The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently reported that the consumer price index rose 8.2% in September compared with the year before, but that national average hides the fact that prices are rising faster and higher in certain parts of the nation.

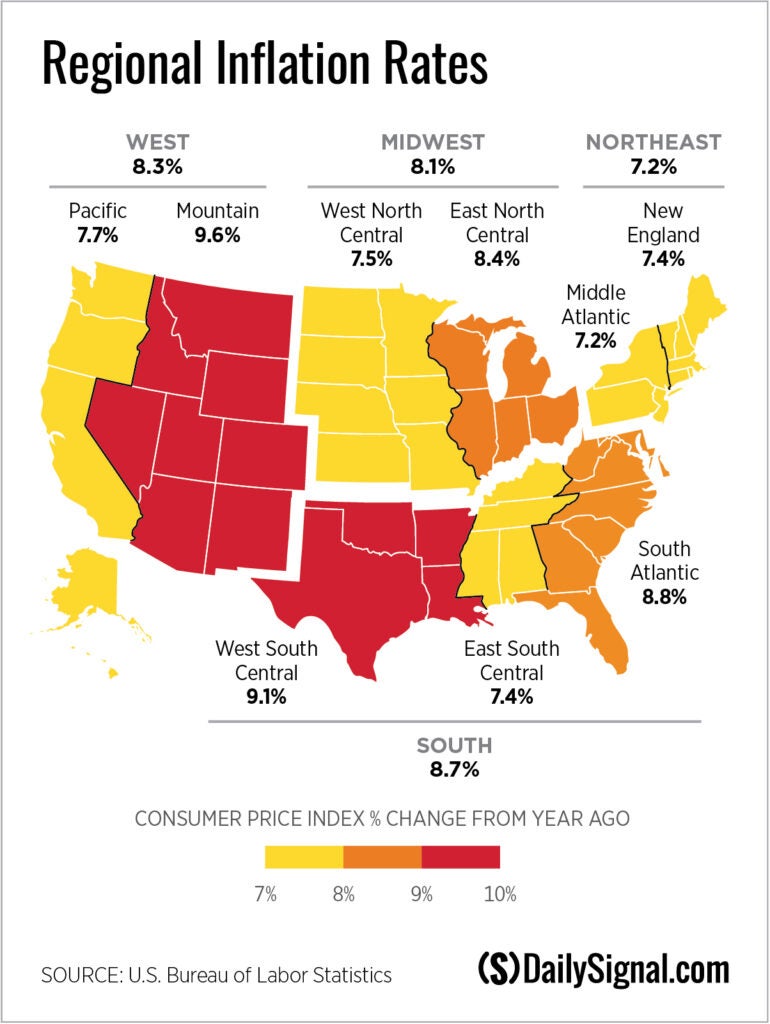

Breaking the country into the same subregions used by the Census Bureau, the rate of price increases that consumers pay for goods ranges from 7.2% in the Northeast to 9.6% in the Mountain States.

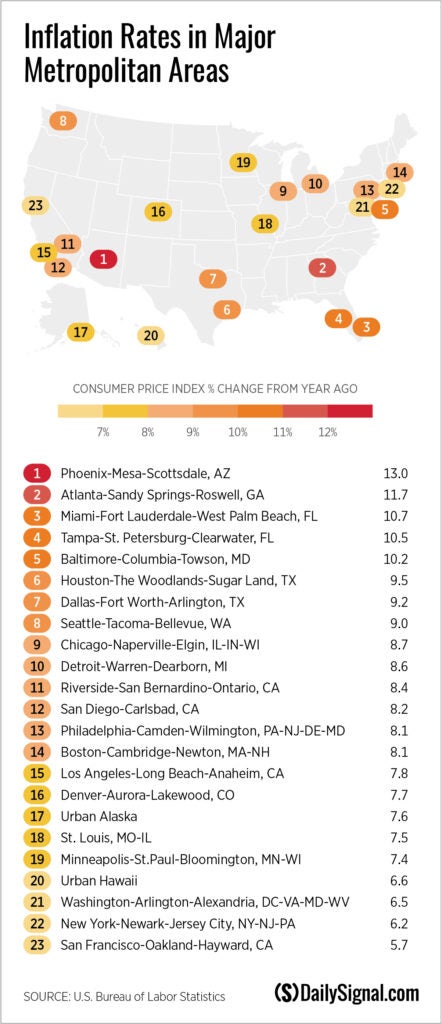

More local measures show an even greater range in price increases, from 5.7% in metropolitan San Francisco to 13% in metropolitan Phoenix.

Food, energy, and transportation are some of the fastest growing categories. Transportation costs are up across the country, with increases around 13% in metropolitan areas with both the highest and lowest overall inflation rates. The increase in food and beverage costs vary slightly among locations.

Nationally, housing costs seem to be growing at moderate rates, obscuring that housing costs are growing quickly in some areas and slowly in others as Americans reshuffle where they live.

Since housing comprises more than 40% of the consumer price index, changes in rents and home prices can have a substantial impact on the inflation figure for both the nation and individual regions. The cities and states with the fastest increases in housing costs also tend to have the highest inflation rates.

Housing costs grew by 17.1% in Phoenix, by 12.8% in Atlanta, and by 13.5% in Miami. Meanwhile, housing costs rose by only 3.5% in San Francisco, 4.9% in New York City, and 5.6% in metropolitan Washington. Housing costs include both shelter and fuels and utilities.

Are housing costs rising because of shrinking supply or growing demand? Areas with strict zoning and open-space laws have a restricted supply of housing, which puts upward pressure on prices.

But most of those restrictions were in place before the inflation we began to see last year and are reflected in high price levels. Areas that already have higher prices tended to see low inflation, as in San Francisco, New York City, and the Washington metropolitan area.

The data would suggest that faster price hikes result when new residents increase demand by moving to vibrant, growing cities faster than new housing can be built.

A recent census report on domestic migration shows that the South is growing in population while other regions are shrinking. Sure enough, six of the seven metropolitan areas in the South are six of the seven metro areas with the highest inflation.

It makes sense that housing explains a significant amount of regional variation in inflation. Food and fuel can be moved from one location to another when shortages drive up prices. However, housing is fixed in place.

The dramatic rise in housing costs follows major spending bills from Congress that mostly were paid for by the Federal Reserve’s monetizing of new debt, sometimes referred to as “printing money.” That action allowed many Americans to move to areas that used to have relatively low costs of living at a pace much faster than new housing could be built.

Many states have exercised fiscal responsibility and fostered robust economic growth along with a lower cost of living by keeping taxation, regulation, and government spending in check at the state and local levels.

The benefits of responsible state governance have been undone somewhat by inflation, which was caused in the nation’s capital and has fallen disproportionately on cities and states that worked so hard to create affordable communities.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal