The Index of U.S. Military Strength: Ten Years in Review

Dakota L. Wood

The future cannot be predicted, but it is knowable. Trends are not linear or unchangeable as they stretch into the future, but they do illuminate truths and stubborn consistencies in behavior, interests, and the realities of war and what is needed to prepare for it so as to deter it or win it when forced to engage in it. That is the focus of this essay.

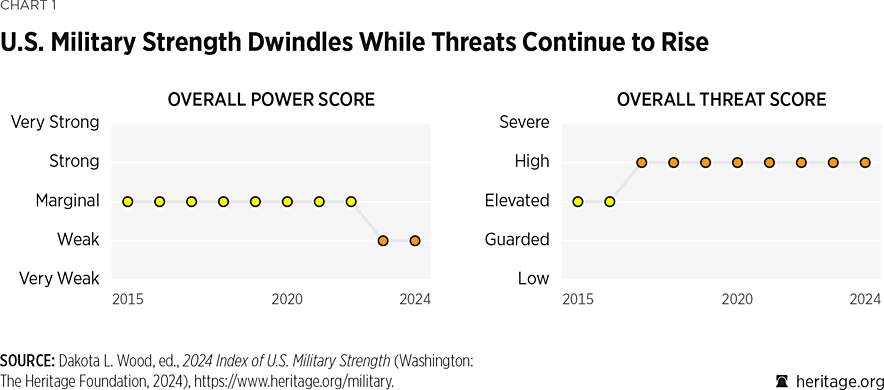

A decade of reporting on anything is enough time to get a feel for trends: whether something is headed in the right direction or you have something about which you should be worried. When it comes to the U.S. military and the ability of the United States to defend its interests in the world that is rather than the world we wish we had, the trends irrefutably show that the U.S. has something about which to be worried.

The ability of a military force to win in battle is only partly a function of its training, morale, and modernity of equipment. Success in war is also a function of how much capability a force has (its capacity) relative to its enemy and the setting within which the battle occurs. If the battle is close to home, it is much easier for the force to be resupplied, reinforced, or supported with long-range weapons. Usually, a fight close to home or near allies gives the force access to bases, ports, and airfields. Conversely, the farther the fight is from home and from allies and supporting infrastructure, the harder it is for the military to continue fighting or even operating as combat exacts its toll. Supplies of munitions, fuel, food, and repair parts begin to dwindle. It gets harder to replace destroyed equipment and combat platforms. The morale of the force becomes more difficult to buoy as the men and women involved suffer the ravages of battle while knowing that relief is distant, contested, and limited by time and space.

If allies are net contributors, U.S. shortfalls can be mitigated. This presumes, of course, that allies can sustain their own efforts in the first place. Unfortunately, recent history says they cannot. Every ally that has supported coalition efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere has needed help getting people, equipment, and supplies to the theater and to sustain the flow of logistical resupply over time. The U.S. is one of a very few countries equipped with long-distance cargo aircraft and the aerial refueling planes needed to establish an air bridge to and within an operational theater.1

Allies and Adversaries

Since almost all major military actions since the end of the Cold War have taken place far from Europe—the 1990s crises in the Balkans and the current war in Ukraine being the exceptions—U.S. and allied forces have not had the benefit of ports, airfields, and support bases that were close at hand; they have had to build their own or gain permission from a nearby country that was willing to allow its infrastructure to be used for such operations. In other words, the U.S. has had to support not only itself, but the allies it has called upon to contribute to such efforts.

The value of allies fighting alongside U.S. forces is more than the raw combat power they provide; the political validation of military actions is often essential, and allies typically bring national and operational intelligence capabilities and regional connections that make the overall force more capable. But in military terms, allies tend to be a logistical burden on combined military action rather than a relief to U.S. capabilities. Thus, knowing whether U.S. allies are increasing their ability to contribute to combined efforts or are falling further behind is quite important.

Knowing the trends among likely adversaries is similarly important: Are they improving their capabilities through investments in various forms of military power, or is their condition eroding over time? It is nearly impossible to predict whether an expansion in capability or the modernization of weapons translates into battle competence and military advantage. These are revealed only in actual combat. But one can be fairly certain that the more equipment a competitor fields, the longer he will likely be able to sustain operations because a large inventory of materiel enables him to replace combat losses, a large inventory of munitions enables him to apply volume-of-fire against his enemy, and large investments to improve the capacity, capability, and (presumably) readiness of his force imply seriousness about military power.

Russia’s war against Ukraine is instructive. Though Russia’s extremely poor performance has surprised most analysts and observers, the sheer size of its inventory of vehicles, aircraft, people, and especially munitions has enabled it to sustain its assault on Ukraine since late February 2022 in spite of strategic and operational incompetence. Western support has enabled Ukraine both not to lose and to impose substantial losses on Russia, but Russia has leveraged its vast quantities of materiel to remain in the fight, even pulling 1950s vintage tanks from storage.2 One can scoff at such relics being committed to modern combat, but a T-54 tank on the battlefield is still better than a modern British Challenger II sitting in a vehicle lot in England.

The point here is that investments in military forces that expand capacity can offset shortfalls in quality (to an extent) and competence. Russia’s military leaders have badly mismanaged both the invasion and many of the operations that have taken place since then, yet the Russian military still occupies one-fifth of Ukraine, has destroyed much of the country, and has imposed several hundred thousand casualties, both military and civilian, on Ukraine and itself.

Capacity of force covers a multitude of sins in competence and capability. Referring again to the Russia–Ukraine war, Russian forces have often averaged 60,000 rounds a day of artillery fire3 to the Ukrainians’ 6,000 rounds,4 a 10-to-one advantage in volume even though Ukraine has often shown itself to be more innovative in action and has been supported by more advanced Western munitions and artillery (rocket and cannon) systems. Quantity can have a quality of its own.5 It is somewhat unfortunate, then, that the West—including the United States—places so much emphasis on quality that the increased cost results in the fielding of few platforms and weapons. The resulting force may be very modern but still have difficulty sustaining operations when attrition becomes a major factor.

Ten years of Index reporting6 clearly shows two things:

- America’s likely nation-state adversaries—China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea—have consistently invested in large quantities of military capability while also attempting to pace or surpass U.S. quality, and

- They are succeeding in some areas.

This is especially true with respect to munitions and for a compelling reason: Advances in relevant technologies (sensors, guidance systems, propulsion, and explosives) have made anti-platform weapons and munitions more effective at dramatically less cost than the platforms they are meant to destroy. This leads to the problem of salvo density (can one defend against a large quantity of incoming munitions?) and cost-imposition strategies (how good does a platform need to be, and at what cost, to survive against a barrage of comparatively inexpensive, precision-guided munitions?) that can place “better” militaries at a significant disadvantage. In fact, it is quite possible for advanced military forces to price themselves out of competition if the country is not willing to sustain a defense budget large enough to support capacity of capability.

Again, the Russia–Ukraine war, though not predictive of future war, is illustrative: Weaponized, remotely piloted drones costing several hundred to perhaps a few thousand dollars have been used consistently to destroy multimillion-dollar armored vehicles, including main battle tanks. Does this mean armored vehicles are obsolete? No, but it does suggest that any modern force will have to account for equipment inventories that include enough armor to absorb such losses while also being equipped with updated defensive capabilities that mitigate such an attack vector.

The expense of war seems always to increase, not decrease, and expense increases even more with distance. This reality has implications for force capacity as well as for the geographical positioning of forces and the ability of countries’ industrial bases to equip, repair, and replace assets in a timely manner.

It is certainly the case that America’s competitors have been hard at work building capacity (larger forces and the industrial base that makes them possible) while also modernizing their forces over the past decade. The evidence is indisputable.

Ten years ago, the Index reported growing concerns within the West, and particularly within the U.S., about modernization efforts in China and Russia. Both countries had witnessed what the U.S. was able to do in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm (1990–1991), the first a six-month buildup of U.S.-led coalition forces in Saudi Arabia that enabled the second, a two-pronged offensive into Kuwait to drive out Iraqi forces sent there by Saddam Hussein to claim the country as a province of Iraq.

Initiated with a 42-day air campaign of more than 100,000 attack sorties, followed by a massive ground campaign that lasted a mere 100 hours,7 the war saw the first widespread use of precision-guided munitions (PGMs) and stealth aircraft. The rapidity, devastating effectiveness, and scale of Operation Desert Storm were a grand testament to the force built in the 1980s to defeat Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces in Europe. It was followed in the mid-1990s by NATO operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina in which PGMs were again used with astonishing accuracy.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S., assisted by a broad coalition of partner countries, launched operations into Afghanistan, nearly seven thousand miles from New York City; Shanksville, Pennsylvania; and Washington, D.C., the sites where a total of 2,977 Americans were killed by al-Qaeda terrorists. That the U.S. was able to launch combat operations so far from home—initially, special operations forces supported by precision air strikes and, later, a large-scale deployment of conventional forces—and sustain operations for several years spoke to the capability of the U.S. military, something that no other military was able to contemplate much less execute. That America was also able to launch a second major operation from Kuwait into Iraq in 2003 doubly emphasized the importance of quantity.

Taking notice, China and Russia committed to modernizing their military power and professionalizing their forces, shifting from conscript militaries possessing aged, early Cold War equipment to forces loosely modeled on Western designs and reorganized to facilitate the type of joint, combined arms operations the U.S. preferred and with which it had arguably been successful in achieving initial war aims.

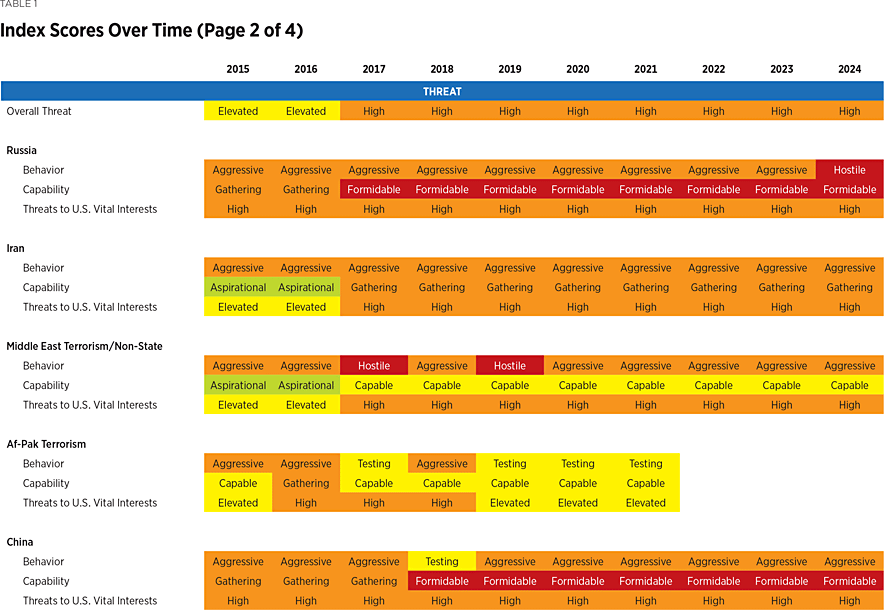

China: Power Projection and Provocation

Since 2015, China has significantly reorganized its military and reoriented it from an inward-looking force concerned primarily with internal security, with priority given to the army, to an outward looking, power projection–capable force that emphasizes air, naval, and strategic rocket forces. To solidify its claims over contested maritime features and waters, it undertook construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea and around the Spratlys (begun in 2014).8

In 2017, Beijing struck an agreement with Djibouti, a small country on the horn of North Africa, to construct China’s first foreign base,9 a naval base that gives it a perch on the strategically important Bab al-Mandab Strait that connects the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea and through which flows approximately five million barrels of oil and petroleum products each day.10

By 2020, China had enjoyed many years of sustained double-digit growth in its investments in defense capabilities, modernizing nearly all capabilities across all of its services. It also increased its military activities around Taiwan in response to that island’s 2020 election results that brought an independence-minded president into office, rammed and sank a Vietnamese fishing boat with one of its coast guard vessels, placed a sophisticated communications relay satellite into orbit, and landed a second probe on the moon.

Since 2022, China has grown its navy to a fleet of more than 360 ships; fielded fifth-generation stealth fighters (the J-20 and J-31, copies of the U.S. F-22 and F-35, respectively)11; developed a stealth bomber similar to the B-2; deployed four new Jin–class nuclear powered ballistic missile submarines; initiated construction of three fields of intercontinental ballistic missiles that will triple China’s inventory of nuclear-tipped ICBMs to 300; increased its stockpile of nuclear warheads to 400 or more; and developed a hypervelocity glide vehicle designed to evade U.S. missile defense capabilities.

With respect to Taiwan, China has increased its provocative, testing probes of and incursions into Taiwanese airspace and sea space in each of the past four years, penetrating Taiwan’s airspace 380 times in 2020, 960 times in 2021, and 1,727 times in 2022.

In 2022, China’s air force numbered 1,700 combat aircraft, 700 of which are considered fourth generation (equivalent to a U.S. F-16, F/A-18, or F-15). In 2022, it expanded its amphibious assault ship capabilities and quantities of long-range strike aircraft, cruise missiles, and bombers, all of which would be essential to any operation to take Taiwan by force or to cow it into submission. As if to prove the point, China operated 14 ships around the island in August 2022, and 12 ships and 91 aircraft rehearsed a blockade in April 2023. Chinese fishing and coast guard vessels constantly encroach within Taiwan’s 12 nautical mile limit. China is obviously serious about improving the capability and capacity of its military, driven by clarity of purpose and national objectives.

Russia: Expansion and Aggression

Russia—China’s neighbor, sometimes friend, but more often historical competitor—has been equally aggressive and intent on improving its military posture over the past decade. In 2014, Russia infamously seized Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, absorbing the bulk of Ukraine’s navy, the major port of Sevastopol, and the Sea of Azov.12 In 2014 and 2015, Russia increased its support for rebels in Ukraine’s Donbas region, restive Serbs in the Balkans, and disruptive activities in the Caucasus.

Russia also increased its investments in the Arctic, conducting large exercises in northern Arctic waters and orienting two-thirds of its navy toward that region. By 2024, Russia had reactivated, built, or improved six bases, 14 airfields, and 16 deepwater ports and fielded 14 arctic-capable icebreakers (10 times the number possessed by the U.S.13) along its northern coast.

From 2018 to the present, Russia has made substantial investments in missiles of all types as well as underwater weapons (for example, the Poseidon nuclear-tipped and nuclear-powered torpedo14); air and missile defense systems; anti-satellite capabilities; and a new RS-28 Satan 2 ICBM. During this period, Russian officials were accused of poisoning political enemies, and the government expelled diplomats and ordered the closure of the U.S. consulate in Saint Petersburg; strengthened relations with Egypt, Syria, Venezuela, and Iran; and committed to a creeping occupation of Montenegro.

As of February 2023, some 13,000 Russians had settled in Montenegro (a NATO member since 2017) since the start of the war against Ukraine one year earlier, arriving overland through Serbia. As was the case in Crimea and Donbas, Russia can be expected to push out or forcibly remove locals who are not to its liking and emigrate its own people to establish a population that is favorable to Moscow. Such actions occur below the level of war, do not draw a response from the West, and ultimately establish effective Russian control of an area.

Russia’s efforts to improve its military capabilities and the readiness of its forces were also reflected in very large military exercises. Snap (no-notice) exercises became common, augmenting announced mobilizations like the Zapad series in which Russia would deploy forces close to Ukraine for weeks of high-intensity training.

A major exercise in 2021 was especially worrisome because it was accompanied by intense rhetoric aimed at Ukraine. The exercise included combat enablers like expanded medical care and large quantities of blood supplies that have not normally been part of such an exercise; lasted much longer than usual; and included as many as 300,000 personnel (depending on how people are associated with the event) and 35,000 combat vehicles, 900 aircraft, and 190 ships. When it ended, Russia left a large amount of equipment and various support capabilities in place. When it invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Russia was able to leverage the materiel it had left close to the Russia–Ukraine border.15

Iran and North Korea: Growing Nuclear and Missile Capabilities

Iran and North Korea were similarly investing in capabilities and provocations to achieve their various objectives.

Iran was doggedly consistent in its behavior over the past decade. It was reliably supportive of terrorist organizations in the Middle East, notably Hezbollah and Hamas, emphasizing actions against Israel (mostly rocket attacks) and combat activity in Syria in support of Bashar al-Assad’s efforts against rebel challengers nominally supported by the West. As if to culminate a decade of Index reporting on the threat that Iran and its terrorist proxies present to the region, Hamas viciously attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, specifically targeting civilians, killing approximately 1,400 and injuring many more. Israel responded by declaring war on Hamas and undertook a military campaign of its own to eliminate Hamas as a threat to the country and its people.16 Encouraged by Iran, the escalation of attacks from Hamas and Hezbollah on Israel, in addition to provoking Israel’s military response, threatens to broaden the war to involve more combatants and escalate the war’s intensity—a perfect illustration of the very concern this Index has with the destabilizing effect that terrorist groups can have on regions of critical importance to the U.S.

Iran was certainly consistent in its harassment, interdiction, and occasional seizures of commercial ships moving cargo and petroleum products from the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz into the Gulf of Oman and larger Arabian Sea. In 2020, Iran allegedly damaged four tankers near the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and attacked two tankers in the Gulf of Oman. It escalated such activities over the next two years, harassing, attacking, or interfering with at least 18 ships transiting the area.

In 2020, in reprisal for the U.S. killing of General Qasem Soleimani, the leader of the Iranian Quds Force and interlocutor with Hezbollah, Hamas, and other terrorist organizations, Iran launched a missile attack against an Iraqi base that was hosting U.S. forces. It mounted another such an attack (this time by proxy) in 2022, equipping Houthi forces with two missiles with which they attacked the Al-Dhafra air base in Saudi Arabia, home to 2,000 U.S. service personnel.

Militarily, Iran was relentless in expanding its inventory of missiles—for many years the largest in the Middle East—and making qualitative improvements, especially in areas linked to its nuclear program. In 2020, it launched a military satellite into orbit using a vehicle (rocket) with features needed for a long-range military missile rather than a lift body for commercial payloads. A year later, the government revealed a new launch vehicle that could be launched from a mobile pad and was suitable for military rather than commercial or scientific use.

Iran also continued to obstruct international monitoring of its nuclear program, refusing to reinstall International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) monitoring devices it had unilaterally disabled in 2022. In February 2020, Iran was assessed to have 1,500 kilograms of low enriched uranium; in 2023, its stock of uranium had been enriched to 60 percent, the quantity (122 kg) sufficient to produce three nuclear warheads if enriched further to 90 percent.17

North Korea was also busy over the decade of Index reporting. As early as 2015, it was assessed as being able to miniaturize a nuclear warhead, which would give it the ability to place a usable nuclear weapon atop a long-range missile, thus presenting a profound threat to any country within the missile’s range. In that same year, some analysts concluded that the regime’s KN-08 missile had the range to reach the United States: In other words, North Korea had the potential to attack the U.S. directly with a nuclear weapon. Since then, the government ruled by Kim Jong-un has made every effort to improve its portfolio of nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them.

In 2017, North Korea had two successful tests of a road-mobile ICBM that could reach America. By 2022, the country was testing the Hwasong-17, the world’s largest road-mobile ICBM and likely able to carry three to four nuclear warheads. In January 2023, Kim Jong-un vowed to “exponentially increase” the production of nuclear weapons. In the preceding year, the North Korean military conducted at least 69 ballistic missile tests, eight cruise missile tests, and at least one hypersonic missile test. In addition, from 2014 to 2023, the regime launched numerous missiles with a variety of ranges into the seas around South Korea and Japan and engaged in the most inflammatory diplomatic rhetoric against all powers that it perceived as threatening its viability.

