Although often brushed aside as the lesser of our nation’s entitlement problems, the Social Security and Disability Insurance Programs’ $13.4 trillion (and rising) unfunded liability demands substantial reform.[1] Raising the payroll tax cap (from its current level of $117,000) should not be an option. Raising, or even eliminating, the payroll tax cap would not solve Social Security’s financial shortfalls, but would impose economically damaging marginal tax rates on middle-income and upper-income earners. Such onerous taxes would reduce incomes and overall economic growth while generating very little net revenue. Furthermore, Congress would immediately spend any additional payroll tax revenue, leaving no improvement in future budget deficits, giving merely the appearance, on paper, of financial improvement in Social Security.

Social Security: Not Serving Its Original Purpose

Social Security was designed to provide income support to a relatively small percentage of the population: those who lived beyond the average life expectancy and were therefore less likely to be able to work or have sufficient savings. Life expectancy in the United States has increased by 17 years since Social Security’s inception, and medical advancements have allowed individuals to work longer.[2] Without corresponding adjustments in eligibility and benefits, however, Social Security has transformed into a potentially decades-long income subsidy for the masses.

In 1940, when monthly Social Security benefits were first distributed, less than 7 percent of the population was age 65 or older. Today, that figure has doubled to 14 percent, and by 2050, the share of Americans 65 and above will have more than tripled to 22 percent. Social Security simply cannot continue to finance lengthier retirements for a rising percentage of the population.

Furthermore, Social Security is not serving its intended purpose of preventing poverty in old age. Despite working and paying Social Security taxes for 35 years or more, some retirees do not receive enough Social Security benefits to keep them out of poverty. In 2012, nearly 4 million people—9 percent—ages 65 and older were living in poverty.[3]

Current Cap: Historically Consistent and Higher than Other Countries’. The current Social Security payroll tax cap is $117,000 for 2014. This cap covers approximately 83 percent of wages, with roughly 94 percent of all workers earning less than the cap.[4] Those who would like to raise the cap are pushing for an increase to cover at least 90 percent of all wages, which would more than double the current cap to about $240,000.[5]

There is little rationale for raising the cap to cover 90 percent of earnings, and even less reason to eliminate it completely. The creators of the Social Security program did not advocate a tax cap; rather, they recommended that everyone with earnings above three times the average wage be exempt from Social Security altogether.[6] These individuals would neither pay Social Security taxes nor receive Social Security benefits. This recommendation was likely rooted in Social Security’s original intent to prevent poverty in old age. Individuals who earn more than three times the national average are unlikely to need government-provided social insurance to keep them out of poverty in retirement.

The existence of the tax cap in its current form not only curtails excessively high and economically damaging marginal tax rates, it also prevents workers with very high incomes from receiving unnecessarily high benefits.

Those who endorse a 90 percent tax cap point to a single year—1983—when the Social Security tax cap covered 90 percent of earnings. But 1983 was an historical anomaly (caused by a significant increase in the tax cap in 1977). Since Social Security’s inception, the tax cap has covered an average 84 percent of earnings—nearly the same as the 83 percent of earnings the tax cap covers today.[7]

Not only is the current wage cap in line with its historical average, it is also significantly higher than the tax caps of other large, industrialized countries. In 2008, the United States’ Social Security wage cap equaled about 2.5 times the average wage, compared to 2.0 times the average wage in Germany, 1.5 in Japan, 1.2 in the U.K., and equal to the average wage in Canada.[8]

Cap Increase: Whose Taxes Would Rise?

According to a study by the liberal Center for Economic and Policy Research, if the payroll tax cap were increased to cover 90 percent of earnings or eliminated entirely, about 5.2 percent of workers would face an immediate tax increase.[9]

But this represents only a snapshot in time. A 2011 report by the Social Security Administration estimated that between 20 percent and 25 percent of individuals born after 1951 will earn above the taxable maximum at some point in their working careers.[10] This means that one out of every four workers would pay higher taxes over their lifetime if the cap were raised or eliminated.

Marginal Tax Rates Would Soar. Raising the payroll tax cap to cover 90 percent of earnings would amount to a massive tax increase on middle-income and upper-income earners.

A single person with $125,000 in earnings would see his combined federal income and payroll tax rate jump from 30.9 percent to 43.3 percent, and would pay an additional $1,400 in taxes. A single-earner married couple with two children and $125,000 in earnings would see their marginal tax rate jump from 32.9 percent to 45.3 percent, and would also pay an additional $1,400 in taxes. The marginal tax rate of a married couple with two children and two earners each making $125,000, would rise from 36.8 percent to 49.2 percent, and they would pay $2,800 more in taxes.

