What makes the economy grow?

Everyone should want the economy to grow. A growing economy puts more money in families’ pocketbooks and charities’ budgets, the poor and unemployed have an easier time finding jobs, and families saving for retirement or their children’s education can see their nest eggs grow.

So what makes the economy grow? You don’t need a degree in economics to answer this, you just need to think carefully. Common sense can help expose some popular but mistaken myths about the economy.

Many think of our economy as if it were a big apple pie with that flaky criss-cross crust on top. You can slice the pie this way or that. You can cut eight or 10 or 12 equal slices, or you can cut some slices thinner than others.

If you cut one of the slices really thick, though, you’ll have to cut the other slices thinner. It’s a trade-off. So it seems unfair that some should have more than others. It seems fairer to slice the pie into equal slices.

But this idea is fatally flawed. First, our economy isn’t like an apple pie sitting on the counter getting cold. With the right conditions, we can create more wealth: That is, we can make the pie grow. Some create more than others and may end up with bigger slices; but in the long run, everyone can end up with a bigger slice than they would have had otherwise. That’s a win-win.

Our economy isn’t like an apple pie sitting on the counter getting cold. We can create more wealth: That is, we can make the pie grow. Some create more than others and may end up with bigger slices; but in the long run, everyone can end up with a bigger slice than they would have had otherwise.

The second problem with the apple pie idea is this: Who’s doing the slicing? Usually that task is assigned to the federal government, but the government didn’t bake the pie in the first place. American work and ingenuity did that. So when government tries to slice the pie into equal pieces, it’s simply spreading income around by taking from some and giving it to others. At best, that’s win-lose. And by picking winners and losers, such a policy distorts the incentives that lead those who produce more to do their best, which means they produce less, they earn less, and the pie shrinks.

Trying to spread income around by redistributing what people have earned through their own efforts actually hinders the creation of new income. And creating more income—growing the pie—is the only known way to increase overall prosperity.

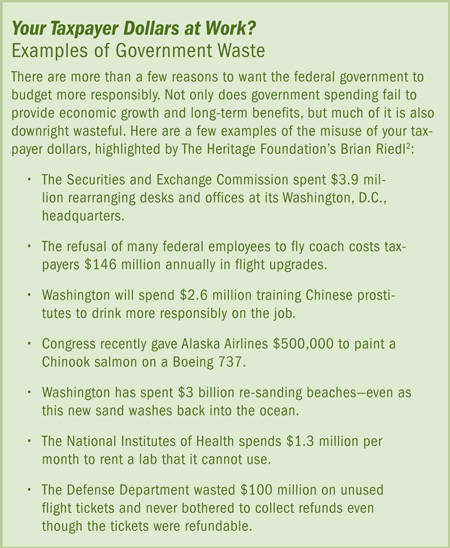

Fortunately, we know how to grow the economy—how to make the pie bigger: by individuals working and trading and creating freely, not by government taxing away our income, restricting our economic freedom, and spending our money supposedly on our behalf but really on its own priorities.[1]

Think of a dozen engineers at Apple Computer who invent an easier way to find information on the Web, which Apple then includes on its new, wildly popular iPhone. Millions of people buy and enjoy the new iPhones, providing jobs for Apple employees and money for future research at Apple. New income and wealth has been created.

Similarly, when a farmer tends an apple orchard and then sells the apples, he gets money to buy what he needs for his own use and to sustain his apple business, while customers get the apples, which they prefer to the money they give the farmer. Income has been created by developing products that consumers want. If the farmer saves rather than spends some of the proceeds, he can invest the money and create even more income in the future.

This isn’t rocket science. It’s common sense, and it’s been true for thousands of years. But in Washington, unfortunately, it’s not very common. In an economic downturn, it becomes downright rare. Many lawmakers use temporary downturns to increase their power permanently by taxing, spending, and borrowing rather than supporting policies to grow the economy.

Of course, some of the federal government’s work—such as administering the judicial system and maintaining national security—is vital to society and the economy. But income redistribution and other forms of government meddling often shrink the pie or keep it from growing. They take income away from those who earned it and give it to those who didn’t. In the process, they divert resources to less productive uses and thus impede the creation of new opportunities that would otherwise benefit everyone in the long run.

