Colonel Richard J. Dunn, III, U.S. Army (ret.)

Throughout our history, the Reserve and National Guard components of the U.S. military have made essential contributions to the nation’s defense. The Reserve and Guard make up roughly 38 percent of total U.S. uniformed manpower, and their organizations provide critical combat power and support. Though traditionally supporting combat operations in a strategic reserve capacity, more recently, they have supported undersized Active component forces in long-term engagements such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Militia service is as old as the United States. Before independence, local communities formed their own security forces, composed of citizens who would rally in times of emergency, to protect their towns from external threats. After independence, the individual states remained in the habit of raising forces—militias—as needed, providing units to complement those of the federal forces as was the case during the U.S. Civil War.

The relationships between the National Guard, the full-time Active federal forces, and the Active component’s Reserve elements have changed over time as the needs of the country have changed. For much of its history, the U.S. maintained a small Active component that was expanded by draft or mobilized reserves during times of war. Following the Vietnam War, the shift to an all-volunteer force and the heightening of tensions with the Soviet Union led to sustainment of a large standing military that changed the relationship between Active and Reserve/Guard elements, with Active elements kept in a ready status that would enable them to respond immediately to any Soviet aggression while the Reserve and Guard elements served as a strategic reserve.

Given the critical role played by National Guard and Reserve organizations, an understanding of the statutory foundations of these components, their nature, and issues surrounding their structure, size, and employment is essential to any assessment of the ability of the U.S. armed forces to provide for the common defense in today’s complex world.

The decline in the size of the active-duty force caused by reduced budgets has sparked tension among the Active, Guard, and Reserve components over their respective missions and corresponding resources. Lacking the ability to fund the existing arrangement of Active, Reserve, and Guard forces adequately, service chiefs have had to reallocate funding, forcing reconsideration of what each component needs to have and for what purpose.

Statutory Foundations

The responsibilities of the executive and legislative branches for the National Guard and Reserve components stem from Articles I and II of the U.S. Constitution.

For the legislative branch, Article I, Section 8 states: “The Congress shall have Power…To raise and support Armies...To provide and maintain a Navy...To make rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces...To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions” and “To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress….”1 For the executive branch, Article II, Section 2, states: “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States….”2The Constitution (Article 1) also prohibits states from keeping troops or ships of war in time of peace, or engaging in war (absent invasion or imminent danger), without the consent of Congress.

Title 10 of the U.S. Code, which focuses on the armed forces, further defines the purpose of the Reserve components:

The purpose of each reserve component is to provide trained units and qualified persons available for active duty in the armed forces, in time of war or national emergency, and at such other times as the national security may require, to fill the needs of the armed forces whenever more units and persons are needed than are in the regular components.3

Title 10 also describes the policy for ordering the components to active service:

Whenever Congress determines that more units and organizations are needed for the national security than are in the regular components of the ground and air forces, the Army National Guard of the United States and the Air National Guard of the United States, or such parts of them as are needed, together with units of other reserve components necessary for a balanced force, shall be ordered to active duty and retained as long as so needed.4

These constitutional and legislative measures establish and characterize full-time, federally controlled Active forces, supporting Reserve forces, and state-maintained National Guard forces that work together to protect the country, but these components vary in governing authorities and the role they play in national security.

The Seven Reserve Components

The Department of Defense (DOD) Total Force Policy defines the components of the U.S. armed forces as:

- Active Component (AC) Military. The AC military are those full-time military men and women who serve in units that engage enemy forces, provide support in the combat theater, provide other support, or who are in special accounts (transients, students, etc.). These men and women are on call 24 hours a day and receive full-time military pay.5

- Reserve Component (RC) Military. The RC military is composed of both Reserve and Guard forces. The Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force Reserves each consist of three specific categories: Ready Reserve, Standby Reserve, and Retired Reserve.6 This essay’s focus is solely on the Ready Reserve.

Title 10 of the U.S. Code further defines the reserve components of the armed forces as the Army National Guard of the United States, Army Reserve, Navy Reserve, Marine Corps Reserve, Air National Guard of the United States, Air Force Reserve, and Coast Guard Reserve.7 Together, these Reserve and Guard components constitute 38 percent of the total uniformed force and a majority of Army forces. (See Table 2.)