Marginal tax rates and total tax increases would be even more dramatic for those considered “rich” by President Barack Obama’s standards.[11] If the payroll tax cap were increased to cover 90 percent of earnings, the marginal tax rate for a married couple with two children and $400,000 in earnings would rise from 44.2 percent to 56.6 percent, while their total tax liability would increase by as much as $35,500.[12]

Adding on state and local income taxes would bring middle-income to upper-income tax rates well above 50 percent. In California, the state with the highest top income tax rate, a single-earner married couple with two children and $125,000 in total earnings would face a combined marginal tax rate of 54.6 percent.[13] Despite this family earning only half as much as the current Administration considers rich, 55 cents of every additional dollar that family earns would be taken away in taxes.

For those considered rich, adding on state and local income taxes would bring the top marginal tax rate in the United States to 70.3 percent (57.0 percent federal taxes and 13.3 percent California state taxes).

All taxes are distortionary, meaning they alter individuals’ behavior as well as total economic output. High marginal income tax rates are particularly distortionary for high-income, highly skilled workers. Whereas lower-skilled workers with lower incomes are constrained in their ability to cut back on work when marginal tax rates rise (because they must maintain some minimal level of income), more highly skilled, higher-income workers generally have more flexibility to work less when marginal tax rates rise. But when workers cut back on work and receive less take-home pay, they also tend to cut back on savings and investment. Less work, lower incomes, smaller savings, and less investment are harmful to economic growth, which in turn, is detrimental to tax revenues.

A Conduit for More Government Spending. Raising the Social Security payroll tax cap would create a double whammy for budget deficits. Not only would it reduce non–Social Security tax revenues due to lower incomes (caused by employers reducing wages in return for higher payroll taxes as well as workers’ behavioral responses), it would also result in higher government spending.

Multiple economic studies confirm that Social Security surpluses have not contributed to lower public debt, but rather to more non–Social Security government spending.[14] This is because Social Security surpluses have served as a means of financing other forms of government spending, to the tune of more than $1 trillion since Social Security’s inception, without having to borrow from the public and without recording an overall budget deficit. One estimate shows that as much as 100 percent of Social Security trust fund surpluses have been offset through higher non–Social Security government spending or lower taxes.[15]

If the payroll tax cap is increased or eliminated, it will provide an influx of tax revenues to the Social Security system, turning today’s cash-flow deficits into cash-flow surpluses. But those added revenues will not be put into a Social Security “lockbox.” Rather, the additional revenues will allow the federal government to spend precisely that much more without having to borrow from the public. Spending those new payroll tax revenues while also crediting them to the Social Security Trust Fund is double counting. Double counting is an accounting trick where the federal government essentially spends the same dollar twice. Higher payroll taxes could finance current spending, while at the same time extend the life of the Social Security Trust Fund. However, since the trust fund has no economic value, the government will have to borrow or raise taxes to pay benefits in the future. If added payroll tax revenues are used for higher spending, raising the payroll tax cap could actually increase, rather than decrease, U.S. debt.[16]

Raising or Eliminating the Cap Will Not Fix Social Security

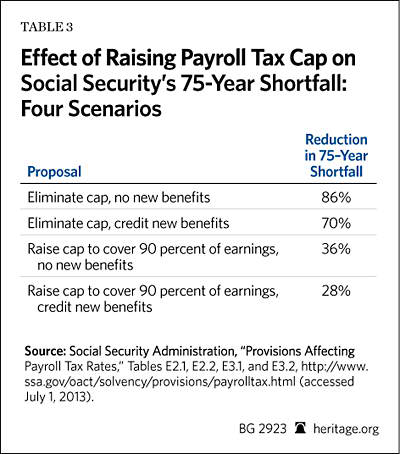

Despite claims to the contrary, raising or eliminating the payroll tax would not fix Social Security’s long-run financial imbalance. According to the Social Security Administration, even if the tax cap were eliminated completely and no new benefits were credited to those who pay higher taxes (fundamentally altering the contributory nature of Social Security), this massive tax increase would still fall $2 trillion short of eliminating Social Security’s estimated 75-year actuarial deficit (an improvement of 82 percent).[17] Furthermore, the improved solvency from eliminating the payroll tax cap would be front-loaded, providing annual cash-flow surpluses until 2024, followed by endless and growing deficits in the out years. By 2088, Social Security’s annual cash flow deficit would equal more than 2 percent of taxable payroll (an improvement of 55 percent compared to not eliminating the payroll tax cap).[18]

Less aggressive options would do even less to solve Social Security’s shortfalls: Eliminating the cap while crediting those who pay higher taxes with higher benefits would provide cash flow surpluses until 2024 and would leave $3.6 trillion of Social Security’s 75-year actuarial deficit unresolved (an improvement of 66 percent); raising the cap to cover 90 percent of earnings without increasing benefits would fail to generate a single year of cash-flow surpluses while leaving $7 trillion in deficits (an improvement of 34 percent); and raising the cap to 90 percent and increasing benefits would also not produce cash-flow surpluses and would leave $7.8 trillion in Social Security’s 75-year actuarial deficit (an improvement of 27 percent).[19 ]

