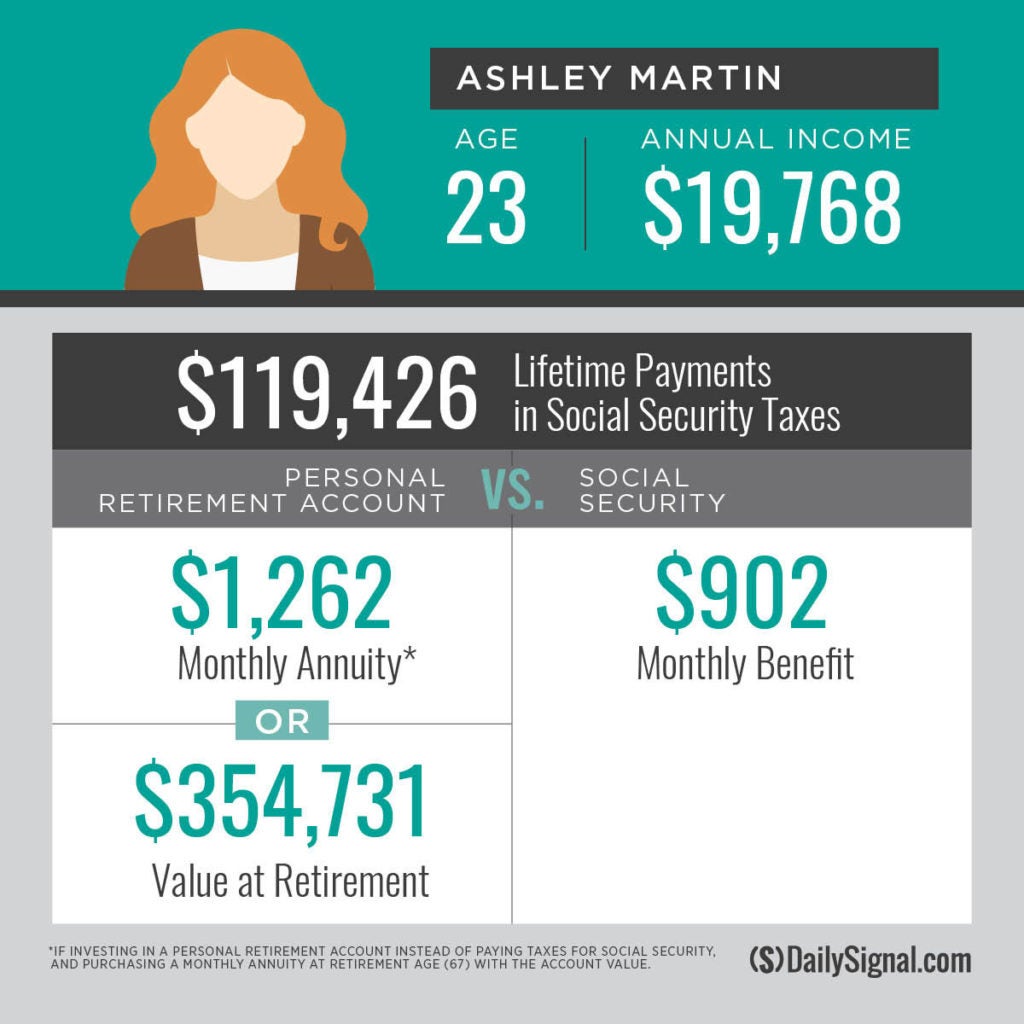

Even lower-income earners, like Ashley Martin, who generally receives higher returns from Social Security would be better off saving and investing in their own personal retirement accounts.

Martin is also 23 and makes $19,768 per year. She will pay an estimated $119,426 in Social Security taxes toward a program that will provide her with a $902 monthly benefit in retirement.

If she instead invested that same amount—$119,426—in her own retirement account, she would accumulate $354,731 in savings. That would be enough to purchase an annuity that would provide her with $1,262 per month, or 40 percent more than Social Security can provide.

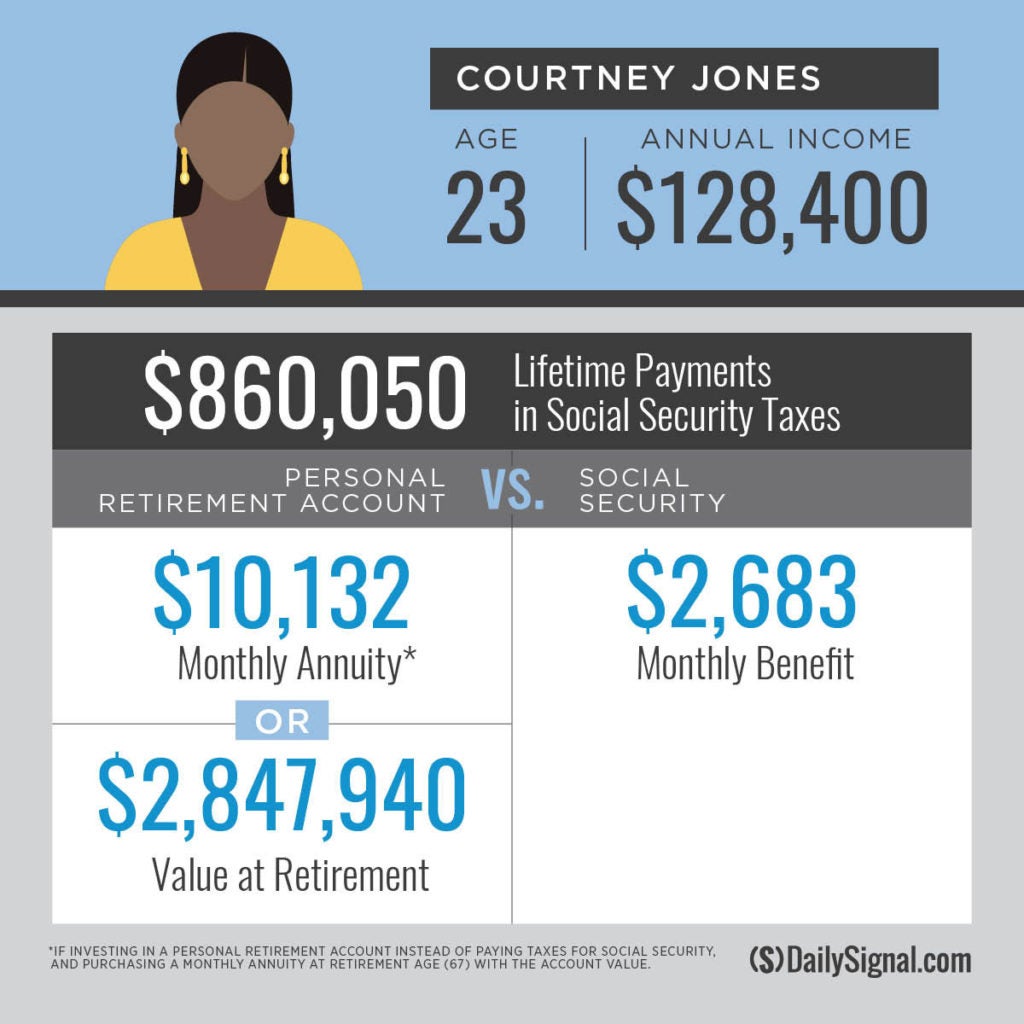

Given the preceding examples, it will come as no surprise that high-income earners like Courtney Jones get the worst deal from Social Security.

Jones is also 23 and makes $128,400 per year (Social Security’s taxable maximum). She will pay $860,050 in Social Security taxes throughout her lifetime and can expect to receive a monthly benefit of $2,683 from the government program.

However, if she invested that $860,050 in her own retirement account, she would accumulate more than $2.8 million in retirement savings—an amount that could provide her with a monthly annuity of $10,132, or almost four times what Social Security can provide.

If workers did not use their personal savings to purchase annuities, but instead drew down on them as needed in retirement, they would be able to leave sizable bequests to their heirs.

In contrast, workers who die before reaching Social Security’s retirement age or shortly thereafter often receive little to nothing in return for their hundreds of thousands of dollars in payroll taxes.

The ability to leave bequests would be especially meaningful for lower-income workers. Not only do lower-income workers tend to have lower life expectancies, and therefore receive less in Social Security benefits than higher-income counterparts, but their families do not receive the same leg up from bequests that middle- and upper-income families often receive from their elders to pay for a grandchild’s education or to purchase a home.

After payroll taxes and other levies, there simply isn’t much left for lower-income workers to save for the benefit of their heirs.

A young male earning only half the average wage would have enough in a personal account to provide the exact same income that Social Security provides, and to also leave $479,000 to his heirs if he died at the average life-expectancy age of 76. Even if he were to live to age 90, he would have $270,000 left in savings to leave to his heirs.

Allowing workers to more easily save for their own needs today, and in retirement, instead of taxing them heavily to provide them with public benefits would enable workers to accrue higher retirement incomes in addition to greater take-home pay during their working years.

Supplemental Security Income benefits for elderly individuals who face poverty could provide a floor below which no worker would fall, but such income security benefits would require only a fraction of Social Security’s current payroll taxes.

Lawmakers need to act now—not only to address Social Security’s looming insolvency, but to reform the program in a way that reduces the tax burden on workers, leaving them with more money to pursue their goals today and to put toward personal savings.

Pairing Social Security reforms that limit the program’s size and taxes with universal savings accounts would help accomplish that goal by allowing workers to save, tax-free, for whatever purposes they want.

The American people, not Washington bureaucrats, should be the ones to decide how much and how best to save for their needs today and in retirement.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal