We live in a fallen world. Because man has a corruptible heart, when he is given a position of authority, he tends to amass more and more power for himself.

The father of the U.S. Constitution, James Madison, summed it up, “The truth [is] that all men having power ought to be mistrusted.”

Because the Founding Fathers rightly feared the tyranny that follows when any one person or any one branch of government has too much power, they designed a system of government centered around checks and balances.

The U.S. Constitution limits and divides federal powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. They expected that each branch, wanting more power for itself, would resist moves by the other branches to centralize and amass power.

As Madison explained, “You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself.”

The Bill of Rights also limits federal power by clarifying that all powers not directly given to the federal government are reserved for the states or the people.

The checks and balances devised by the Founders have helped restrain the power of the federal government for over 230 years, but “progressives” have gradually and effectively chipped away at many of those constraints.

The left has elevated executive branch agencies to the point where they now effectively make many laws, instead of simply executing the laws passed by Congress. The left has also greatly expanded and empowered the federal government at the expense of the states. The list goes on.

There is, however, one check against the excesses of government that is—at least for the moment—stronger than it was two centuries ago. Tax competition between nations acts as a much-needed check against the growth of the federal government.

Because people and money can flow more easily across borders today than in the days of long, dangerous ocean voyages, national governments must compete against each other on tax, spending, and regulatory policy. Today, governments that impose excessive taxes risk driving people and money out of their country (or state).

For example, some European governments sought to tax people’s wealth in the 1990s and early 2000s, only to end up with less tax revenue than they started with, not to mention a stunted economy and a less wealthy citizenry. Most of the countries eventually abandoned these damaging taxes. Even government leaders who favor relentless growth of government must face the cold, hard political realities when the promised tax revenues fail to materialize.

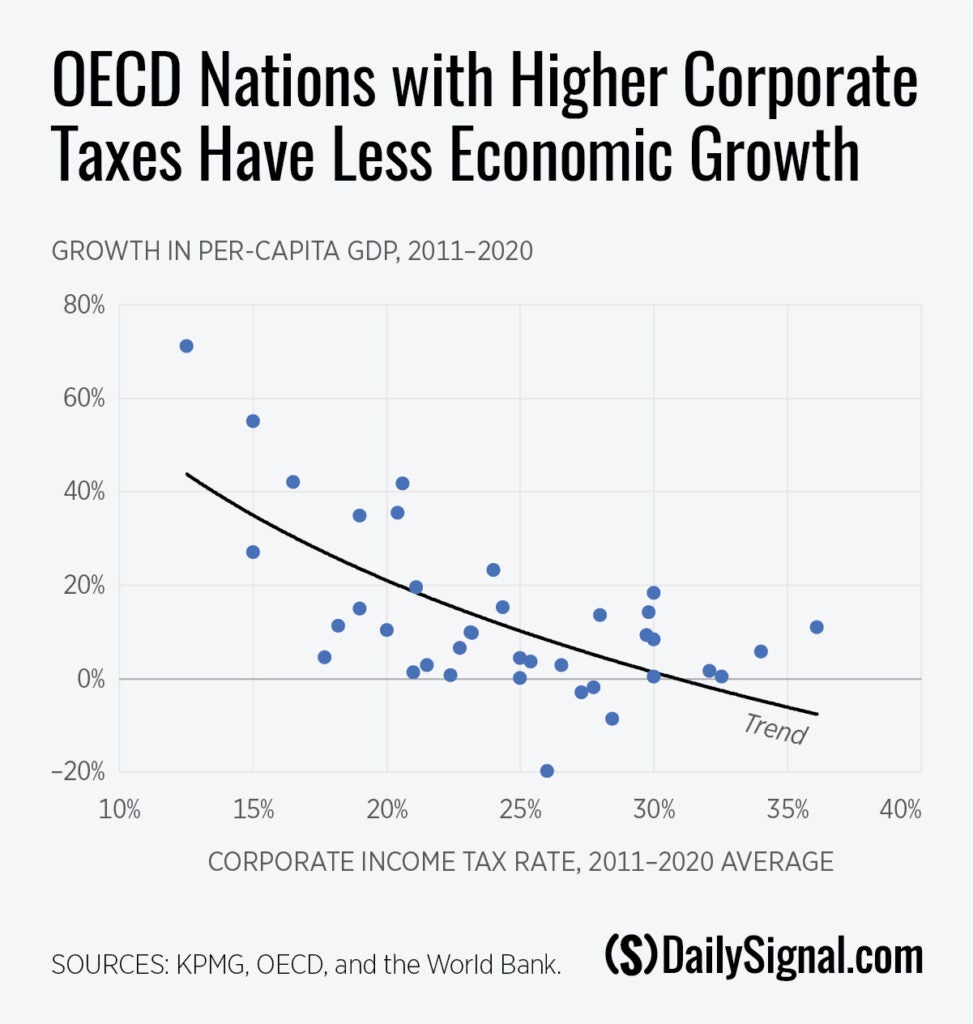

Tax competition is most clearly seen in the history of corporate income taxes. With the rapid rise of global financial markets in the 1980s, investors could easily invest in companies around the world. Unsurprisingly, people invested more in companies located in countries where corporate profits weren’t slapped with massive taxes.

But until the 1980s, most countries did slap massive taxes on corporate income. The worldwide average corporate income tax rate was about 40% in the early 1980s. That’s not including capital gains taxes and other taxes that allowed many governments to claim most of investors’ pre-tax returns.

As national governments witnessed their low-tax neighbors benefiting from the strong economy and good jobs that come along with business investment, they followed suit. The average worldwide corporate tax rate fell rapidly starting in the mid-1980s, falling from 40% to less than 28% by the mid-2000s. Today, the global average is about 24%.

Corporate taxes are a hidden tax on workers. After countries lower their corporate tax rates, residents enjoy stronger economic growth. Workers benefit the most from corporate tax cuts as real wages and employment rises with the influx of investment.

Most recently, the United States experienced strong growth after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which brought U.S. corporate tax rates down to a level only a couple points above the global average. Workers’ real weekly earnings grew as rapidly after the tax cuts as at any point in generations.

Unfortunately, since 2020, U.S. lawmakers have spent money like never before in peacetime history, launching the national debt from $23 trillion to over $30 trillion in just two years. This, along with an onslaught of federal regulations in the last year, has led to 40-year high inflation that skyrocketed from 1.4% at the start of 2021 to 7.9% today.

Worldwide, corporate income tax rates aren’t falling as quickly today as in recent decades. Indeed, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—with the support of the Biden administration—is leading a global push to bully countries into raising business taxes.

Under the organization’s convoluted global tax agreement, if low-tax countries don’t raise taxes on multinational businesses to at least 15%, they will effectively forfeit part of their taxes to high-tax countries. A global minimum tax provides cover to government leaders that wish to push their own taxes much higher.

Make no mistake, if businesses around the world pay higher taxes, consumers will pay higher prices, workers will take home lower real wages, and retirees will see their pension wealth decline.

Of course, if a 15% global minimum tax takes effect, how long will it be until there are calls to raise that minimum tax higher? How long until there are calls for other global minimum taxes? When do government leaders ever decide, of their own accord, enough is enough?

Tax competition is another obstacle against big government overreach that the left wants to neutralize. There are differences, to be clear, between tax competition and constitutional checks and balances like the presidential veto or the division of Congress into two houses. Tax competition is simply a favorable natural consequence of living in a global economy.

However, for those that care about individual liberty and limited government, tax competition is an important bulwark against the inexorable growth of government, not just in the United States but around the world.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal