The Constitution of the United States has endured for over two centuries. However, our constitutional republic is threatened by vulnerabilities in the election process, corruption amongst our elected leaders and representatives, and censorship of political speech that is fundamental to a free society. Our republican form of government is further weakened by misinterpretations of the Constitution that diminish our rights, dilute the separation of powers, and delegate legislative power to the administrative state. The very meaning of what it is to be an American—replete with our exceptional political, economic, and social culture—is now threatened by massive, uncontrolled illegal immigration. How do we remedy these problems, strengthen our constitutional republic, and restore the promise of America?

Introduction

Richard W. Graber

I’m Rick Graber, President of the Bradley Foundation, and on behalf of our team and our board of directors, it’s my great pleasure to welcome you to the Bradley Foundation’s annual symposium here in our nation’s capital.

Special shout out, of course, and thanks to Kay Cole James and her team at Heritage for once again hosting this event and for assisting in all of the logistics that go into events such as this. You are a true pleasure to work with, the entire team here at Heritage.

Also, a heartfelt thanks to Dianne Sehler from our Bradley team.

Some of you know Dianne will begin a well-deserved retirement in June. She’s been the primary organizer of this event for the past couple of years and for decades has led our higher education portfolio at Bradley.

Dianne, thank you once again for all that you’ve done for the Foundation over these many years. Thank you.

As most of you know, today’s a big day for us at Bradley. It’s Bradley Prizes Day, during which we have the privilege of bestowing upon three or four extremely worthy people our annual Bradley Prize. At Bradley, we focus our grant-making on organizations that are dedicated to our constitutional order, that are committed to free markets, that are dedicated to the formation of informed and capable citizens, and that are committed to the fundamental institutions of our civil society. Our Bradley Prize winners reflect and embody those principles in their daily work, and our goal for this symposium is to shine a spotlight on at least one of those principles during this day of celebration.

I’m quite confident that we’ll accomplish that goal with today’s lineup of distinguished panelists, and of course, our moderator, Hans von Spakovsky.

Hans is a senior legal fellow and manager of the Election Law Reform Initiative in the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies here at Heritage. He’s a well-recognized authority on a wide range of issues, including civil rights, elections, the First Amendment, immigration, the rule of law, and government reform. He served on President Trump’s Advisory Commission on Election Integrity and was a member of the Federal Election Commission—among many, many other responsibilities.

Hans is a graduate of Vanderbilt Law School and M.I.T., and we are delighted that he has once again agreed to serve as moderator for this event.

So, without any further delay, let me turn it over to Hans to introduce our topics and our panelists for today’s session.

Richard W. Graber is President and CEO of The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

“A Republic, If You Can Keep It”

Hans von Spakovsky

Welcome to the Heritage Foundation and the 2019 Bradley Symposium, “The State of the Constitution.”

The governing document of our great republic was signed on September 17, 1787, by 38 of the 41 delegates present at the Constitutional Convention, after three months of debate. All of you have heard the very well-known story of Benjamin Franklin who, as he was leaving the Convention, was approached by a group of citizens who asked him what kind of government had the delegates put together. His answer was, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

That warning by Franklin is what we are here to discuss today: whether we are losing our republic and what we can do to keep it.

As the introduction in the program for the symposium says, our constitutional republic is threatened by everything from security vulnerabilities in our whole election process, to corruption, to a rise in censorship in the political and cultural speech that’s fundamental to a free society. Many of our liberties are also being eroded by an ever-growing national government, far larger and more powerful than anything the delegates to the Constitutional Convention could have imagined in their worst nightmares.

That includes a vast administrative state stocked with a bureaucratic swamp that is unanswerable to voters and unaccountable to the public. The creation of that Fourth Estate is due to members of Congress—regardless of political party—delegating vast swaths of their constitutional authority to federal agencies to an extent, again, that I do not believe that the convention delegates, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, or George Washington, could possibly have foreseen.

Our republic has been further weakened by judges who misinterpret the Constitution and, most importantly, fail to apply the limits on the power of the federal government that are hardwired into the document.

All of you recall that Ronald Reagan said “Preserving our freedom is something that must be fought for and protected in every generation.” While our Constitution is probably the greatest political document ever created in human history to provide the structure for a government dedicated to liberty and economic opportunity, it is not a self-actuating document that can protect itself. It requires an independent, educated, moral people who not only have a political, historical, and cultural understanding of the importance of the Constitution’s origin, the rights it protects, and the limits it imposes on government, but it requires a people who are dedicated and devoted to protecting it.

Such a society is difficult to preserve when many members of the public show an alarming and shocking ignorance of the Constitution. It is also hard to preserve such a society when a country cannot control its borders, and its very economic, political, and social fabric is threatened by massive, uncontrolled illegal immigration.

We are a country built on legal immigration, based on a patriotic assimilation model, in which we have welcomed immigrants of every color and creed from all over the world, as long as they agreed to become Americans once they arrived here. Not hyphenated Americans, as Teddy Roosevelt warned. They agreed to accept the responsibilities of living in a constitutional republic, not just its benefits.

That unique cultural heritage that has provided the glue that has tied us together as one nation, one people, is being destroyed by those who want to divide us and to separate us, to make us cling to group identities that have nothing to do with making us a great people, but everything to do with seizing political power at the expense of E pluribus unum.

Hans von Spakovsky is Senior Legal Fellow and Manager of the Election Law Reform Initiative in the Edwin Meese III Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at The Heritage Foundation;

I. The Process Threats to the Republic: Fraud, Corruption, and Censorship

Election Fraud: Gaming the System

J. Christian Adams

We gather again to discuss the state of the Constitution. I’d wager that today’s audience has divergent expectations.

To some of you, today’s event is one in a series of familiar Washington events where interesting and thoughtful discussion will occur, and the ramifications and insights will be confined largely to internal intellectual stimulation. In other words, this morning you were expecting an exercise to catalog some fascinating academic ideas about the Constitution.

To others here today, this symposium can barely keep up with the intensifying destruction of bedrock Western values, engineered and managed by the Left, in conference rooms and collaborative open-floor plans, with cubicles, at outfits like Arabella’s Advisors, the New Venture Fund, the Democracy Alliance, the Media Consortium, the Climate Resistance Fund, and so many, many others.

In other words, the state of the Constitution is one of immediate crisis, with progressive groups no longer interested in debating ideas, but engaged in open, unashamed, and hyper-funded efforts to destroy the Constitution and replace our system of limited government with their utopia. The Constitution stands in the way of their utopia for now. But the progressive Left cares about process as much as, or perhaps more, than policy.

What do I mean by “process”? The rules. Who votes? When do you vote? How do you vote? How do you fund campaigns? Who decides election rules? That is process.

Election Process and the Aggressive Left. Consider the election process, the area where my group, the Public Interest Legal Foundation, is most active. I will have more [to say] on elections being corrupted later in the talk. But for now, consider efforts to destroy the Electoral College system put in place by the Founders. Federalist 68 said the Electoral College prevented “[t]umult and disorder.”REF I could use all of my time here to discuss why the Electoral College is so important. But our foes have moved well past the debate into the wrecking phase through the National Popular Vote Movement.

The National Popular Vote Movement is nothing short of an effort to dissolve the Union of 1787. And, so far, what has been our response? Debates with proponents? Lectures? Opinion page editorials? A very thoughtful paper? I would submit that the institutional Left is intensifying efforts to deconstruct the Constitution and our system of limited government.

In just the last decade, the Left has grown exponentially more muscular, more aggressive, and even more violent. They have adopted tactics consistent with their pedigree, such as denunciations, as practiced by the Southern Poverty Law Center; deplatforming groups like the NRA [National Rifle Association] or James O’Keefe from financial services; and utilizing the powers of the state to target organizations who support limited government. And they have built hyper-funded redundant infrastructures to target, smear, and sue those who defend the Constitution and limits on government power.

They are behaving like their utopian forefathers who authored so much of the 20th century’s history. These utopians who hate the Constitution seek openly to end airplane travel. And why not? After all, they enjoyed great success in their attacks on coal. The utopians are redefining hate and bigotry in ways that smear mainstream Christian and Catholic theology. These utopians are spending hundreds of millions of dollars to create a new culture that erases American ideals: a culture that rejects home ownership and driving a car; hates [the] fossil fuels that led to an explosion in human standards of living; promotes communal dining, preferably without beef; blurs birth gender; and elevates environmental stewardship to a pseudo-theology.

They hate our republican form of government and seek to transform election process rules in ways to restructure our system of government.

They have blown right through the firewalls that we thought would protect us, such as the notion that they would go too far and cause a backlash.

I would argue that their race to the extreme has only attracted more recruits to their cause. We forget how attractive extremism was in the 20th century, when those longing for purpose and meaning in their lives were attracted to extreme causes.

One Generation? When Ronald Reagan spoke to the Chamber of Commerce in Phoenix in 1961 and said that freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction, I suspect many in the room here today, when you heard that, found it to be a gentle and benign overstatement. For much of my life, so did I. But those of us who watch and monitor the Left, who oppose them in courtrooms and legislatures, on television, [and] on radio, have seen an unmistakable and worrisome intensification. They have grown more muscular, more aggressive, more well-funded, and most troubling, more open about their plain intentions. I’m afraid that Ronald Reagan was right. One generation is all it could take.

Yet we have this consolation: The contest is squarely within the line of other 18th, 19th, and 20th century history, characterized by utopians versus defenders of individual rights. Even my area of election law is dominated by noisy utopians. They’re obsessed with changing process rules. They believe if they change how elections are conducted, their utopian policies on everything else you care about will be enacted: energy, rule of law, property rights, free exercise, free speech, education, labor. Their priorities will be enacted as policy.

In other words, the Left views changing election process as the way to change the country’s policy.

Don’t take my word for it. Listen to what they say. All of the below organizations I’m going to name are active on election-process issues relating to reviving the federal preclearance portions of the Voting Rights Act.

Here we go: Greenpeace; the Service Employees International Union; the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees; the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws; the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund; the League of Conservation Voters; the Freedom Socialist Party; the National Education Association; and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

What? The Union of Concerned Scientists cares about voting issues? Didn’t they exist just to harass Ronald Reagan when he was proposing the Strategic Defense Initiative?

This is from their website, where they claim that there are: “increasing barriers to voting, including felon disenfranchisement and restrictive rules on both registration and the ability to get to the polls.”

That’s the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The Left and Non-Citizen Voting. The Left advocates seemingly innocuous changes to election laws to benefit their proposed policy organizations. Consider Motor-Voter. Passed in 1993, Motor-Voter was supposed to give you the right to register at driver’s license offices, but instead now reaches such things as social service agencies and even methadone clinics. And so, what you have is a citizen checkbox in Motor-Voter: That [checkbox] is the only thing preventing noncitizens from getting on the rolls.

Meanwhile, the Left denies that there are even noncitizens on the rolls, and I’ll show you in a moment some evidence regarding that. When states try to fix the problem, like Kansas, Georgia, and Alabama, they are promptly sued by some of these Left-wing groups.

Now, let me show you some slides. How can [illegal] aliens possibly get on the voter rolls? That’s not something that should happen.

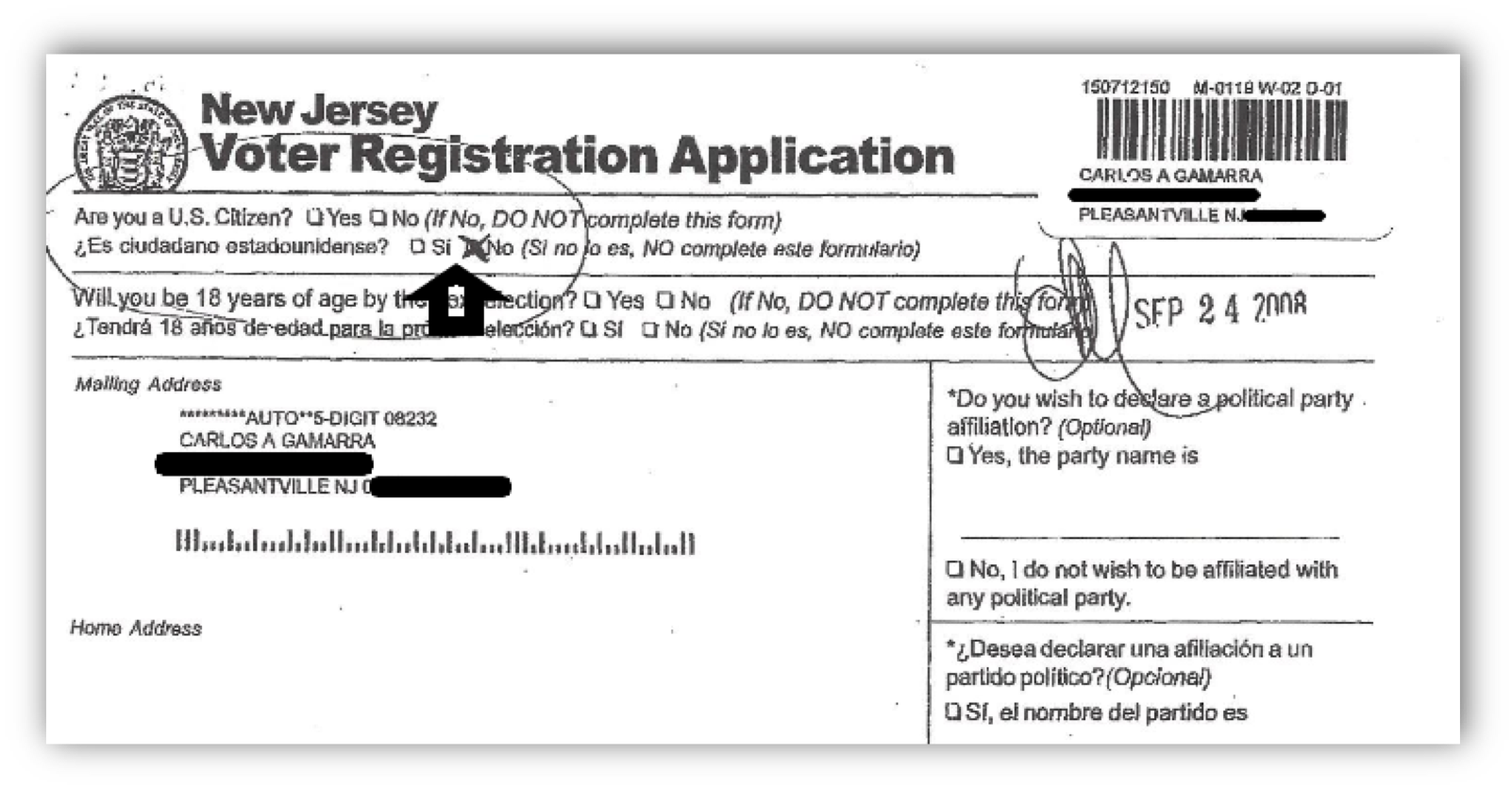

The Public Interest Legal Foundation has sued to collect voter records. What we’ve been doing is going around the country and collecting voter records relating to vulnerabilities in the system. And this is one. This is a New Jersey voter registration form. And you’ll see the question, “Are you a citizen of the United States?” And the applicant marked “No,” as you can see—but yet was still registered to vote.

Now, this is not a one-off. I could stand here for an hour and scroll through slides just like this all around the country that we’ve gotten.

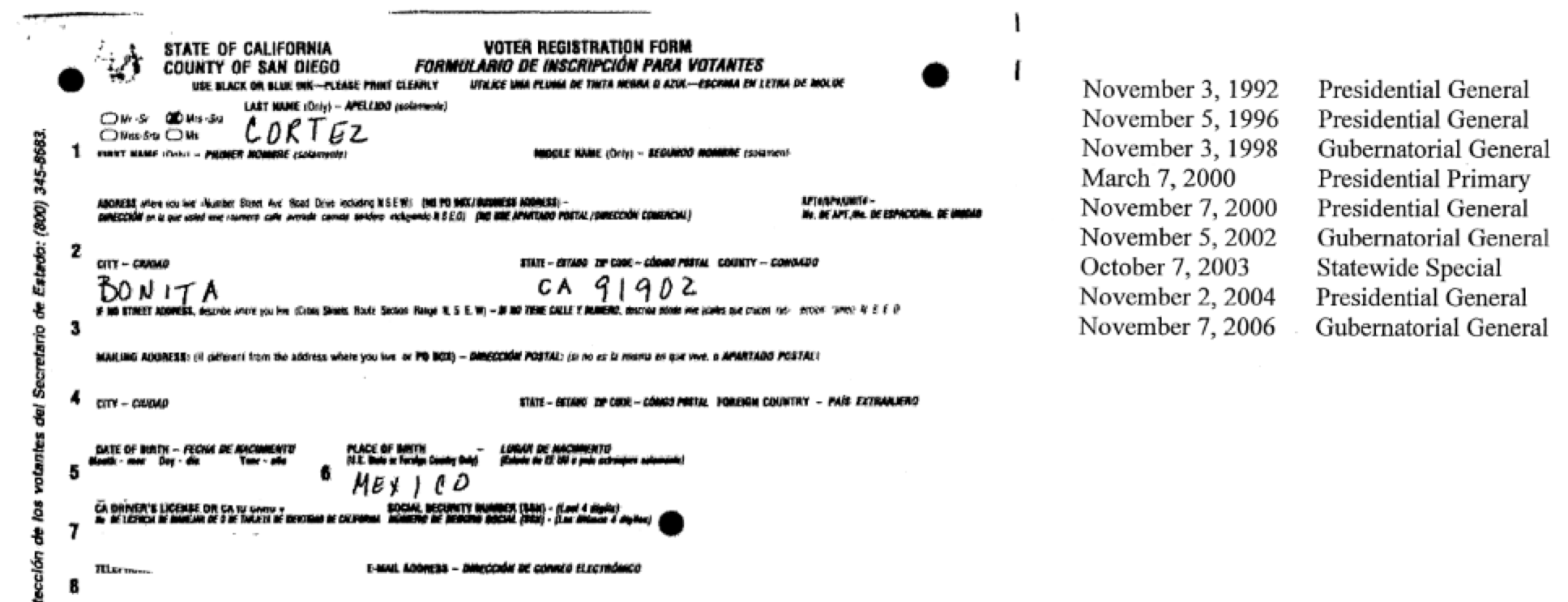

But are they actually voting? Here we have another voter registration form from another noncitizen, Mr. Cortez. Now we can see his voting history. The record was only created because Mr. Cortez wanted to naturalize. And when Mr. Cortez wanted to naturalize, he needed to clean up his act. INS [Immigration and Naturalization Services] said, “You need to make sure you’re not registered to vote.” So, Mr. Cortez wrote and created a record that we were able to capture in our searches that also showed his voting history.

I’m just going to make an assumption: Bill Clinton, Bill Clinton, Al Gore, John Kerry, and Gray Davis. You get the point. This is from California.

He is not the only ineligible person that was registered to vote in California. You get a sense now how California has been so radically transformed in the last 20 years. Things are so crazy in California you can’t go out in public without signs everywhere warning you that you’re going to catch cancer if you take one more step forward.

And if you do take one more step forward in San Francisco, you should be very careful where you step.

Process and Policy. See now how process and policy interact. When you have vulnerabilities like this in the system, you can transform a state.

Let me show you another state. This is an individual who was registered to vote in Michigan. Again, you can see his voting history. He’s a noncitizen. And he said, “I just received a voter registration card in the mail, but I’m not a citizen.” And he seemed shocked. We can see a long, detailed voting history for this alien.

Remember, these are only the aliens who are self-reporting that we’re getting the records from. Sort of like self-deporting, this is self-reporting to the election officials. These are just several examples of hundreds that we have found in our litigation research around the country. And believe me, this is exactly what the Left wants to be happening—because they fight it in the courtrooms anytime someone tries to fix it.

In closing, I fear the Constitution will suffer increasing attacks by this new muscular Left who wants to do away with it. And they say so. The Left has adopted aggressive tactics, and our job is to develop new ways to hit back and to defend the treasure that was created in 1787. If we keep responding the way we did 20 or 30 years ago, we risk losing this precious treasure given to us.

J. Christian Adams is President and General Counsel at the Public Interest Legal Foundation in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Secret Empires: The New Corruption

Peter F. Schweizer

I’m going to talk a little bit about the threat that corruption poses to the U.S. Constitution. And I’m going to talk about it not to minimize the issues that Christian [Adams] is talking about or the other issues that will be raised here today, but because corruption is often overlooked, as opposed to the ideological threats to the Constitution.

Complexity and Bipartisanship. It’s overlooked for a couple of reasons. First of all, it’s complex. It can be difficult to evaluate. But second of all, because it tends to be a bipartisan problem. The money flowing through Washington D.C. does not just touch Democrat hands. It touches both political parties. And to look at the amount of money flowing through Washington D.C., let me just give you sort of an illustration.

I did a special for Fox News a few years ago, “Boom Town,” on how Washington D.C. was becoming this wealthy town. One of the things we did on this segment is we interviewed a guy who works for Ferrari of Washington D.C. There’s a Ferrari dealership in town, and we said, “How’s business?” And he said, “Business is great, but there’s a problem.” We said, “What do you mean? What’s the problem? If business is great, how can there be a problem?” He said, “Ferrari of North America is upset because in South Beach where we have a dealership and in Beverly Hills where we have a dealership, when people buy cars, they finance them. And Ferrari of North America wants you to finance your car purchases. When they buy Ferraris in Washington D.C., they pay cash.”

Now, I’m not opposed to making money. I believe in the free market. But when you talk about government corruption, you’re no longer talking about the free market. And what I’d like to do is talk about a couple of examples of corruption that exist today, and then explain briefly why I think this is a central issue.

The Rise of the Princelings. First, let me talk about the rise of America’s princelings. I’m going to take you back to December of 2013 when Vice President Joe Biden was flying on Air Force Two for a series of meetings in Asia, particularly to Beijing, China. On the plane with him was his son, Hunter Biden. Joe Biden had a series of meetings. By a lot of press accounts, the Washington Post’s and others, Joe Biden was relatively soft on the Chinese. Ten days after they returned, Hunter Biden’s small boutique investment firm, called Rosemount Seneca Partners, procured a $1 billion private equity deal with the Chinese government. Not with a Chinese corporation, not with an American company in Beijing, China—but with the Chinese government itself. It was rapidly expanded to $1.5 billion, and it was the first of a series of deals that the son of the Vice President procured with the Chinese government.

Well, isn’t that just sort of free market activity? I would contend no. First of all, Joe Biden was the point person on Obama Administration policy towards China, which means he made crucial critical decisions. Point number two: Hunter Biden had no background in private equity, and he had no background in China.

The question is: What was going on? If you look at the Chinese literature, it’s pretty clear. The Chinese believe that American politics can be cracked in the way that Chinese politics operates, namely through princeling arrangements. For anybody doing business in China, they know that to get business done with a Chinese minister, it’s good to hire the son or daughter of that minister as a consultant.

This is the rise of the princelings. This is not unique to China, and this is not unique to Joe Biden. This is a growing phenomenon that we see in Washington D.C., where family members become integral parts of self-enrichment, biopolitical leaders in the United States. The reason it occurs is because government officials in Washington D.C. have increasingly more power. More power means they can pick winners and losers—and that means that there are people around the world willing to put money in their pockets to get what they need.

Let me talk about a second phenomenon briefly, and that is the problem of extortion.

The Problem of Extortion. A lot of people have the image of corruption in politics. They go back to the great movie, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” with Jimmy Stewart. You all remember the great movie. In this story, essentially, the problem was you had this idealistic senator who was appointed, who wanted to do these wonderful things, but these outside corrupting factors just simply eventually were going to wear him down. In other words, the traditional view of corruption is that public servants are idealistic, they want to do the right thing, and you have all these outside nefarious forces that are trying to bribe them and corrupt them.

Certainly, that takes place. Although, I think oftentimes it’s more an extortion model, where the public official is trying to create a demand for their own services, which leads to an extortive relationship. Let me just give you one example. This is what I call “mud farming” in Washington D.C.

Dodd–Frank and the Mud Farmers. Anybody that reads William Faulkner might be familiar with a novel he wrote years ago called “The Reivers.” In that story, it recounts the main character going along this dirt road in a car. He quickly realizes that there’s a family that lives by the road that at night will go up and plow the road and bring in buckets of water, creating mud. The next day, they wait by the side of road with a team of horses so that when people’s cars get stuck in the road, they charge an exorbitant fee to pull them out of the mud that they created in the first place. That’s a little bit how this process works in Washington D.C., and there are lots of mud farmers. Let me give you one very prominent example, and this is a huge problem in all sorts of areas.

Go back to the Dodd–Frank rules on financial regulation. Anybody here in the private sector, financial sector? People are probably familiar with Dodd–Frank. Dodd–Frank, when you count all the rules, is a piece of legislation that is about 10,000 pages long. This is the first revision to financial markets since Glass–Steagall in the 1930s. Glass–Steagall was about 36 pages long.

How did we go from 36 pages to 10,000 pages? Yes, our financial markets are more complicated. But they’re not that much more complicated. What we have in Dodd–Frank is a document that Warren Buffett and the brightest minds on Wall Street say they cannot understand. It’s my contention that that’s precisely what it’s designed to do.

What do I mean by that? All you need to really know is what happened to the people that actually wrote the Dodd–Frank bill. What actually happened to the congressional staffers who wrote a bill that people could not understand? After Dodd–Frank was passed, they quit their jobs, and they opened up a consultancy firm doing what?

Compliance.

Yes. Interpreting the law that they had written for Wall Street financial firms. The walk-in fee was $100,000. That was the walk-in fee for that kind of advice.

My point here is simply this: The complexity that we see in laws, rules, and regulations in Washington D.C., I would contend, is less an issue related to the complexity of the modern world. It has more to do with a business model in which bureaucrats, congressional staffers, and decision makers want complexity. They don’t want simplicity. They want complexity because it can be monetized. And it is being monetized.

Conclusion. In closing, what does this mean as regards to the Constitution? I would say it means everything, because the representative government that our Founders intended was a representative form of government that we could understand, with which we could interact. That we would have clear representation by our leaders. They might not make the decision that we always want, but by-and-large, their interests would be those of their constituents back at home and upholding the U.S. Constitution.

What corruption has done, what self-enrichment has done, is created a circumstance where you have in effect a bipartisan machine in Washington DC, in which individuals can self-enrich by undermining those basic precepts of the Constitution.

Peter F. Schweizer is Co-founder and President of the Government Accountability Institute in Tallahassee, Florida.

The Constitutional Crisis of Free Speech on Campus

Allen C. Guelzo

If freedom of speech is one of the bedrock principles of a democratic republic, then surely nothing wears a more depressing aspect for the future of that republic than the ugly outbursts of free speech suppression that have become increasingly common on American university and college campuses.

Campus Assaults. Unless we lack either eyes or ears, we have witnessed over and over again to violent shout-downs (as at Middlebury College), harassment (as at Sarah Lawrence College), dis-invitations (23 of them so far in 2019), and outright riots over political issues and personalities. So much so that President Trump has felt impelled to issue an executive order threatening institutions that permit or practice such silencing with the withdrawal of federal funding.

These incidents have a far more ominous form than mere halftime hijinks: They arise from impulses more deliberate than momentary umbrage taken at a speaker’s opinions. The exercise of any right, constitutional, statutory or natural, has always run the risk of triggering painful—sometimes literally painful—responses. But in such cases—a ripe tomato in the speaker’s face or a ripe fist aimed at the speaker’s jaw—we are usually talking about the emotional tinder of the occasion, and such incidents can be treated as violations of criminal statutes concerning assault and battery.

A Dual Threat. What has made the recent rash of campus collisions over free speech much more troubling is two-fold. First of all, their intellectual justification, and how carefully orchestrated they have been under the rubric of a public philosophy that regards rights as an illusion, and thus serves to instruct communities of young American learners (either by example or by precept) in contempt for the American constitutional order. Secondly, their location within the circle of the university, and how flagrantly these encounters throw to the winds the very purpose of the university, a purpose older by centuries and civilizations than the constitutional order itself.

Neither of these new twists presents itself in the company of an easy solution. Freedom of speech is nestled in the First Amendment and bars Congress from passing any laws “abridging the freedom of speech.” Straightforward as that seems, it actually has a checkered history, since the ban on abridgments of speech was often understood until the 20th century to be a limitation on Congress alone, thus leaving the states and private institutions to sort out under their own roofs what speech would be considered free and what not. Moreover, the defense of free speech was often narrowed if it could be shown that such speech led to a “bad tendency.” Not surprisingly, modern restrictions on campus speech have been defended on these same grounds.

University speech codes, it is argued, are imposed by private actors, not publicly funded ones and enjoy the same protection private employers would enjoy if they fired employees who bad-mouthed the boss. Other defenders of speech codes argue that some speech has a “bad tendency.” It either inflicts emotional harm on certain hearers or has the potential to incite or protect others in bad behavior.

Line of Separation? To be candid, there is a difficulty posed by the fact that no bright line exists between speech and action. If speech could be made to stand alone and purely in the abstract, there might be less reason to object to objectionable speech. But speech and action all-too-often flow together. So, it is not an illegitimate question to ask whether speech that generates harms should enjoy the same protection as speech that prefers Bach to Mahler.

These ambiguities have provided a convenient opening to arguments that certain speech and certain speakers may be suppressed (especially on university campuses). Because the university has the right to police speech on its own private turf, and because some speech may indeed provoke harmful results—not actual murder and mayhem perhaps, but certainly psychological wounding, cognitive unhappiness, and those speaking of what should be unspeakable, all of which produce trauma.

This in turn costs the university money, whether in the form of creating so-called safe spaces and elaborate counseling programs, or safety and police costs that the university is entitled to act upon in its own self-interest.

There is a surface plausibility to each of these responses—and in both instances it is wrong. Yes, each of the colleges and universities that I mentioned at the beginning are private institutions. But not even private institutions—not even private employers—are authorized to punish political speech or to behave as though the Constitution somehow stopped at some boundary around their campuses. Yes, speech and action have no bright line of separation. And yes, speech can lead to reckless incitement (as in Justice Holmes’s famous example in Schenck v. U.S. of shouting “fire” in a crowded theater).REF

But in the arguments made in defense of the suppression incidents I listed earlier, there was no attempt made at recognizing that there is no bright line between speech and action: Instead, the argument is made that there is no line whatsoever. Speech is violence, and silencing it is justified as an act of self-defense. Speech becomes, as John McWhorter describes it, “utterly athletic,” and capable purely by itself of bounding about, inflicting harms on virtuous-but-fragile college undergraduates.

“Safety-ism.” It has become common to ridicule these harms as a fiction, as a form of juvenile retrogression in which college students are encouraged to behave like three-year-olds who have been told unpleasant truths about what they must eat for dinner. This would be a mistake, because standing behind the cultivation of fragility and “safety-ism” in speech has a long political rationale, stretching back to the premier Marxist philosophers of the last century—Antonio Gramsci, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer, and, in America, Herbert Marcuse.

From Gramsci to Marcuse and beyond, they have sought to transfer Marx’s concepts of bourgeois domination of the working class from being the brutal business of political oppression to the more subtle imposition of cultural hegemony. The policeman’s truncheon, in other words, has been exchanged for soothing political words about freedom and liberty, but the result is always the same.

In that fashion, in Marcuse’s memorable phrase, free speech is actually “repressive tolerance,” creating an apparently free political order, whose freedom is in practice a disguise for ensuring control. Speech is literally action. And free speech should not be mistaken for some objective attempt to allow reasonable people to arrive at truth. There is no truth, only power; and free speech is only an anesthetic to numb the grinding of that power.

Hence, the use of heckler’s vetoes, accusations of bizarre or even imaginary bigotries, and outright physical force are rationalized by the conviction that the only quantity operating in a political system is power, and that such suppression of speech is a perfectly permissible way of countering one form of power with another that protects the “disfranchised” or “marginalized.”

It may come as some slight consolation to the speech suppressors to know that this defense of speech suppression is not new in American life. What will diminish that consolation is the discovery that this was the language and the tactic of Southern slaveholders before the Civil War.

A History of U.S. Speech Suppression. Slaveholders also believed that speech and actions flowed together, and that the public utterance of abolitionist speech would render their slaves ungovernable and threatening. Hence, states that legalized slavery not only banned the circulation of speech that advocated the emancipation of slaves, but censored the United States mail, attempted to prosecute northern abolitionists under a tissue-thin doctrine of “constructive flight,” and finally induced the United States House of Representatives to refuse the discussion of petitions criticizing slavery (thus cancelling another First Amendment right).

In an uncanny echo of campus administrators’ pleas that certain speakers would cost them too much in security costs to allow them to speak freely, Boston’s aldermen closed Faneuil Hall in 1837 to an abolition meeting on the grounds that such a meeting would cause a breach of the peace.

Of course, what is also worth noticing is that opponents of slavery in the 1830s argued back with what are surprisingly modern legal responses: that the First Amendment’s guarantees are national and not limited to the binding of Congress and that the location of sovereignty in a republic in the body of the people at-large means that the arbitrary suppression of speech by some agency, whether public or private, is an assault on the fundamental order of a republic. I do not know that these arguments have any less force now than they did then, when they cost some abolitionists their lives.

The Soul of the University. The other troublesome aspect of the current rash of speech suppression is its location on university and college campuses, for the suppression of speech has been a violation of the soul of the university for as long as there have been universities, and indeed as far beyond that as Socrates.

Universities are, as Keith Whittington has written, the incubators of ideas, something that is especially important for universities in a democratic society. Monarchies and despotisms only want universities for the credentialing of their servants. But in a democracy, where the search for understanding never arrives at a single point, free speech is essential to the advancement of knowledge and understanding. Within the life of the university, there is only one criterion for determining who may speak, and that is expertise.

Granted, that expertise is not always easy to determine. What is, however, easy to determine is that substituting comfort for dissent and social engagement for intellectual curiosity are poisons to the life of the university. Not only do they [modern universities] encourage obstruction and ostracism, they stifle all attempts at the improvement of understanding as posing too great a risk—and they thus ensure what Whittington calls “a failure of the university to fully realize its own ideals and aspirations.”

It is unclear whether President Trump’s executive order will have any effect on this. In fact, one of the earliest responses to Trump’s order came from former New York University President John Sexton (whom Time magazine hailed in 2009 as one of the 10 best college presidents in the country), who dismissed the problem of censorship on American university campuses as “fictitious.”

This see-no-evil approach is startling, considering what everyone else has had no trouble seeing. But for those who can see, the question then becomes, what can be done?

Addressing Campus Speech Suppression. There are certainly several ways that university leaders, trustees, students and alumni can speak to the suppression of campus speech.

First, rebuke the attitude, which reduces college students to children who require vast doses of protectiveness.

Second, expose the use of obstruction and disruption for what they are—the tactics of despotism.

Third, seek alliances with all those who, irrespective of their political identity or allegiance, are troubled themselves by the suppression of free speech.

Fourth, agitate, agitate, agitate for viewpoint diversity. Not just diversity as diversity, but viewpoint diversity and administrative neutrality.

Only then can the cloud of unreason begin to dissipate, as surely it must when confronted by wisdom and the search after truth.

Allen C. Guelzo is Director of Civil War Era Studies and Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College

II. Fixing the Federal Courts and Taming the Administrative State

The Myth of Substantive Due Process: Why Both Progressives and Conservatives Are Wrong

Randy Barnett

I want to thank the Bradley Foundation for inviting me to participate in this program.

For purposes of these remarks, I am going to assume that originalism is the appropriate method of constitutional interpretation. I can sum up “originalism” in a single-sentence sound bite: Originalism is the proposition that “the meaning of the Constitution should remain the same until it’s properly changed—by amendment.” That’s all originalism is.

Why Originalism? But why is originalism the proper method of constitutional interpretation? I can summarize one argument for originalism in four sentences: “This Constitution is not the law that governs us. It is the law that governs those who govern us. They in turn make laws to govern us. And those who are to be governed by this law can no more properly change it without going through the amendment process than we can change the laws that govern us without going through the legislative process.”

But here is one more relevant fact to why originalism is justified: We the People are never asked for our consent to the Constitution. At best, the Constitution is supported by tacit consent. But each and every person who receives power under this Constitution takes a solemn personal oath to be bound by its terms. That oath would be an oath to nothing if the terms of the Constitution can be revised or selectively ignored by those who pledge to be bound by it.

The good news today is that, as a result of the election of 2016, a new generation of judges are taking the bench who have some grasp of, and agreement with, these basic principles. Frankly, the election of 2016 was a Flight 93 Election—to coin a phrase—for the Constitution. For if Hillary Clinton had won, and we had eight more years of democratic appointments to the federal judiciary, it would have meant the end of the original meaning of our Constitution, in my view, for all time.

Had that happened—and like many in this room, I fully expected that it would—my plan was to leave the subject of constitutional law behind me and return to contract law, which was my previous area of expertise. I would have abandoned the study of constitutional law because it would have been “game over” for the Constitution we believe in—not just for my generation, but for all generations to come.

So in 2016—thanks to Donald Trump’s commitment to nominate originalist judges and the truly remarkable fact that he kept that promise—we dodged an existential challenge to the Constitution. We are now playing with a bonus ball or with the house’s money. Pick your metaphor.

What then are the challenges now facing us in this new and, frankly, unexpected judicial environment? I suppose there are many, but I will focus on just two. The first is intellectual, and the second is political.

Stare Decisis. The first is the doctrine of stare decisis or precedent. This is the view that judges should follow the previous decision of their courts—and, in particular, of the Supreme Court—even when those decisions are wrong as a matter of original meaning. In other words, even though a decision of the Supreme Court is in conflict with the original meaning of the Constitution, a good judge will follow the previous decision nonetheless.

The challenge this doctrine poses to our Constitution is obvious. If current justices must follow previous decisions rather than the original meaning of the constitutional text, it elevates the decisions of justices—including long-dead justices—over that of the fundamental law to which all justices and judges take their oath. Because the Supreme Court has been adopting doctrines in conflict with the express provisions of the Constitution since before I was born, the doctrine of stare decisis seems to entail that our movement away from the original Constitution is locked in, and its original meaning can never be restored.

At their confirmation hearings, all of our originalist judicial nominees have pledged to adhere to stare decisis, and it makes sense that they would. To assert the original meaning of the text would, for example, seem to warrant undoing much of the current administrative state. Such a stance could be painted as radical and dangerous. Each nominee would be put on the defensive to defend every claimed originalist result that might be unpopular—a daunting task indeed. Far easier and safer it is simply to pledge to follow existing precedents. So they all do.

It is not as though stare decisis has no role to play in judicial decision-making. It is unreasonable to expect each individual justice or judge to decide every constitutional question that arises de novo. It makes sense to defer to previous decisions unless and until one is persuaded that these decisions are in conflict with the higher law provided by the Constitution.

We do want lower court judges—what the Constitution refers to as “inferior” court judges—to follow the rulings of the Supreme Court rather than strike out in their own directions. Case in point: for the past 10 years, lower federal courts have been resisting following the Supreme Court’s rulings in D.C. v. HellerREF and McDonald v. City of Chicago,REF protecting the individual’s right to keep and bear arms.

There is a reasonable argument to be made that when a previous court has made a good faith effort to identify and implement the original meaning of the Constitution, these previous rulings are entitled to respect unless shown to be demonstrably in error. But this argument does not extend to previous decisions that did not purport to follow original meaning. Such decisions are not entitled to the same respect.

I do not have time now to explore possible answers to the challenge to the original meaning of the Constitution posed by the doctrine of stare decisis. Indeed, I plan to make this the subject of my summer research. But I can tell you from personal conversations that our new justices and judges are hungering for an answer to this challenge. I believe there are answers to be found that do not entail the wholesale overturning of existing institutions overnight.

For example, previous decisions can be limited to their holdings—and simply not extended to future programs. And their logic need not be extended to situations that were not previously before the Court. Such was the situation with the individual insurance mandate we challenged in our lawsuit against Obamacare. Because such a purchase mandate was literally unprecedented, no previous Supreme Court decision could possibly have authorized it. And the logic of previous decisions should not be extended to this novel exercise of government power. Happily, we actually got five votes for this proposition. We lost the case when Chief Justice Roberts adopted a “saving” construction that construed what the statute referred to as a “requirement” to buy insurance enforced by a “penalty”—instead as an option to buy insurance or pay a modest and noncoercive tax.

Democrat Court-Packing. Which brings me to the second and last challenge to the Constitution that I will discuss. Whereas the proper stance an originalist judge should take towards stare decisis is, in large measure, intellectual, this second challenge is political: It is the challenge posed by the extensive talk of court packing by Democrats—including many of the Democratic candidates for President. By “court packing” we mean expanding the number of Supreme Court justices to defeat the current conservative majority.

To be sure, such an expansion is not itself unconstitutional. The Constitution does not stipulate the number of justices. That number is set by Congress. In our history, Congress has set the number to be as few as six and as many as 10. But we have had a “norm” of nine justices for roughly 150 years.

If implemented, court packing would reverse the victory for the Constitution represented by the 2016 election. It would all but end the Supreme Court as an institution that provides a check on the unconstitutional expansion of federal power.

But court packing can only happen if and when the Democrats control both houses of Congress, and the presidency—and they abolish the legislative filibuster in the Senate, as I think they would. Moreover, as happened when Franklin Roosevelt proposed his court-packing scheme, it is not at all clear that enough Democrats would be on board the court-packing train to let it reach that destination.

No, the real challenge to the Constitution posed by these court-packing proposals is not that they actually get implemented. I believe court packing is now being proposed as a means to intimidate the existing conservative Supreme Court majority. In particular, it is a threat aimed at Chief Justice John Roberts.

Democrats already know that threats of these sorts work. As reporting has shown, Chief Justice Roberts changed his vote on the individual insurance mandate after the justices’ initial conference. It is reasonable to conclude that he was affected by the outpouring of rage aimed at the conservative justices in general, and at him in particular, after what seemed like our success at oral argument in the case.

Once you have shown you can be intimidated or rolled, it only encourages people to try to intimidate and roll you again. While I think it is very unlikely for court-packing to actually be adopted, my experience as a lawyer challenging Obamacare makes me much less optimistic that it will not have its intended effect on the Chief Justice.

One solution to this prospect is to add an additional constitutional conservative justice to the Court. One lesson of the Obamacare challenge is that five constitutional conservatives are not enough. All it takes is one to break under pressure. But this is a solution that is outside our power to effectuate. Only fate will decide whether President Trump ever gets the opportunity to add a sixth justice to the Court. Should he get that chance, to get another constitutional conservative on the bench would require that Republicans still control the Senate.

Barring the addition of another justice, the only way to meet the immediate threat that court-packing proposals pose to the current conservative majority is to take these proposals very seriously—and to appreciate the goal at which they are aimed. We must do everything we can to defeat them in the court of public opinion and, ultimately, at the polls.

One reason to be optimistic that this can be achieved is the miracle of the 2016 election, when we were staring down into a constitutional abyss, but survived not only to fight another day but to advance the ball farther than at any time in my lifetime.

Thanks in no small part to the efforts of those in this room, and those of the Bradley Foundation, we are continuing to build an intellectual infrastructure to meet these and other challenges to Our Republican Constitution–which is the title of my most recent book. And perhaps even to “Restore the Lost Constitution” that was given to us by the Founders as well as by the Republicans who enacted the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments—the provisions that kept the promise originally made by the Declaration of Independence.

Randy Barnett is Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Legal Theory and Director of Georgetown Center for the Constitution at Georgetown University Law Center.

Stare Decisis and the Court: A Litigator’s Perspective

Paul D. Clement

It’s always a pleasure for me to be at a Bradley Foundation event, because the Foundation, like me, hails from southeastern Wisconsin.

I’m going to talk about stare decisis from a lawyer’s perspective, and the reason that “lawyer’s perspective” is in the title of my remarks is to excuse me from the need to have a grand theory of stare decisis or what the proper role of stare decisis really ought to be.

Instead, I’m going to talk about stare decisis from the perspective of a litigator, which in the Supreme Court means trying to get to five votes for your client. With that caveat in mind, I want to start by talking about the current Supreme Court.

One of the oldest adages in Washington D.C. is that if you change one member of the Supreme Court, you really get a whole new court.

I think that’s generally true. People who do not watch the court as closely as Supreme Court litigators sometimes fail to appreciate how much the interpersonal dynamics of the justices make a huge difference as to how they decide cases and how they interact. It’s easy to look at the job description of the Supreme Court Justice and think, “Wow, that’s a really great job, in part, because you have life tenure.” But if you think about it in terms of basically being stuck with eight other people you didn’t pick for the rest of your life, it can be a fine line between life tenure and a life sentence.

I do think even in a normal switch, where the switch doesn’t really affect the obvious balance of power on the Supreme Court or the ideological makeup of the Supreme Court, the adage is true. Just changing a single justice really can change the dynamic of the court in pretty important ways.

I think in this particular, most recent addition of a new justice, though, you really have this adage taking on particularly powerful meaning for two related reasons.

The Kavanaugh Confirmation. One is the nature of the confirmation hearings. I think that the other eight justices might have had slightly different perspectives on who was most to blame and why the process got to where it has gotten. But I think all of the other eight justices looking at this process could agree that the process does not reflect well on the court as an institution. I think the fact that the confirmation hearings had the characteristics that they did has had an impact on the way the court is trying to operate and the way justices are interacting with each other.

Personnel Changes. The second thing, and this is perhaps the most obvious point, is that we’ve gotten used to a series of changes of personnel on the Supreme Court in recent years that haven’t really changed where the court is on important issues. The recent pattern has contrasted with some of the nominations in the past [in which] Presidents ended up with justices who behaved very differently from what the President had in mind when he made the nomination.

One of the most interesting things about the last four or five nominations before Justice Kavanaugh is that the Presidents have pretty much gotten the justice they were looking for. The court’s overall trajectory hasn’t changed that much because you basically had more or less like-for-like switches. Among the recent appointments before Justice Kavanaugh, the most consequential change was Justice Alito for Justice O’Connor. But the other ones really were almost pure like-for-like switches.

The fact that Justice Kavanaugh is replacing Justice Kennedy certainly does have the potential for bringing a more dramatic change in the trajectory of the court. I think court watchers, probably going back 40 or 50 years, have grown accustomed to trying to identify who is the Supreme Court’s swing justice. For the last decade, that’s pretty obviously been Justice Kennedy, and I think before that it was pretty obviously Justice O’Connor, and one could go back even further.

I think the search for the swing justice on the current court may come up empty. I’m not sure there is one. That isn’t to say that I don’t think there’s the fifth justice whose vote is most likely to be the one that a lawyer has to be most focused on in trying to get to five, but I don’t think it’s right to think of that justice as a swing justice. The Justice I have in mind is perhaps not surprisingly the Chief Justice.

Swing Vote? I don’t think it’s really right to think about Chief Justice Roberts as a swing justice in the sense of his vote really being up for grabs or even how he is going to think about a legal issue swinging from one side to the other. I think the right way to think about the Chief Justice is less as a swing justice and more as a governor switch or a regulator who will be the justice that determines how quickly the court moves in one direction or another, and how quickly—and how boldly—the court is willing to revisit certain areas of the law. Or instead, stay a course that at least five justices would think of as the wrong course if they were considering the matter on a clean slate.

But the Chief Justice, in particular, may be concerned about overturning past precedent of the Supreme Court. That’s why I think that the issue of stare decisis is so important from a litigator’s perspective and thinking about what the Supreme Court is going to look like in the years going forward.

The Confirmation Process and Upcoming Cases. I’d make a couple of points about this. First, part of the reason that stare decisis is important and controversial gets back to the confirmation process. Every one of the justices who goes through that process gets asked over and over again about stare decisis and precedent and super-duper precedent and all the rest. I think there’s a natural reluctance once you’ve gone through that process to immediately switch gears and instantly adopt Justice Thomas’s view of stare decisis, which is essentially if a decision is wrong, we should overrule it.

Second, the importance of stare decisis is obvious from just looking at the cases before the Supreme Court this term. By my count, there are at least four cases where the Supreme Court has directly in front of it the question of whether to overrule one of its precedents, and that really understates the number of cases where stare decisis principles are implicated.

But there are four cases where the question presented is literally: Should the court overrule its precedent in fill-in-the-blank? The four cases are the Knick case involving a Takings Clause issue that’s being ably litigated by the Pacific Legal Foundation; the Hyatt case involving state sovereign immunity; a case about the separate sovereigns exception to the double jeopardy clause; and a case involving administrative law and whether or not to overrule the so-called Auer doctrine or Seminole Rock doctrine.

One interesting thing that all four of those cases have in common is that the Supreme Court hasn’t decided them yet—even though it’s relatively late in the term and some of these cases were argued relatively early in the term. Most intriguingly, of course, is the Knick case, which was argued at the very beginning of the term, even before Justice Kavanaugh was confirmed, and then had to be reargued later in the term presumably because the other eight justices were evenly split about what to do with their prior precedent in Williamson County.

The role of stare decisis will be an important theme for this term of the Supreme Court. This term isn’t the most interesting as measured by headline-grabbing, blockbuster cases. There’s actually something to be said for that. But I think in watching the decisions of the court this term and what they say about the future of the court, there may be very little you can do that’s more effective than paying attention to these four cases where stare decisis is front and center and see how the court decides those cases and how the justices divide.

I’ll go out on a limb here and say I’m quite sure they’re not going to overrule all four precedents. I’d be surprised if they didn’t overrule at least one of them. I think which ones they decide to overrule, why that one and not others, and what the various justices say about that will provide profoundly important clues about the trajectory of the court going forward.

As I said, I think four really understates the matter, because there’s a fifth case, which is the partisan gerrymandering case, where I suppose you could say part of the question is whether the court should overrule Davis v. Bandemer?REF This is the one case that I was directly involved with, and we did not put the question of overruling Bandemer front and center, and that’s a segue to the final things I want to say about stare decisis from a litigator’s perspective. If you’re trying to litigate a case where there is a precedent of the Supreme Court that you think is wrongly decided and is in the way of your client getting to the victory circle, how do you deal with that fact?

Litigators and Stare Decisis. I’d offer three observations that seem to me to be good advice for litigators in dealing with stare decisis issues in the current Roberts Court. The first is, as a general matter, I would think about asking the court to overrule one of its cases in terms of “break glass in case of emergency.” You shouldn’t be afraid to do it—there are emergencies, after all—but it should not be your litigation strategy of first resort.

I have written a long brief that didn’t mention the idea of overruling one of the court’s cases until about the last three pages. The court actually did overrule its precedent in that case. But it just goes to show that you ought to give the court lots and lots of reasons to think that you’re right before you then say, “Oh, and this previous turn that you took in the opposite direction was not just wrong, but so manifestly wrong that you should overturn it.”

The second piece of advice follows directly from that page allocation I mentioned. When you ask the court to overturn its precedent, there’s no particular need to dwell on the matter or wrap yourself around the axle in arguing the various factors that the court from time to time has articulated as being the basis for when it will overturn its decisions. I certainly think it’s important to nod in the direction of those factors and to cite your favorite stare decisis case. Payne v. TennesseeREF is one that nicely articulates the factors, and the court did in fact overturn one of its precedents in Payne.

You certainly have to understand and address considerations like reliance, interest, and the workability of the test in practice. But I think it’s a mistake to think that the court is so consistent about how it thinks about stare decisis factors that the way to really win one of these cases is to convince them that three out of four stare decisis factors articulated in some case all cut in your favor. I think you can do essentially all you need to do in about three pages at the end of your brief.

The last piece of advice I would offer—and I think this is particularly true in the current court and particularly true with Chief Justice Roberts—is to keep in mind that asking the court to revisit a precedent may require a long-term perspective. Don’t think that the court will necessarily overturn a precedent the first time it considers the possibility.

I think one of the things that is emerging as a discernible methodology of Chief Justice Roberts when it comes to matters of stare decisis is that it is often a multiple-step process. His preferred methodology seems to be to essentially chip away at cases in various steps so that the day that the case is actually overruled, it’s really not even news. It has been coming for a couple of years and the precedent’s imminent demise was predicted so early and often that it’s just not a big deal when it finally happens. For example, when the Court overturned Austin in Citizens United, it signaled that was coming by ordering reargument in the case to focus specifically on that question.

You saw this in the last couple of terms with Abood in the public sector union context. The court chipped away at that precedent. The court had a prior case out of Illinois where it all but overruled Abood. Then, because of the timing of Justice Scalia’s passing, they had another argument to expressly overrule Abood, and then that case was dismissed, essentially putting the issue on hold for a couple of years. My goodness, by the time they finally overruled Abood last term, it was the oldest news in town.

Thus, I do think that with respect to stare decisis in the current court, it pays to take the long view.

Paul D. Clement is Partner at Kirkland & Ellis, LLP, in Chicago, Illinois.

Judicial Fortitude: Reining in the Administrative State

Peter J. Wallison

I’m honored to be able to participate in a Bradley Symposium, and I’m glad to see that there are so many people here to listen to a speech about something as important and interesting as administrative law.

The title of my talk today is the title of the book I’m going to talk about, Judicial Fortitude: The Last Chance to Rein in the Administrative State. The reason I think that conservatives should be concerned about the growth of the administrative state is not simply our respect for the Constitution.

The vital fact is that the administrative state is a direct threat to the representative democracy in this country and should be viewed in that light.

If the drift toward lawmaking by administrative agencies continues as it has since the New Deal, at some point in the future, the American people are going to realize that the rules they have to live under are being made by an unelected bureaucracy in Washington—and not by the Congress that they vote for every couple of years.

Brexit and State Legitimacy. Unfortunately, we know what happens then. We have a recent example in Brexit, where the British people voted to leave the European Union in large part because they were subject to regulations coming out of Brussels over which they had no control. Brexit was simply a statement that a majority of the British people no longer consider the EU to be a legitimate government.

In the same way, and for the same reasons, as I wrote in Judicial Fortitude, the American people’s recognition that their government is, in fact, beyond their control will create a threat to the legitimacy of the U.S. government. Without legitimacy, governments do not have the moral authority to demand obedience to the laws.

For the sake of the U.S. government’s legitimacy in the future, it is important that we find a way to control the inexorable growth in the power and reach of the administrative state.

Legislative Deniability. The underlying reason that agencies of the administrative state have grown to their current state of dominance—as suggested in this morning’s panel—is that Congress has stopped performing its constitutional role as the nation’s legislature. Legislators are supposed to make the major choices for society—who is benefited, who is burdened, who pays the cost—but Congress has found that it can get credit from the voters if it passes laws that are essentially nothing more than goal setting.

Congress passes the Clean Water Act, and simply sets a goal of clean water. When a constituent complains that his use of his farm pond is now subject to regulation by the EPA, his representative or senator says, “I didn’t vote for that; it was that out-of-control EPA again.”

The constituent doesn’t realize that Congress gave the EPA the power to make these key decisions about the scope of the Clean Water Act instead of making those difficult decisions itself. In other words, since the New Deal, and—increasingly today—the administrative state has grown larger and more powerful because Congress has handed over to these agencies larger and larger portions of its own legislative authority.

Chevron. Sadly, the courts have assisted in this process, especially the Supreme Court’s 1984 ChevronREF decision. That ruling directed lower courts to defer to agency views about their own authority if the agency has taken steps that the court thinks are reasonable in terms of the powers that the agency has been given by Congress. This gave agencies enormous latitude to expand their reach, including by adopting expansive interpretations of statutes that were already on the books.

As a result, in the last 25 years, the agencies of the administrative state have issued more than 3,000 rules in every year, for a total of over 101,000 rules in 25 years.

The Framers created a Constitution with separated powers for a specific reason. Their view was that if the power to make laws and the power to enforce laws were held by the same person or group, that was the source of tyranny.

That’s why all lawmaking power was vested in Congress, which was, of course, a representative body that was to be completely separated from the enforcement power of the executive branch.

However, the broad powers that Congress has been giving to the agencies of the administrative state are a clear violation of the constitutional structure. The power to both make the laws and to enforce the laws is now very often held by the same group of people—that is, the agencies of the administrative state.

This is not only a violation of the Framers’ intent, but as I noted earlier, it will inevitably lead to the government’s loss of legitimacy.

How can we right this ship? I believe the current Supreme Court, with its majority of conservatives and constitutionalists, is the answer. Not only do these justices respect the Constitution and the need for the separation of powers, but the Supreme Court has a duty—a duty given to them by the Framers—to correct violations of the constitutional structure.

A Jurisprudence of Non-Delegation. In Federalist 78, Alexander Hamilton said that the judiciary was intended to be the “guardian of the Constitution.”REF Judges were given lifetime appointments so they could stand up to the more powerful elected branches when the elected branches were engaged in actions that would change the way the Constitution was supposed to operate. Judges were given life tenure, said Hamilton, because this was necessary to give the judges and justices the “fortitude” for this difficult task.

But in almost 250 years since the Constitution was ratified, the Supreme Court has never developed a way to determine whether Congress has delegated legislative authority to the executive branch—in other words, the Court has never developed what I would call a “jurisprudence of non-delegation.”

That is the way that the Court has always dealt with general terms in the Constitution. For example, what does the Constitution mean when it says that people should be free from “unreasonable search and seizure?” We didn’t really know what that meant until the Court started dealing with the facts of actual cases, so that by this time even a foot patrolman can be told by his commanders what he can do—or can’t do—when he stops a car. That was a result of the jurisprudence on that issue, the facts of case after case being reviewed by the Court.

That has never been done by the Supreme Court on the question of Congress delegating legislative authority to the executive branch. Every time this question has been presented to the Court since the 1930s, the Court has approved the delegation. This has led many scholars to conclude that the non-delegation doctrine that I’m talking about here—with which the Court could invalidate unconstitutional delegations of legislative authority—has been abandoned by the Court.

Reining in the Administrative State. The only time that the Supreme Court tried to carry out its constitutional duty was in 1935, when it invalidated two laws that it believed had delegated legislative power to the President. But after Franklin Roosevelt won a smashing victory in the 1936 election, he retaliated against the Court with a plan to appoint seven new justices and, thereby, take control of the Court.

This court-packing plan, as it is known, was unpopular with the public, and it was never passed by Congress. But it appeared to cow the Court, which has never again declared a law unconstitutional because it delegated excessive legislative authority to the executive. Instead, the Court has continued to allow Congress to give broad powers to executive agencies—powers, for example, to regulate in “the public interest” or impose rules that are “fair and reasonable.” These decisions, what is included in “public interest” or what is “fair and reasonable,” are decisions for a legislature, not for unelected bureaucrats.

Yet, the only way that we will ever be able to regain control over the administrative state is through the willingness of the Supreme Court to decide that Congress has delegated its legislative power to one or more of these agencies.

We cannot expect Congress on its own to rein in the administrative state; it will not give up its ability to avoid difficult decisions by handing these decisions to administrative agencies. But if the Supreme Court assumes the role that the Framers assigned to them, as “the guardian of the Constitution,” it can force Congress to do its job.

How? By restoring the non-delegation doctrine and invalidating laws that unconstitutionally delegate legislative authority to the executive branch. With several such invalidating decisions, Congress will realize that it must make the difficult legislative decisions that it has been avoiding all along.

The Court is now well aware of this authority and responsibility. In a 2013 case, City of Arlington v FCC, Chief Justice Roberts, in dissent, cast doubt on Chevron. He also said this: “The obligation of the judiciary is not only to confine itself to its proper role, but to ensure that the other branches do so as well.”REF

This is a restatement of Hamilton’s position in Federalist 78, that the Court has a duty to stand up to the elected branches when they threaten the structure of the Constitution. It is the key to the use of the non-delegation doctrine.

I know that many conservatives, because of his votes in the Obamacare cases, question Roberts’ steadfastness as a conservative.

But in fact, that quote from City of Arlington shows that on questions of the structure of the Constitution, he’s right on target, and he has put himself in a position where he can make a major decision on the non-delegation doctrine.

In my judgment, this is where the Court is going in the future when an appropriate case, raising the non-delegation issue, arrives at the Court. By adopting Hamilton’s position that the Court has a duty to stand up to the elected branches when they threaten the structure of the Constitution, Chief Justice Roberts has made it clear that he will lead the Court in restoring the non-delegation doctrine—and thus a more effective separation of powers. This will begin the process of reining in the power of the administrative state.

In other words, it’s time for judicial fortitude.

Peter J. Wallison is Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., and author of Judicial Fortitude: The Last Chance to Rein in the Administrative State (Encounter Books, 2018).

III. The Problem of Illegal Immigration

A Question of Sovereignty

Michael Anton

I first want to say how much I appreciate some of the apocalypticism of the early speakers. I’m very used to going to gatherings like this, and everybody says, “Well we may have one or two problems, but really it’s all going to be fine. Don’t worry.” And I see a looming cliff, and I think, “I’m either crazy—or these people are.” So I like that; it’s a fresh dose of realism, a little splash in the face that helps wake one up and keep one spry.

Regarding being run out of town on a rail, I’m reminded of a famous comment of Lincoln’s, I forgot of whom he said it, but some controversy erupted, and Lincoln said, “I’m reminded of the man who was tarred, feathered and ridden out of town on a rail who said, ‘Were it not for the honor of the thing, I would rather walk.’”

So my topic is unilateral disarmament. Now you think, “Well, what does this have to do with nuclear weapons; that’s not why we invited you here?” No, it is not why you invited me here, and I do like, when anyone invites me somewhere, to play my assigned role. For instance, I was invited to a college a little while ago, and I wrote a somewhat provocative talk. But when I got up there, I kind of chickened out. I was looking out at them, and I remembered that the professor who invited me said, “This is a really liberal place, you know.” I said, “Yeah, I get it.” And I toned it down in the speech, and then afterward we all went out to dinner and he said, “You know, you kind of let me down a bit.” And I said, “How? I’m sorry, but what did I do?” He said, “You weren’t very provocative at all. You know, the students weren’t even really mad at you.” So all right, I guess I failed to play my assigned role in that case.

Unilateral Disarmament. So, unilateral disarmament. What do I mean by that? I mean the conservative intellectual movement, I think, has unilaterally disarmed itself in the immigration debate. Why have they done that? Because they accept premise after premise after premise, all of them false, from the Left that say, “If we believe in the American idea, if we believe in the Constitution and the Declaration and so on, we can’t be for any limits. We just can’t.” So they’re getting consistently beaten in this debate in ways that the first panel showed in all kinds of practical detail. I think those practical defeats stem from the intellectual and principled unilateral disarmament that I talked about.

America as an Idea? There are a couple phrases that I think conservatives would do well to retire. One of them is, “America is an idea, not a country.” Really? I have to cross the border every once in a while. I do get stopped; my passport is checked. I look at maps, there are lines; that one says there’s a country on this side of it, and there’s a country on that side of it, and neither one of them is the United States of America.

So, where does this come from? It comes from language in the Declaration of Independence and from the Founders. Now, why did they state things the way they stated it that leads our intellectuals falsely to believe that America is only an idea? Not saying that there is no American idea: I’m saying that this oversimplification, that America is only an idea, is a big source of rot that we have in the conservative intellectual movement.

Where does it come from? It comes from our Founders finding themselves in a difficult and unprecedented political situation in which they had to grope for and articulate a new basis for political legitimacy. In fact, the very opening of the Federalist Papers, Federalist 1, remarks on this unprecedented situation, and says that it has been left to us to decide whether governments are always going to be established by “accident and force” or “reflection and choice.”REF

In other words, they’re saying, we’re going to have to—essentially for the first time in human history—get together, talk about how we’re going to establish this government, and on what basis. In the full light of day. Yes, I’m leaving out the fact that the Constitutional Convention was secret, but you notice that all their notes were subsequently published, as was the document. In full light of the world, everyone’s going to see what we did and why we did it, and they’re going to interpret our reasons.

Now, the basis of political legitimacy, prior to this, had never been that. You ask yourself, why is France, France? Why is England, England, or any other country you could name? Historians can write 1000-page books on this and never get to the answer. We sort of know, first there were the Gauls, and then they were conquered by the Romans, and then there were the Franks, and so on. There’s a long, complex history, and somehow France is France at some point, but nobody can point to (unless you want to count Bastille Day), but there’s certainly 1000 years of France before that, or longer. Nobody can point to a 1776 or 1787 moment, when a people say, we are this people, defined in this way, and the people out there are not this people. You don’t have that; it’s implied somehow, and the origins of it are murky. But we have that in the United States.

Notice though, that in stating the universal truths that the Founders used to justify their act of rebellion and their act of founding a new country, they say these truths are universal. They never say, however, that this universal truth obviates or in some way makes impossible a border. In fact, everybody remembers the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” and so on.