Again, these smaller financial improvements would be front-loaded. By 2088, the annual cash-flow improvements would be: 36 percent for eliminating the cap and increasing benefits; 24 percent for increasing the cap to cover 90 percent of earnings without increasing benefits; and 14 percent for increasing the cap to 90 percent and increasing benefits.[20]

But these figures represent static revenue projections, which assume that neither employers nor employees who face higher taxes will alter their behavior. In reality, employers will reduce employees’ wages (including shifting some compensation to untaxed benefits) and employees will alter their work effort. These changes will reduce static revenue projections.

How Much Revenue Would There Really Be? It is easy to estimate how much new revenue might be raised by increasing the taxable maximum—this is a simple multiplication of earnings above the “tax max” times the 12.4 percent payroll tax rate—but, estimating how much revenue will be raised after employers shift incomes and employees change their behavior is more complicated.

For starters, there are behavioral effects, such as workers choosing to work less and employers shifting compensation to untaxed benefits, which reduce tax revenues. The degree to which revenues decline depends on the magnitude of behavioral responses from those affected by the tax increase. Under a relatively low wage elasticity of 0.2, the net revenue gain—including Social Security, Medicare, and other federal and state income taxes—from raising the Social Security payroll tax cap to cover 90 percent of earnings would be only 52 percent of the static revenue projection.[21] In other words, for every dollar of new revenue credited to Social Security as a result of raising the payroll tax cap, 48 cents in combined federal and state taxes would be lost, resulting in a net revenue gain of only 52 cents.

Many economists have found that marginal tax rate elasticities are much higher than 0.2, particularly for high-income earners. Economist Martin Feldstein, for example, considers an elasticity of 0.5 for middle-income and high-income earners to be a reasonable, if not conservative estimate, based on existing studies.[22] Under an elasticity of 0.5, economists Jeffrey Liebman and Emmanuel Saez found that the net revenue increase from raising the payroll tax would fall to just 10 percent of the static revenue projection.[23] In other words, for every dollar of new revenue that static estimates credit to Social Security as a result of raising the payroll tax cap, 90 cents would be lost in combined federal and state taxes, leaving only 10 cents in net revenue.

With an elasticity of 0.5, raising the payroll tax cap would approach the revenue-maximizing Laffer rate, meaning the higher taxes could actually reduce, rather than increase, net tax revenues. Indeed, as Liebman’s and Saez’s estimates show, with an elasticity of 0.8, raising the payroll tax cap to cover 90 percent of earnings would result in a net decline in tax revenues of about one-third the static revenue projection.[24]

Aside from behavioral effects, there is also the direct-incidence effect. Standard economic assumption is that employees bear the full burden of employer-paid taxes through lower wages.[25] Thus, when employers are faced with an additional 6.2 percent tax on wages above the current tax cap, they will reduce affected wages by that amount. Lower wages not only reduce the amount of new Social Security tax revenue, but revenue from Medicare taxes, and federal, state, and local income taxes as well.

Setting aside all potential behavioral effects, Liebman and Saez estimate that incidence shifting would reduce actual net revenue gains by 20 percent if the tax cap were raised to cover 90 percent of earnings and by 24 percent if the cap were eliminated completely.[26]

The Social Security Administration estimates suggest that raising or eliminating the payroll tax cap could solve anywhere from 28 percent to 86 percent of Social Security’s 75-year actuarial deficit and generate cash-flow surpluses until 2024. However, even conservative estimates of behavioral responses and incidence shifting suggest that net revenue gains from increasing or eliminating the payroll tax cap would be far less than 50 percent of static estimates, and stronger effects could actually reduce net tax revenues.[27]

Conclusion

Social Security is an insolvent program that demands immediate reform—but raising the payroll tax cap should not be an option. Static revenue projections conceal the true impact of raising the Social Security payroll tax. What may seem like an easy way to improve the program’s long-run finances would, instead, reduce incomes, slash non–Social Security tax revenues, stimulate higher government spending, and do little to improve Social Security’s solvency.

Policymakers need to reform Social Security now, curbing costs and returning the program to its original intent of preventing poverty in old age. Raising the payroll tax cap would increase costs, move the program further from its original goals, and hurt individual incomes, tax revenues, and economic growth in the process. Raising the cap is a lose-lose move.

—Rachel Greszler is Senior Policy Analyst in Economics and Entitlements in the Center for Data Analysis, of the Institute for Economic Freedom and Opportunity, at The Heritage Foundation.