Intermixed, of course, were relentless efforts to attack Western governments and institutions with malware either in the hope of disrupting the normal operations of governments, industry, and private citizens or for more mundane reasons like cyber-theft of intellectual property or to infect computer systems with ransomware so as to extract payment.

Though the actions of these adversaries have differed in their specifics across the years, they generate a common insight: Countries do what they want to do to achieve their objectives regardless of U.S. desires. Each of these threats to U.S. interests has methodically and consistently invested in its military power, expanding capacity, deepening inventories, and improving the modernity of its forces. Each is more capable today than it was 10 years ago.

Russia might be the exception given the losses it has sustained in its 18-month war against Ukraine, but even in this case, there is serious cause for concern. War generates experience and demands adaptation. Those who are not engaged in war adapt from an academic understanding informed by observation, experimentation, simulation, and exercises. Such adaptation lacks urgency and can lead to presumed solutions that fail under the stress of real-world application. In Russia’s case, its losses have been absorbed by its land forces, but they have adapted along the way, even if that has meant reverting to old but proven Soviet practices that emphasize volume of fire, obstacles, and entrenchment over maneuver. Untouched are its submarine force, long-range bombers, and nuclear weapons—the tools that are of greatest concern to the U.S. homeland.

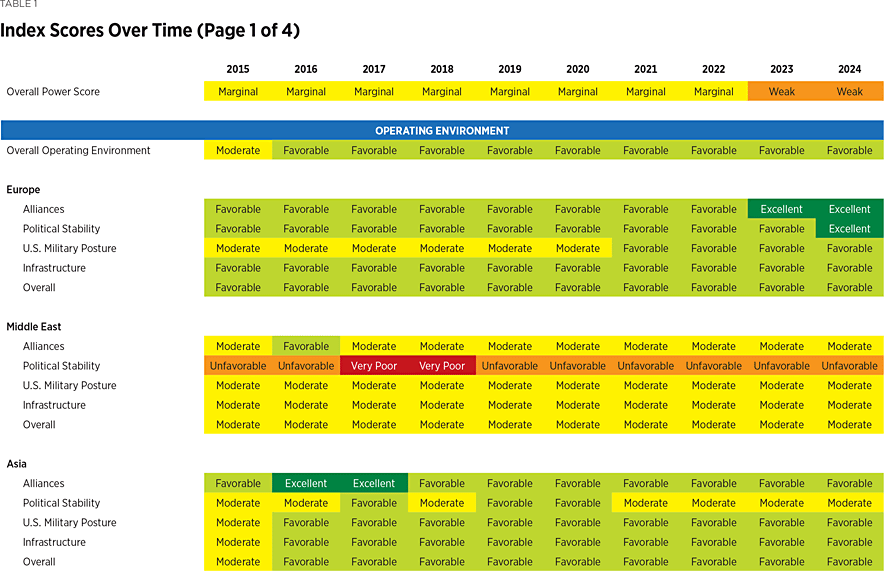

The Operating Environment: Europe

As we have seen, the countries posing the most substantial threats to U.S. interests have improved their position over the past decade. What of U.S. allies and the environment within which America’s military forces would undertake combat operations? The answer is sobering: Unfortunately, our allies have not been as focused and committed as our adversaries have been.

In 2014, only four of NATO’s member countries met the benchmark objective of investing 2 percent of GDP in their national defense and spending 20 percent of that 2 percent on equipment. Germany invested only 1.3 percent, and most of that went to personnel. France and the United Kingdom were reducing their spending on defense: In the U.K., the government proposed to cut defense by 7.5 percent. All member countries were struggling with debt and high unemployment. NATO, as an organization, was struggling to define itself in terms of mission, its purpose for being. The Cold War was long over, and the war on terrorism, initiated by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, had lost its unifying imperative. In 2014, the U.S. had no armored brigades in Europe.