For instance, when the government imposes a tax and takes income from Apple Computer or the apple farmer and hands it over to somebody else, it is merely redistributing—not creating—income. Total income has not increased by one penny, and the government has discouraged both Apple and the farmer from creating more products of value to others.

So what really does make the economy grow?

The economy grows when individuals and businesses succeed in recognizing new markets and new opportunities and accept the risks involved in pursuing these opportunities in the hope of earning income. Each of these elements is important, like a recipe of many ingredients. The absence of any ingredient would diminish the taste of the dish. For example, the economy grows when someone sees an opportunity to meet a need and can marshal the resources to meet that need. That need may be to supply an existing good to a new market, or it may be to supply something brand-new, like Apple Computer’s iPhone in the example above.

The economy grows when individuals and businesses succeed in recognizing new markets and new opportunities and accept the risks involved in pursuing these opportunities in the hope of earning income. Each of these elements is important, like a recipe of many ingredients. The absence of any ingredient would diminish the taste of the dish. For example, the economy grows when someone sees an opportunity to meet a need and can marshal the resources to meet that need. That need may be to supply an existing good to a new market, or it may be to supply something brand-new, like Apple Computer’s iPhone in the example above.

For the supplier to meet the need, however, there must be a marketplace in which the supplier can meet potential buyers and where they can settle on a price. The supplier knows there will be risks involved, and so must have some confidence about a whole range of issues to be willing to accept those risks. For example, he must be confident that his goods won’t be stolen by someone else or confiscated in whole or in part by the government, and he must have some confidence that the customers will be in the market and willing to pay an adequate price.

When these elements are in place, individuals invest in their own abilities through education and training, and so increase their value to the market. When these elements are in place, businesses invest in new production facilities in the hope of expanding the quantity or range of their products and to employ the latest technologies to reduce cost.

Importantly, economic growth is not the consequence of some master economic plan managed by the government. It results from millions of people individually seeking what is in their own interests by providing what is in the interests of others. The collective consequence of their actions, under a stable rule of law, is to increase the number of jobs in the economy, the wages earned by workers, and the income and wealth of the nation.

The economy grows when individuals and businesses succeed in recognizing new markets and new opportunities and accept the risks involved in pursuing these opportunities in the hope of earning income.

But lawmakers rarely admit these realities. The idea of transferring income from families and businesses to government gets repackaged in all sorts of creative but deceptive ways. We hear talk about stimulating the economy, creating jobs, putting people back to work, bailing out allegedly vital industries, and making the rich pay their “fair share.” Though these myths are all variations on the same theme, let’s deal with them one at a time.

Growing the Economy: Separating the Myths from the Facts

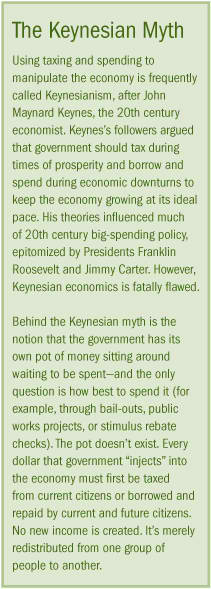

MYTH #1: Government spending grows the economy by pumping new money into it.

FACT: Every dollar that government “injects” into the economy must first be taxed or borrowed from families, businesses, or other nations.

In tough economic times, lawmakers often launch new spending programs to rev up growth by “injecting” money into the economy. But this approach does not increase production or create new income; it only moves money around within the economy. In other words, it does not encourage growth in either the overall economic pie or the family bank account.

Think of your family’s savings. If you want to increase your investments in a savings account without earning more money or taking out a loan that must be repaid, then you have to take that money from another part of your savings, such as your checking account. You haven’t increased your savings; you’ve just shifted existing savings around.

The same logic applies to government spending. Governments don’t create new income out of thin air. When Congress funds spending with taxes or by borrowing, it is not creating new income; it is merely redistributing existing income.

Because government must first take or borrow money from people before spending it, the claim that pumping new money into the economy will grow the economy is ill-founded.

MYTH #2: Government spending makes people more productive.

FACT: Government spending often encourages behavior that has bad economic consequences.

Many government programs lead to choices that actually make the economy worse. Welfare programs, for example, generally encourage recipients to rely on government handouts rather than to work. This is why welfare reform efforts that require recipients to find work tend to succeed: They encourage choices that help both the individual and the community. Work gives people dignity because it allows them to become more self-sufficient rather than depending on government assistance. And their work makes the economy more productive.

In another example, federal flood insurance programs encourage people to take undue risks by building houses in flood plains. How many people would actually build on a flood plain without insurance against floods? Some private insurers would accept such a risky venture, but only by charging a far higher premium for the insurance. The government takes on this risk while letting taxpayers foot the bill.

Besides encouraging bad choices, government programs often discourage good economic choices, such as investment and personal savings for the future. For example, government programs that cover retirement (like Social Security and Medicare), housing (the low-income housing tax credit), and higher education expenses (Pell grants) discourage saving. Why should people set aside funds for big-ticket expenses such as college and retirement that government says it will pay for? Other government programs—such as Medicaid, which funds health care for the poor—have eligibility rules that encourage individuals to keep their incomes lower in order to qualify.

Does this mean that society and individual citizens should do nothing to help the poor and unemployed? Of course not. But we have to weigh the real economic costs of government-controlled programs, especially income-transfer schemes, against their real—as opposed to promised or imagined—benefits. If lawmakers actually did this, few of these programs would exist in their current forms, since most do more harm than good.

Instead, government spending should focus on some very specific things that can improve our productivity. In some cases, for example, additional spending on infrastructure can reduce transportation costs and increase productivity within the transportation sector, which then permeates much of the rest of the economy.

Government spending on basic research can also increase incomes and productivity in the long run. Basic research is often exceptionally high-cost, is highly uncertain, and typically generates returns many years after the initial investment (think of the space program, for example). These factors discourage the private sector from investing adequately in basic research and provide a rationale for government spending in strategic research areas.

MYTH #3: The federal government should bail out faltering industries and states to revive the economy.

FACT: Bailouts harm the economy because they reward reckless private and state spending, leaving it unchecked and effectively encouraging more of the same in the future.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle once said, “If you want to encourage something, reward it. If you want to discourage it, punish it.” His words ring true 2,500 years later.

Bailouts for private companies usually mean that failing businesses receive taxpayer money, while their more successful competitors do not. Does that make any sense? In the real world, investors seek to put their money where it is most valuable; that is, in companies that succeed, not those that fail. In the alternate world of government bailouts in which lawmakers spend taxpayer money rather than their own, failure is rewarded and success is punished.

With the frenzy of bailouts for private companies, states have tried to hop aboard the federal bailout gravy train to close budget gaps that result from their own overspending. After spending beyond their means, they then argue that it would be in the best interests of their taxpaying citizens to get a bailout from the federal government.

A federal bailout of the states, however, would transfer money from families in states that have resisted extravagant spending programs to other states that have spent more recklessly. This makes no sense.

Imagine you have two sons, Peter and Paul, and you give each a weekly allowance. Paul spends his whole allowance on the first day; Peter budgets so that he’ll have spending money throughout the week. Would you take money from Peter, who saved, to pay Paul, who spent? Of course not. That would not only be unjust; it would teach both boys that careless spending will be rewarded.

In the same way, it’s wrong to force families who have elected responsible stewards in their states to pay for the folly of those in other states who have elected irresponsible spenders.

Moreover, such schemes encourage responsible states to be less responsible next time. When they can simply withdraw whatever money they want from the federal ATM—money that has been earned by families in all 50 states—why bother budgeting responsibly? Their attitude becomes one of spend now, bailout later.

Recent history bears this out. Because most states depend on income tax revenues—which vary a lot from year to year—common sense tells us that they should save during booms to cushion the inevitable recessions. Instead, many states keep responding to temporary revenue surges with new permanent spending programs which leave them in the red when the economy slows.

Between 1994 and 2001, for instance, most states were flush with new revenues. But instead of building up rainy-day funds, many expanded their general-fund budgets. Collectively, they increased spending by 6.2 percent annually. All booms eventually end, however, and these free-spending states were unprepared for the 2002–2003 economic slowdown. Rather than paring back their bloated budgets, they demanded and received a $30 billion bailout from Washington in 2003. Guess what happened next? After the 2003 bailout, states went right back to spending—with states’ annual budget hikes averaging 7.2 percent over the next four years.[3] Encouraging such behavior is not only foolish; it is also wrong.

Congress should resist such bailouts and instead leave state governments to set priorities, make trade-offs, and reduce unnecessary spending. And states that insist on deficit spending should not demand that Washington plunder responsible states on their behalf.

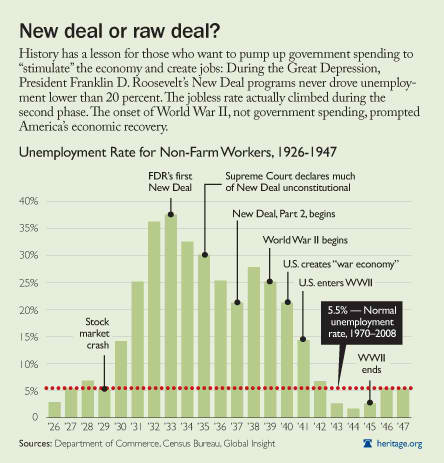

MYTH #4: Public works projects stimulate the economy by creating new jobs.

Fact: In the short run, public works projects have no real effect on overall unemployment. They simply displace resources that could be used to create jobs in the private sector and move those resources to the government payroll.

The myth of public works spending can be best explained by looking at highway spending. In order to spend money hiring road builders and purchasing asphalt, the government must tax or borrow that money from other sectors of the economy. This limits growth in those sectors and crowds out job creation.

The myth of public works spending can be best explained by looking at highway spending. In order to spend money hiring road builders and purchasing asphalt, the government must tax or borrow that money from other sectors of the economy. This limits growth in those sectors and crowds out job creation.

Again, this should be common sense. Suppose a family is saving money to build a swimming pool. This would, of course, provide work for the contractors and workers who would build the pool. Now suppose the family learns that they are expecting a new baby. They decide that a swimming pool would be too dangerous with a little one around, and what they really need is an addition to their house. So, instead of hiring people to build the pool, they hire people to build the addition. This provides work for laborers on the addition, but it is instead of, not in addition to, the work that would have been done by the pool builders.

Public works schemes are like this, except that they often do more harm than good. That’s because, like state bailouts, public works projects tend to direct resources to less productive, inefficient projects like “bridges to nowhere” (a boondoggle recently proposed by Congress). Public works projects require significant bureaucracy and red tape, and there is often little accountability and motivation for efficient use of taxpayer dollars. This hinders economic growth, which ultimately is about increasing productivity.

MYTH #5: Tax cuts simply pad the pockets of the rich without helping a weak economy.

FACT: Smart tax cuts encourage work, savings, and investment to help stimulate economic growth that benefits people across the board.

Some argue that cutting taxes and tax rates doesn’t help a weak economy and might even make it worse by increasing deficits. This ignores the way in which people at all income levels benefit when the overall economy grows—which happens when taxes are cut and people have more money in their pockets. As we have seen, government spending does not increase income; it merely diverts income from some people to others.

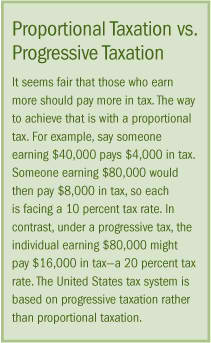

The United States has what is called a progressive income tax. This means that, as a family’s income rises, so does the rate at which their income is taxed. The last dollar earned is taxed more heavily than the first dollar. This is different than a proportional tax in which taxes would increase proportionally with incomes (see sidebar for further explanation). A progressive system does far more damage to incentives that generate economic growth such as working, saving, and investing.

Progressive taxation is problematic because it decreases the incentive for people to be productive and generate wealth for themselves and the economy. For example, suppose a parent pays a child an hourly wage for helping around the house, but the wage decreases after each hour. The child’s motivation will wither along with his hourly wages.

A progressive tax creates the same problem in the adult world. For the economy to grow, businesses must either produce increasing amounts of goods and services or create new ones. This in turn requires consistently higher investment in new production facilities and technologies and a motivated, productive workforce—therefore businesses and individuals must have financial resources to invest. Yet imposing higher tax rates on the last dollars earned shrinks the amount of money a worker keeps as he creates more value. These taxes discourage all of the wealth-creating activities mentioned above, since the last dollars earned are the ones most likely to be saved and invested rather than consumed.

Think of it this way: You spend your first dollars on necessities like food and rent, which everyone needs; but the more you earn, the more of your additional income you can save and invest—but also the more tax you pay. That’s why lower tax rates on those dollars encourage working and saving, which, in turn, grow the economy.

History confirms common sense. High tax rates were reduced during the 1920s, 1960s, and 1980s. In all three decades, lower tax rates contributed to increased investment, and robust economic growth followed: The economy grew by 59 percent from 1921 to 1929, 42 percent from 1961 to 1968, and 34 percent from 1982 to 1989.[4]

But lawmakers often reject tax cuts and spending restraint that foster long-term economic growth. Instead they propose stimulus gimmicks to “put money in people’s pockets” and “get people to spend money.” They are counting on taxpayers to notice the check in the mail while markets ignore the borrowing that financed the check.

Take past tax “rebates” as an example. Washington borrowed billions from investors and then mailed that money to families. In 2001, typical families received $600; in 2008, it was $1,200. This simple transfer of borrowed money had a predictable effect: The consumer spending rate went up, while investment spending went down. No new income was created because the so-called rebates did not increase productive behavior: No one had to work, save, or invest more in order to receive a rebate. Does anyone really believe that we can improve our economy by borrowing and consuming more and saving and investing less?

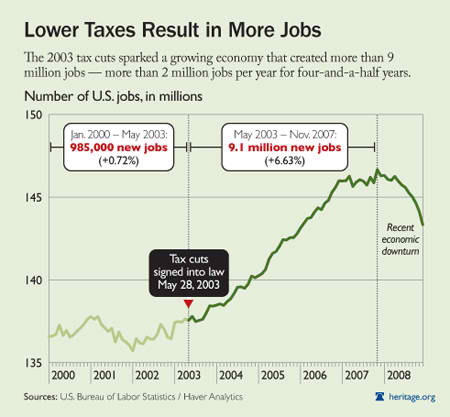

In contrast, the 2003 tax cuts reduced unemployment and helped grow the economy since they encouraged long-term productive behavior.[5] But this success was not well reported. By contrast, there has been much more commotion over fake stimulus schemes that only put money in consumers’ pockets for the short run.

Reporters and lawmakers should ask which policies will best encourage the work, savings, and investment needed to expand the economy’s capacity for growth. Such growth benefits not just the rich, but also those looking for jobs, saving for their kids’ educations, or simply hoping to increase their earnings from hard work.

Opportunity for All

“As they say on my own Cape Cod,” President John F. Kennedy was fond of noting, “a rising tide lifts all the boats.” President Kennedy meant that overall economic growth benefits everyone. That’s why one of his major acts as President was to slash the top income tax rate from 91 percent to 70 percent, helping to trigger the increased prosperity of the 1960s.

Government policies can have a huge effect on the U.S. economy—and on the family bank account. Policies that try to transfer income from one group to another are based on myths, not reality. They do far more harm than good. In contrast, if public officials will pay attention to the lessons of history and common sense, avoid short-term “stimulus” gimmicks, and instead enact reality-based economic reforms, they can put the country back on the road to sustained prosperity.

To read more on these topics, see:

- Brian M. Riedl, “Ten Myths About the Bush Tax Cuts,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 2001, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/Taxes/bg2001.cfm.

- Bill Beach, Rea Hederman, and Tim Kane, “The 2003 Tax Cuts and the Economy: A One-Year Assessment,” Heritage Foundation WebMemo No. 543, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/Taxes/wm543.cfm.

- Daniel J. Mitchell, “The Impact of Government Spending on Economic Growth,” Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1831, at http://www.heritage.org/Research/Budget/bg1831.cfm.

- Jay W. Richards, Money, Greed, and God: Why Capitalism is the Solution and Not the Problem (HarperOne, 2009), chapters 3 and 4.

- The Heritage Foundation’s 2009 Index of Economic Freedom, at http://www.heritage.org/index/.