Specific Roles and Responsibilities of the Reserve and National Guard Components

Reserve Components. The Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard Reserves have only federal missions and are subordinate directly to the leadership of their respective services under Title 10 of the U.S. Code (which enumerates federal U.S. armed forces law). They tend to be closely integrated with the Active components of their respective services. Some Active component organizations have individual Reserve members or Reserve units directly assigned to them.8

National Guard. National Guard elements differ from Reserve elements in substantial ways, primarily in that the Guard has both state and federal missions, reflecting its origin as state militias. Title 32 of the U.S. Code describes the relationship between the federal government and the state National Guard units recognized as elements of the Army and Air National Guards of the U.S.:

In accordance with the traditional military policy of the United States, it is essential that the strength and organization of the Army National Guard and the Air National Guard as an integral part of the first line defenses of the United States be maintained and assured at all times. Whenever Congress determines that more units and organizations are needed for the national security than are in the regular components of the ground and air forces, the Army National Guard of the United States and the Air National Guard of the United States, or such parts of them as are needed, together with such units of other reserve components as are necessary for a balanced force, shall be ordered to active Federal duty and retained as long as so needed.9

All of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, and U.S. Virgin Islands have National Guard organizations responsible, when functioning under state law in state status, to their governors or chief executives for executing state missions such as disaster response or support to civil authorities during a crisis.10 The de facto operational commander of these organizations while they are under state control is the state adjutant general (TAG), usually a major general, who is the senior military official in his or her state, territory, or district.

At the federal level, the National Guard Bureau, which is a joint activity of the Department of Defense, serves as the channel of communications between the states and the Departments of the Army and the Air Force on Guard matters. The Chief of the National Guard Bureau is a four-star general. The Chief is the principal adviser on National Guard Affairs to the DOD, Army, and Air Force leadership.11

According to the National Guard Adjutants General Association, the National Guard represents the world’s 11th largest army, fifth largest air force, and 38 percent of the total U.S. military force structure “and has over 458,000 personnel serving in 3,600 communities throughout the country.”12 While this is accurate in aggregate numbers, the Guard is in reality a collection of militia-type units, each answering separately to its respective state, district, or territorial chief executive. The Guard is not constituted as a singular service or force, although issues unique to the Guard in its structure, equipping, and role when mobilized for federal service under Title 10 of the U.S. Code are handled by the National Guard Bureau. That said, with congressional delegations from all of the states and territories paying close attention to their Army and Air National Guard organizations, the National Guard has a powerful representational presence in Washington.

The Army National Guard and Army Reserve

Army National Guard. The 354,200 members of the Army National Guard provide significant forces for national defense. These include:

- Eight division headquarters;

- Six general officer–level operational commands (including sustainment as well as air and missile defense);

- 126 operational brigades and groups, including 28 Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs) (a mix of Infantry, Armor, and Stryker BCTs);

- 48 multi-functional support brigades (including combat aviation, surveillance, and sustainment brigades);

- 48 functional support brigades and groups (including military police, engineer, and regional support); and

- Two Special Forces Groups.13

The U.S. Army has relied heavily on the Army National Guard to meet its requirements in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. Since September 11, 2001, the Army National Guard has mobilized over 500,000 soldiers for federal missions. At one point in 2005, over half of the combat brigades deployed in Iraq came from the Army National Guard.14

Army Reserve. Unlike the Army National Guard, the Army Reserve has no combat units of its own. The Army Reserve constitutes some 20 percent of the Total Army force. Its 205,000 soldiers and 12,600 civilians provide 75 percent of key support units and capabilities such as logistics, medical, engineering, military information support, and civil affairs.15 It also includes structures such as voluntary public–private partnerships that amplify the total force’s capabilities,16 as well as certain unique capabilities not found elsewhere in the military such as chemical companies able to detect biological weapons.17

The Army has relied heavily on the Army Reserve since September 11, 2001. Since then, more than 280,000 Army Reserve soldiers have been mobilized to support the active Army in global operations. The Army Reserve’s 2015 posture statement reports approximately 16,058 Army Reserve members on active duty, including nearly 2,600 in Afghanistan.18

The Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve

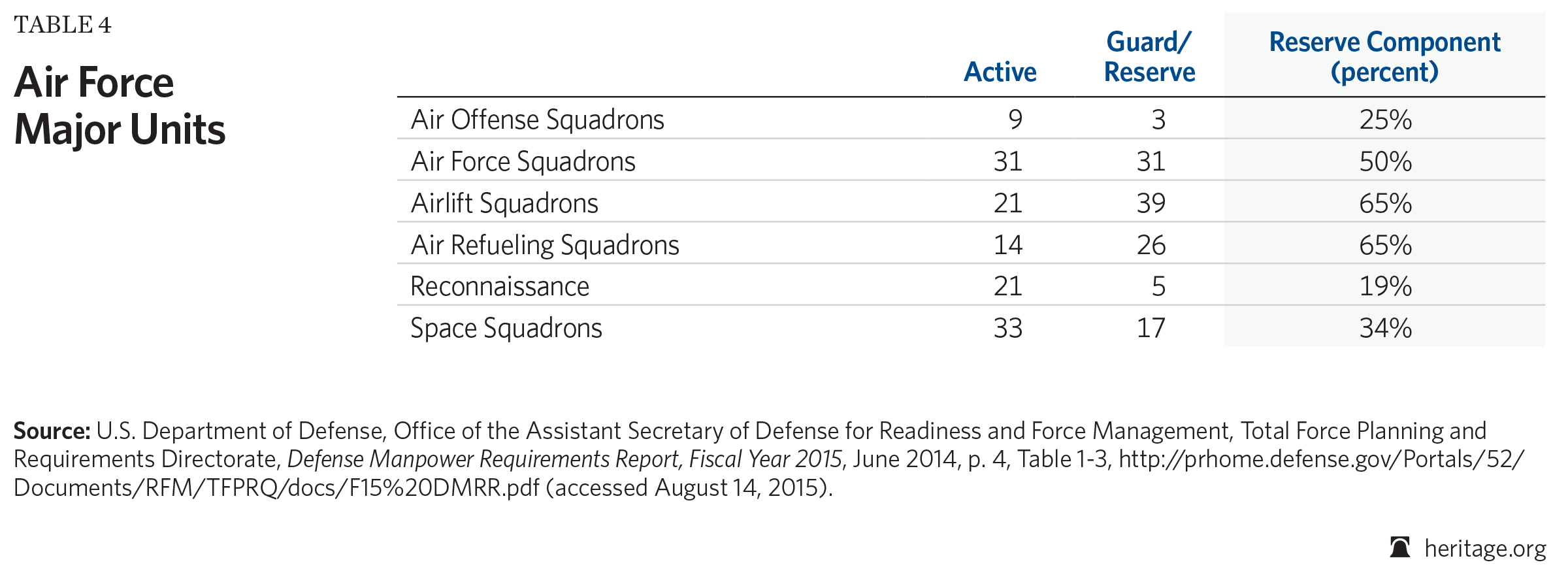

Air National Guard. The 105,400 Air National Guard members in 50 states, three territories and the District of Columbia provide 89 Wings and 188 geographically separated units. Their 1,145 aircraft constitute nearly 31 percent of the Air Force’s total strike fighter capability, 38 percent of the Air Force’s total airlift capability, and 40 percent of the Air Force’s total air refueling tanker fleet.19

Like the Army, the Air Force has depended heavily on its Air Guard component since September 11, 2001. The Air National Guard performs 30 percent of the worldwide Air Force missions each day, including the majority of continental air defense.20 Under the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), “the Continental U.S. NORAD Region (CONR) provides airspace surveillance and control and directs air sovereignty activities for the continental United States (CONUS).”21 This organization leads Operation Noble Eagle, which provides around-the-clock defense from airborne threats over U.S. territory.

The First Air Force, also known as Air Forces Northern (AFNORTH), fulfills the largest portion of this mission, of which the Air National Guard is the primary component. The First Air Force was established during the Cold War to defend U.S. territory from Soviet aerial attack. After September 11, 2001, this unit’s mission gained new purpose as airborne threats from non-state actors became a reality. According to an FY 2014 budget explanation:

The primary [Operation Noble Eagle] cost driver is the mobilization cost of National Guard and Reserve Component personnel. These mobilized personnel provide force protection to key facilities within the United States and provide an increased air defense capability to protect critical infrastructure facilities and U.S. cities from unconventional attack.22

As of January 2015, there were nine aligned Air National Guard fighter wings included in AFNORTH, flying a combination of F-15 and F-16 aircraft.23

Air Force Reserve. The 70,000 airmen of the Air Force Reserve, organized into the Air Force Reserve Command, operate the full range of Air Force aircraft and other equipment in support of all Air Force missions.24 Specifically:

[Reservists] support nuclear deterrence operations, air, space and cyberspace superiority, command and control, global integrated intelligence surveillance reconnaissance, global precision attack, special operations, rapid global mobility and personnel recovery. They also perform space operations, aircraft flight testing, aerial port operations, civil engineer, security forces, military training, communications, mobility support, transportation and services missions.25

This Reserve component flies and maintains “fighter, bomber, airlift, aerial refueling, aerial spray, personnel recovery, weather, airborne warning and control, and reconnaissance aircraft.”26 “On any given day in 2013,” according to the Chief of the Air Force Reserve, “approximately 5,000 Air Force Reservists were actively serving in support of deployments, contingency taskings, exercises and operational missions.”27

The Air Force Reserve Command is organized into three subcategories: the 4th Air Force, the 10th Air Force, and the 22nd Air Force. The majority of these forces provide a significant amount of the Active Air Force’s airlift needs, with around half of Air Force Reserve personnel involved in airlift in some way.28

The Active Air Force has relied heavily on the Air Force Reserve for combat operations. For example, during the combat phase of Operation Iraqi Freedom (March 19–May 1, 2003), “Air Force Reserve aircraft and crews flew nearly 162,000 hours and deployed 70 unit-equipped aircraft in theater while aeromedical personnel provided 45 percent of the Air Force’s aeromedical crews that performed 3,108 patient movements.”29

The Navy Reserve

The Navy Reserve has an end strength of 57,300.30 Many Navy Reservists are in the Ready Reserve, which “provides a pool of trained servicemembers who are ready to step in and serve whenever and wherever needed.”31 The Ready Reserve force is made up of the Selected Reserve (SELRES) and the Individual Ready Reserve (IRR).32

The SELRES is the largest component of the Navy Reserve and includes two subgroups:

- Drilling Reservists/Units—“Reservists who are available for recall to Active Duty status” and who “serve as the Navy’s primary source of immediate manpower.”33

- Full-Time Support—“Reservists who perform full-time Active Duty service that relates to the training and administration of the Navy Reserve program.”34 These personnel, who are full-time but do not move as frequently to different geographic locations as their active-duty counterparts do, facilitate continuity and institutional knowledge at Reserve training facilities.

The IRR “consists of individuals who have had training or have previously served in an Active Duty component or in the Selected Reserve.”35 There are two categories of IRR personnel:

- Inactive status—Reservists who have no obligation to the military and are not required to train. They subsequently receive no benefits from the military.

- Active status—Reservists who “may be eligible to receive pay or benefits for voluntarily performing specific types of Active Duty service.”36

The Navy also maintains a Standby Reserve, composed of reservists who have transferred out of the Ready Reserve but are identified as potentially able “to fill manpower needs in specific skill areas”; Retired Reserve-Inactive members, who are receiving military retirement benefits;37 and the Naval Air Forces Reserve, which includes one Logistics Support Wing, one Tactical Support Wing, and a number of helicopter and maritime patrol squadrons.38

In 2014, the Navy Reserve provided over 2 million man-days of operational support to the Navy, Marine Corps, and Joint Force, including 2,947 Reserve sailors deployed around the globe.39

The Marine Corps Reserve

The Marine Corps has a division, air wing, logistics group, and senior force headquarters—almost a quarter of its force structure—in its 39,200-member Marine Corps Forces Reserve component.40 The Marine Corps Forces Reserve is geographically dispersed throughout 47 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico.

The Marine Corps has relied heavily on its Reserve component to support combat operations since September 2001. More than 23,000 Marine Reserves—units and individual augmentees—were mobilized for Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). At the peak of mobilization in May 2003, 21,316 Reserves—52 percent of the entire Selected Marine Corps Reserves—were on active duty, primarily supporting operations in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East.41

The Marine Corps Reserve includes the 4th Marine Division, the 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, the 4th Marine Logistics Group, the Force Headquarters Group, and a Headquarters Battalion.42 The 4th Marine Division includes one assault amphibian battalion, one combat engineer battalion, one light armored reconnaissance battalion, one reconnaissance battalion, one tank battalion, three regiments, two reconnaissance companies, and one training company.43 The 4th Marine Aircraft Wing includes two Marine Aircraft Groups:

- Marine Aircraft Group 41 flies a fighter squadron (F/A-18C); a medium tiltrotor squadron (MV-22B); an aerial refueler transport squadron (KC-130T); and associated logistics and support.

- Marine Aircraft Group 49 flies one heavy helicopter squadron (CH-53E); one light attack helicopter squadron (AH-1W); one medium helicopter squadron (CH-46E); one aerial refueler squadron (KC-130T); and associated logistics and support.44

Coast Guard Reserve

The Coast Guard is a military organization with law enforcement authority, maintained within the Department of Homeland Security since 2003. While small in number, the Coast Guard is responsible for key missions such as port security—both in the U.S. and in support of overseas operations—as well as drug interdictions, aids to navigation, and search and rescue. Its “nearly 40,000” active component members are supported by (among others) roughly 7,500 members of the Coast Guard Reserve.45

The Coast Guard Reserve is similar to the Navy Reserve in that its members are assigned to Active component Coast Guard units and stand ready to reinforce them when mobilized. The Coast Guard Reserve also plays a key role in all of the maritime dimensions of homeland security.46

Historical Context

Since the Revolutionary War, the National Guard and Reserve (or their predecessors, the state militias) have provided critical support for national defense. Until the Cold War, the United States maintained a small standing regular force. Threats to national security interests were relatively small, and a large standing army was not considered necessary or even desirable. On occasions when very large ground forces were needed, such as the American Civil War and World Wars I and II, National Guard and Reserve forces provided the essential bolstering of combat power until the draft and the training establishments could provide sufficient units to the Regular forces of the Active component.

After the outbreak of the Korean War, the U.S. created relatively large Guard and Reserve forces to support the Active component in deterring Soviet Bloc aggression and defending U.S. and allied global interests during the Cold War. Unsurprisingly, this era was not without its issues related to the mission, size, readiness, cost, and equipment of the Reserve component. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara created a “firestorm” in Congress when he attempted to integrate the Guard and Reserve into the Active component.47 However, despite shortages of personnel, equipment, and funding, the Reserve component accomplished its missions reasonably well, including a massive mobilization during the 1961 Berlin Crisis.48

The Vietnam War, however, was a watershed event that shattered the relationship between the Active and Reserve components. In 1964, given the small size of the Active component following its post–Korean War drawdown and the wealth of combat experience among servicemembers in the Guard and Reserve who had served in World War II and/or Korea, the services relied heavily on the Reserve components. The U.S.-supported government of South Vietnam was rapidly collapsing under a Viet Cong onslaught supported by North Vietnam, and the U.S. moved to prepare large, regular U.S. forces for ground combat. Unsurprisingly, national-level military leaders expected to rely heavily on the Reserve component for this major combat operation.

President Lyndon Johnson, however, had other ideas.49 As noted by retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Sorley, President Johnson’s decision not to mobilize the nation for war had devastating consequences for the relations between the Active and Reserve components and for the combat effectiveness of both:

The President addressed the Nation on July 28 [1965], one of the most fateful junctures in the long war, saying that he planned to send 50,000 more troops to Vietnam…and that more would be sent as needed. Insiders waited expectantly to hear that he was authorizing mobilization to support the deployments but instead were astounded to learn that it would be done without the Reserve.

This constituted a crisis of the first magnitude for those charged with preparing and dispatching the deploying forces. The Army in particular, more reliant on its Reserves than the other services, was now in a bind. Instead of being able to supplement active units, it was now faced with replicating those forces, newly created and requiring equipment, training, and large numbers of additional young officers and noncommissioned officers.

General Harold Johnson, Army Chief of Staff from June 1964 to June 1968, recalled that the President’s refusal to call up Reserve forces constituted one of the most difficult crises in those turbulent years. The general learned of the decision in a July 24 meeting with McNamara and the service chiefs. All were stunned. “Mr. McNamara,” said Johnson, “I can assure you of one thing, and that is that without a call-up of the Reserves the quality of the Army is going to erode and we’re going to suffer very badly.”

…As a consequence, “the active force was required to undertake a massive expansion and bloody expeditionary campaign without the access to Reserve forces that every contingency plan had postulated, and the Reserve forces—to the dismay of long-time committed members—became havens for those seeking to avoid active military service in that war.”

…The effects General Johnson predicted were soon felt. In late 1966 he observed that the level of experience in the Army was steadily diminishing. … “By 1 July 1967,” he forecast from the force expansion already planned, “more than 40 percent of our officers and more than 70 percent of our enlisted men will have less than 2 years of service.”…50

The Vietnam War and its aftermath had a profound impact on U.S. senior military leadership in many ways and on the relationship between the Active and Reserve components. General Creighton Abrams, who as Vice Chief of Staff of the Army had overseen the preparation of Army forces for deployment to Vietnam and who had served as commander of all forces in that engagement, became Army Chief of Staff in 1972 and began to restore the combat effectiveness of an Army that had seen its morale crumble during the Vietnam War. To enhance readiness and expand the size of the force available for large-scale operations, he and then-Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird created the Total Army concept that integrated the Active and Reserve components much more closely.

Some have argued that one reason for this approach was to make it impossible for the Army to go to war again without the Guard and Reserve. Some also claimed that the resulting “Abrams Doctrine” would limit the ability of future Presidents and Congresses to commit the U.S. to war without first garnering the public support required to mobilize and commit the Reserve components. However, the historical record does not substantiate this claim.51

The Abrams Doctrine led the Army to integrate the components to the degree that a third of the force structure of most Army divisions stationed in the continental U.S. was made up of National Guard units. To provide the President with the necessary access to the Guard and Reserve absent a declaration of war or declared national emergency, Congress created the Presidential Reserve Callup Authority in 1976.52

The Total Army concept was tested in the response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. While over 37,000 Guard and Reserve soldiers performed combat, combat support, and combat service support missions during the conflict, three Active divisions with “Roundout Brigades” deployed without them. These brigades were activated just before offensive operations began, but due to concerns about their readiness for immediate combat employment, they were first sent to the National Training Center in California to train and be evaluated. Afterward, a GAO report found that the Guard and Reserve forces supporting the Army were not at the appropriate level of readiness.53

The next major change in the relationship between the Active and Reserve components occurred after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As the engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan turned from conventional operations needed to overthrow Saddam Hussein and the Taliban, respectively, to prolonged counterinsurgency and nation-building operations, the relatively small Active component ground forces became increasingly strained to sustain the high numbers of forces needed in the field.

Greatly downsized from its Desert Storm levels, the Army was able to expand its force structure only modestly. Restricting sustained operations to just the Active component meant that its small but highly trained force would be deployed indefinitely, likely exacting a toll on its morale and ability to retain skilled personnel. Or it could once again turn to its Reserve and National Guard elements to expand its capacity for sustained operations.

With time to train and properly prepare before deployment, Army National Guard brigades began to assume their place in a rotation schedule for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. “At one point in 2005, half of the combat brigades in Iraq were Army National Guard—a percentage of commitment as part of the overall Army effort not seen since the first years of World War II.”54 With combat rotations scheduled well in advance, Reserve component units were given the same time and training resources to prepare for deployment that Active component units received.55

Air Force operations were similarly supported by large, sustained mobilization of Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard units that handled strategic lift, aerial refueling, and surveillance duties, among others, alongside their Active component counterparts. In similar manner, the Marine Corps sustained its deployment cycles to Iraq and Afghanistan through heavy reliance on its Marine Forces Reserve units.

Major Issues Concerning the Reserve and National Guard Components

The current budgetary uncertainty surrounding all of America’s armed forces has generated several contentious issues related to the Guard and Reserve that, left unresolved, might well compromise their future effectiveness. These issues relate to the appropriate balance between the Active and Reserve components and include their respective roles and missions, size, structure, and equipment. All of these in turn weigh on the relationships between the Active and Reserve components.

Balancing Resources. The Budget Control Act of 2011 and the subsequent caps on defense spending have placed all of the armed forces under tremendous pressure as they deal with an increased demand for operational and “presence” missions in spite of shrinking forces and resources. One struggle between the Active and Reserve components is in striking the right balance in allocating resources that include funding, access to training facilities and resources, and apportionment of manpower.56

Having worked alongside Active component forces for over a decade in Iraq and Afghanistan, some in the Guard and Reserve have made the case that they can assume more missions in the future and can do so for less money than active-duty forces consume.57 The Active component has countered that given their restricted training time,58 Guard and Reserve units cannot maintain the same high readiness levels required for many critical missions, particularly concerning complex joint and combined arms operations.

Both arguments have merit. Reserve component forces are less expensive than Active component forces when not activated, because the costs of sustaining Guard and Reserve personnel (salaries, schools, housing, medical care, etc.) are borne in large part by the civilian economy. Even when activated, they are somewhat less expensive over the long term because of differentials in retirement benefits. Because they train less frequently, they also consume less fuel, ammunition, and other supplies and require less maintenance for their equipment when not activated.

It is also true that the Active component maintains a higher level of readiness. Active component units train throughout the year, honing their ability to execute both tactical actions and higher-level operations that, due to their complexity, place great demands on senior-level staffs. Guard and Reserve performance in Iraq and Afghanistan was as good as it was not only because of the dedication of the members involved, but also because they were given the time and resources required to train to the same tactical standards as Active component forces before they deployed.59

Balancing Roles. Traditionally, the Guard and Reserve components have served as a national strategic reserve force, a national asset that can be mobilized in times of significant crisis to provide expanded military capacity to the Joint Force. In the recent engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan, however, they have often served as an operational reserve, filling the manpower needs of an overly taxed Active component. “As an operational reserve,” writes Dr. Daniel Gouré of the Lexington Institute, “Guard forces participated routinely and regularly in ongoing military missions. Entire Guard brigade combat teams (BCTs) were deployed to both conflicts, [and] Guard officers commanded entire multi-national Corps in Iraq.”60

To their credit, the Guard and Reserve components filled this role well, but it has made them more closely resemble the Active component. The time required to prepare and train to deploy, and the overseas deployments themselves, have exceeded what had previously been expected of individuals not serving full-time in the Active military component.

The difficulty of achieving balance in resources and in the roles and missions assigned to Active, Guard, and Reserve elements has drawn focused attention at the highest levels of government. In 2013, Congress created a National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force to “determine whether, and how, the structure should be modified to best fulfill current and anticipated mission requirements…in a manner consistent with available resources.”61 The commission submitted its report on January 30, 2014, recommending in part that the Air Force should “entrust as many missions as possible to its Reserve Component forces”62 while realizing that “there is an irreducible minimum below which the Air Force cannot prudently cut Active Component end strength without jeopardizing warfighting capabilities, institutional health, and the ability to generate future forces.”63

In 2015, Congress also convened a National Commission on the Future of the Army to undertake a comprehensive study of the “structure of the Army and policy assumptions related to [its] size and force mixture” in order to assess “the size and force structure of the Army’s active and reserve components.”64 The commission is scheduled to submit its report to the President and Congress by February 1, 2016.65 Although initially considered as a mechanism to resolve a dispute between the Active and Reserve components over the allocation of helicopter assets, the commission was charged with taking a broader view of the role played by each element in providing essential capabilities that constitute a majority of America’s ground combat power.

A Critical Component of National Security

Our armed forces must be prepared to support an effective national military strategy across the full range of potential threats that the nation faces in the current and uncertain future threat environment. This calls for Guard and Reserve component forces to be postured for action in ways that best suit their organizational nature, their access to resources, and the demands of evolving operational and strategic requirements. In general, the Reserve component, composed of Guard and Reserve forces, best supports the country by serving as the nation’s insurance policy in the event that the Active component finds itself in major combat operations rather than by substituting for the Active component in smaller contingencies due to an undersized Active force.

The Reserve and National Guard elements of the U.S. military provide critical support to the common defense of the nation every day. Whether flying supply and logistics support missions, acting as the federal government’s first response force at home, or supporting active-duty forces during combat engagements overseas, these components have enabled and enhanced the U.S. military’s overall capabilities and capacities.

The men and women who compose the Reserve components are a testament to the desire, willingness, and ability of our countrymen to serve the security interests of our nation while also contributing to the wealth, resiliency, vitality, and stability of our nation on a daily basis in their various capacities as private citizens when not soldiering. Our Reserve and National Guard forces are national assets that must be resourced and supported in a manner that is commensurate with their critical functions in preservation of the nation’s security.

Endnotes

- House Document No. 110-50, The Constitution of the United States of America As Amended, 110th Cong., 1st Sess., July 25, 2007, pp. 4–5, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CDOC-110hdoc50/pdf/CDOC-110hdoc50.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Ibid., p 7.

- 10 U.S. Code § 10102.

- 10 U.S. Code § 10103.

- U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Readiness and Force Management, Total Force Planning and Requirements Directorate, Defense Manpower Requirements Report, Fiscal Year 2015, June 2014, p. v, http://prhome.defense.gov/Portals/52/Documents/RFM/TFPRQ/docs/F15%20DMRR.pdf (accessed August 14, 2015).

- Ibid.

- 10 U.S. Code § 10101.

- 10 U.S. Code § 10102.

- 32 U.S. Code § 102.

- U.S. Department of Defense, National Guard Bureau, 2015 National Guard Bureau Posture Statement, p. 6, http://www.nationalguard.mil/portals/31/Documents/PostureStatements/2015%20National%20Guard%20Bureau%20Posture%20Statement.pdf (accessed August 15, 2015).

- 32 U.S. Code 10501–10502.

- Adjutants General Association of the United States, “Message from the President,” http://www.agaus.org (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. Department of Defense, 2015 National Guard Bureau Posture Statement, p. 15.

- Army National Guard, “Army National Guard History,” current as of March 2013, http://www.nationalguard.mil/Portals/31/Features/Resources/Fact%20Sheets/new/General%20Information/arng_guard.pdf (accessed August 17, 2010).

- U.S. Army, U.S. Army Reserve at a Glance, pp. 4–6, http://www.ncfa.ncr.gov/sites/default/files/ArmyReserveataGlance.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 131.

- Lieutenant General Jeffrey W. Talley, Chief of the Army Reserve; Chief Warrant Officer 5 Phyllis Wilson, Command Chief Warrant Officer of the Army Reserve; and Command Sergeant Major Luther Thomas Jr., Command Sergeant Major of the Army Reserve, The United States Army Reserve 2015 Posture Statement, p. 5, http://docs.house.gov/meetings/AP/AP02/20150317/103117/HMTG-114-AP02-Wstate-TalleyJ-20150317.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. Department of Defense, 2015 National Guard Bureau Posture Statement, p. 17.

- Ibid., pp. 21–23.

- North American Aerospace Defense Command, “Continental U.S. NORAD Region,” http://www.norad.mil/AboutNORAD/ContinentalUSNORADRegion.aspx (accessed September 4, 2015).

- U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Fiscal Year (FY) 2014 President’s Budget: Justification for Component Contingency Operations, the Overseas Contingency Operation Transfer Fund (OCOTF), May 2013, p. 13, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2014/FY2014_Presidents_Budget_Contingency_Operations%28Base_Budget%29.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Fact Sheet, “1st AF Mission,” U.S. Air Force, CONR-1AF (AFNORTH), January 14, 2015, http://www.1af.acc.af.mil/library/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=4107 (accessed August 17, 2015).

- See, for example, Lieutenant General James F. Jackson, Chief of Air Force Reserve, “Fiscal Year 2016 Air Force Reserve Posture,” statement before the Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate, April 29, 2015, pp. 5–7, http://www.appropriations.senate.gov/sites/default/files/hearings/042915%20Lieutenant%20General%20Jackson%20Testimony%20-%20SAC-D.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Fact Sheet, “Air Force Reserve Command,” U.S. Air Force, February 19, 2013, http://www.afrc.af.mil/AboutUs/FactSheets/Display/tabid/140/Article/155999/air-force-reserve-command.aspx (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Ibid.

- Lieutenant General James F. Jackson, Chief of the Air Force Reserve, “Air Force Reserve Posture Statement,” statement before the Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, April 2, 2014, p. 7 (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Air Force Reserve, “Mission: Airlift,” https://afreserve.com/about/missions/airlift (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Air Force Reserve Command, “Timeline 2000–Present,” http://www.afrc.af.mil/AboutUs/AFRCHistory/TImeline2000-Present.aspx (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Committee Print, Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015: Legislative Text and Joint Explanatory Statement to Accompany H.R. 3979, Public Law 113-291, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, 113th Cong., 2nd Sess., December 2014, p. 60, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CPRT-113HPRT92738/pdf/CPRT-113HPRT92738.pdf (accessed September 5, 2015).

- U.S. Navy, “About the Reserve: Structure,” http://www.navy.com/about/about-reserve/structure.html (accessed June 9, 2015).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- U.S. Department of the Navy, Highlights of the Department of the Navy FY 2016 Budget, February 2015, p. 3-10, http://www.secnav.navy.mil/fmc/fmb/Documents/16pres/Highlights_book.pdf (accessed September 5, 2015).

- Vice Admiral Robin R. Braun, Chief of Navy Reserve, statement before the Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Appropriations, U.S. Senate, April 29, 2015, pp. 2–3, http://www.appropriations.senate.gov/sites/default/files/hearings/042915%20Vice%20Admiral%20Braun%20Testimony%20-%20SAC-D.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- House Report No. 114-102, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, 114th Cong., 1st Sess., May 5, 2015, p. 125, https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/114th-congress/house-report/102/1 (accessed September 5, 2015)

- U.S. Marine Corps, “U.S. Marine Corps Forces Reserve,” http://www.marforres.marines.mil/About/MediaInfo/MediaInfoFrequentlyAskedQuestions(FAQs).aspx#How_many_Reserves_have_been_activated_since_Sept._11,_2001_ (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. Marine Corps, “U.S. Marine Corps Reserve: Major Subordinate Commands,” http://www.marforres.marines.mil/ (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. Marine Corps, “U.S. Marine Corps Reserve: 4th Marine Division, Subordinate Units,” http://www.marforres.marines.mil/MajorSubordinateCommands/4thMarineDivision.aspx (accessed August 17 9, 2015).

- U.S. Marine Corps, “U.S. Marine Corps Reserve: 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, Subordinate Units,” http://www.marforres.marines.mil/MajorSubordinateCommands/4thMarineAircraftWing.aspx (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. Coast Guard, “Posture Statement,” last modified February 2, 2015, http://www.uscg.mil/budget/posture_statement.asp (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. Coast Guard Reserve, “About the Reserve,” http://www.uscg.mil/reserve/aboutuscgr/policy_statement.asp (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Alice R. Buchalter and Seth Elan, “Historical Attempts to Reorganize the Reserve Components,” A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, under an Interagency Agreement with the Commission on the National Guard and Reserves, October 2007, p. 11, https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/pdf-files/CNGR_Reorganization-Reserve-Components.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015)..

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 12.

- Lewis Sorley, “Reserve Components: Looking Back to Look Ahead,” Joint Force Quarterly, Issue 36 (December 2004), pp. 19–20, http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/jfq/jfq-36.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015) (internal footnotes omitted).

- James Jay Carafano, “The Army Reserves and the Abrams Doctrine: Unfulfilled Promise, Uncertain Future,” Heritage Foundation Lecture No. 869, April 18, 2005, http://www.heritage.org/research/lecture/the-army-reserves-and-the-abrams-doctrine-unfulfilled-promise-uncertain-future.

- Andrew Feickert and Lawrence Kapp, “Army Active Component (AC)/Reserve Component (RC) Force Mix: Considerations and Options for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, December 5, 2014, pp. 4–5, http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R43808.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

- U.S. General Accounting Office, National Guard: Peacetime Training Did Not Adequately Prepare Combat Brigades for Gulf War, GAO/NSIAD–91–263, September 1991, http://www.gao.gov/assets/160/151085.pdf (accessed September 4, 2015).

- National Guard, “About the Army National Guard,” http://www.nationalguard.mil/AbouttheGuard/ArmyNationalGuard.aspx (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Ibid.

- Rebecca Autrey, “Odierno: Right Balance Sought for Active, Reserve Components,” National Guard Association of the United States, January 8, 2014, http://www.ngaus.org/newsroom/news/odierno-right-balance-sought-active-reserve-components (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Devin Henry, “Lean Times at the Pentagon Pit Active-Duty Army Against National Guard,” MinnPost, March 27, 2015, https://www.minnpost.com/dc-dispatches/2015/03/lean-times-pentagon-pit-active-duty-army-against-national-guard (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Traditionally, Guard and Reserve Component units drill one weekend a month and two weeks each summer or 39 days a year. In reality, most of their members dedicate much more time to their units.

- For a detailed discussion and analysis of the Active/Reserve component balance issue as it relates to the Army, see Feickert and Kapp, “Army Active Component (AC)/Reserve Component (RC) Force Mix: Considerations and Options for Congress.”

- Daniel Gouré, “The National Guard Must Again Become a Strategic Reserve,” Lexington Institute, June 21, 2013, http://lexingtoninstitute.org/the-national-guard-must-again-become-a-strategic-reserve/ (accessed August 17, 2015).

- National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force, “Background,” http://afcommission.whs.mil/about (accessed August 17, 2015).

- National Commission on the Structure of the Air Force, Report to the President and Congress of the United States, January 30, 2014, p. 7, http://afcommission.whs.mil/about (accessed August 17, 2015).

- Ibid., p. 8.

- National Commission on the Future of the Army, “Background,” http://www.ncfa.ncr.gov/content/background (accessed: August 17, 2015).

- Ibid.