The following years were shaped by high unemployment, national debt crises, nationalism, unchecked migration across Europe from North Africa and the Middle East, and the occasional terrorist attack in a major European city. NATO was plagued by poor readiness within the forces contributed to it by member countries. Perhaps the worst offender was Germany, long the industrial heart of Europe and locked into competition with France to see which country would be most influential within the European Union (EU).

In 2017, Germany could field only two battalions that were deemed combat ready. In 2018, Germany had no working submarines, there were 21,000 vacant positions within its military, and only 95 of its 224 Leopard II main battle tanks were in service. By 2020, the military condition of Germany and the U.K. had worsened, and Turkey had been bounced from the F-35 program because of its purchase of the S-400 air defense system from Russia: The U.S. could not accept having its premier fighter regularly surveilled by a Russian-made air defense radar system.

In 2018, Great Britain left the EU—the much-reported Brexit divorce within Europe. Though Britain retained its status as a NATO member, it was at odds with its European neighbors, leaving Germany and France to “call the shots” in continental affairs. This made Germany’s status as a military power all the more critical.

In 2020, Europe saw a 50 percent increase in Russian activity probing NATO member air and sea spaces, and the COVID lockdown had wreaked havoc on military readiness. Germany’s readiness continued to plummet, especially across its aviation community; France was almost wholly distracted by internal security problems; and the U.S. had stated its intention to withdraw almost all of its forces from Germany, sending some to Poland but bringing most back home.

In 2021, Germany had only 13 tanks available for deployment, half of its military pilots were not NATO-certified, and it was revealed that German warships relied on Russian navigation systems. Great Britain enacted additional defense cuts, and NATO had largely withdrawn from operations in Afghanistan, depriving it of even that combat experience in a war that pitted modern Western forces against poorly equipped Taliban insurgents.

By 2022, NATO acknowledged that Russia posed the most significant challenge to European security—dramatically shown by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that February, although China was a rising threat given its penetration into Europe’s markets, tech sector, and physical infrastructure like ports. With the war raging in Ukraine, NATO organized itself to coordinate support to the embattled country.

While the U.S. reinvested in its presence on the continent, Germany continued to struggle with its modernization plans, and the U.K. was barely able to field a single army division composed of just one armor brigade and one maneuver brigade. The once magnificent British Royal Navy had shrunk to a mere 20 surface combatants: two aircraft carriers, six destroyers, and 12 frigates. In 2023, the entire British military—army, navy, air force, and marine corps—numbered 150,350 personnel,18 smaller than the U.S. Marine Corps alone (currently 174,550). Its army of 79,350 soldiers19 is the smallest Great Britain has fielded since the 1700s.20

In contrast, Poland surged ahead with substantial investments in its military forces, defense industrial base, and purchase of foreign-manufactured military equipment. It also extended an open invitation to the United States to station permanently based forces in the country.

As Poland’s investment in its military rose to 4 percent of GDP and Latvia reintroduced military conscription, Germany was having second thoughts about its 2022 pledge to invest an additional €100 billion in its military.

Finland became the 31st member of NATO in 2023, bringing with it a highly capable defense force but adding its 830-mile border with Russia to NATO’s list of responsibilities. Sweden will also join NATO, although Turkey is slow-rolling the accession process.

Meanwhile, Russia was using more artillery ammunition in two days than existed in the entirety of the U.K.’s stocks21—certainly an alarming reality for most NATO members who had allowed their defense production capabilities to wither since the end of the Cold War.

The Operating Environment: The Middle East

Over the past decade, the Middle East remained what it almost always has been: characterized by religious and political rivalries, terrorism, instability, and competition for influence by the world’s major powers (the U.S., Russia, and China) driven by the global importance of the energy that flows from the region. When the first edition of the Index was published in early 2015, the Syrian civil war had already resulted in nearly 200,000 deaths and the displacement of 9 million refugees, and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) was on the rise. Since that time, ISIS has been defeated in practical terms, but not before laying waste a good portion of Western Iraq and Eastern Syria and generating affiliate terrorist groups in Africa and Central Asia.

The Obama Administration engineered an agreement with Iran in which it was to pause its nuclear program in exchange for the release of $100 billion in frozen assets and relief from some sanctions. (Importantly, the agreement did not require the dismantlement of Iran’s nuclear enrichment capabilities nor any corresponding reduction in its development of ballistic missile capabilities, the means by which it would most likely deliver a nuclear weapon. It was later proven that Iran secretly continued its nuclear program in deeply buried facilities and barred international inspection of known facilities that were meant to ensure compliance.) Upon taking office, the Trump Administration withdrew from this flawed agreement just a few years later. The COVID-19 pandemic played havoc with the economies of countries in the Middle East, just as it did globally, and governments were increasingly feeling the pressure of the explosive growth of their youth cohorts. In 2022, two-thirds of the region’s population was under 30 years old and faced few employment options, educational opportunities, or various government-subsidized services—the makings of domestic problems unless carefully managed in the years ahead.

Nevertheless, from a defense/security point of view, the U.S. enjoyed relatively good relations with the assortment of countries hosting or working with the U.S. military, including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, Qatar, and Oman, thereby ensuring good productive access to this key region and enabling various U.S. operations in Iraq, Syria, and the Persian Gulf area.

The Operating Environment: The Asia-Pacific

The Asia-Pacific region was much the same: restive (but without the level of terrorism and rampant instability found in the Middle East) while affording the U.S. excellent access to basing and strong working relationships with key allies (in this case, Japan and South Korea) but under the overhang of growing security challenges (in this case, China and North Korea). Unlike the Middle East or even Europe, the vast distances of the Indo-Pacific region and the distances between basing and support options and likely scenes of action emphasize the additional challenges accompanying any military action of meaningful size and duration.

The U.S. has enduring interests in the broad expanse of the Indo-Pacific. In 2018, 40 percent of global trade goods moved through the Asia market. Sitting astride shipping routes is the Philippines, with which the U.S. has had strained relations, although things improved in 2018, enabling 261 planned activities involving U.S. and Philippine forces. To the south, the U.S. and Australia worked to enhance bilateral relations, and Australia supported an increase in the U.S. military presence to 1,500 personnel on a rotational training/exercise basis. By 2023, U.S. Marines were training to the full agreed upon force size of 2,500 personnel.

Sadly, in 2021, the U.S. suffered a self-inflicted wound in the precipitous and chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan where U.S. forces had been operating for 20 years, first to exact revenge for the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, deposing the Taliban regime that had been harboring al-Qaeda and its leader Osama bin Laden, and later to support the stand-up of the Afghan military with the responsibility both to protect Afghanistan’s interests and to support America’s by denying use of Afghanistan as a sanctuary by terrorist groups like al-Qaeda.

Whether the U.S. should have fully withdrawn its forces, which had been reduced to just 2,500 by January 2021, is a decision that will be debated for many years. The U.S. contingent had suffered no casualties in the preceding 18 months, and the U.S. presence did enable it to shape Afghan policies and gather intelligence on Iran, Pakistan, and a variety of terrorist groups operating in the region. What is indisputable is that the withdrawal was ordered and executed in a way that resulted in the emergency evacuation of 120,000 people, the deaths of 13 U.S. servicemembers from a suicide bomber, the rout of Afghan security forces by the Taliban, the fall of Afghanistan’s government, and the seizure of power by Taliban leaders. All of this combined to damage U.S. credibility and the perception of U.S. competence.

Whether the Afghan debacle incentivized Russia to invade Ukraine or China to become more aggressive toward Taiwan is hard to know, but perceptions of weakness can prompt people who are inclined to action to take advantage of perceived opportunities. This is at the heart of deterrence: the belief that a competitor can thwart one’s ambitions. This extends to perceptions of military power. The U.S. may say it has the world’s most capable military, but friends and foes also review U.S. acquisition programs, budgets, flight hour programs, ship availability, personnel shortfalls, and munitions inventories. To the extent that America’s allies are militarily weak, it falls to the U.S. military to ensure that the country’s interests are defended.

All of which brings us to the status of the U.S. military and how it has changed over the past decade.

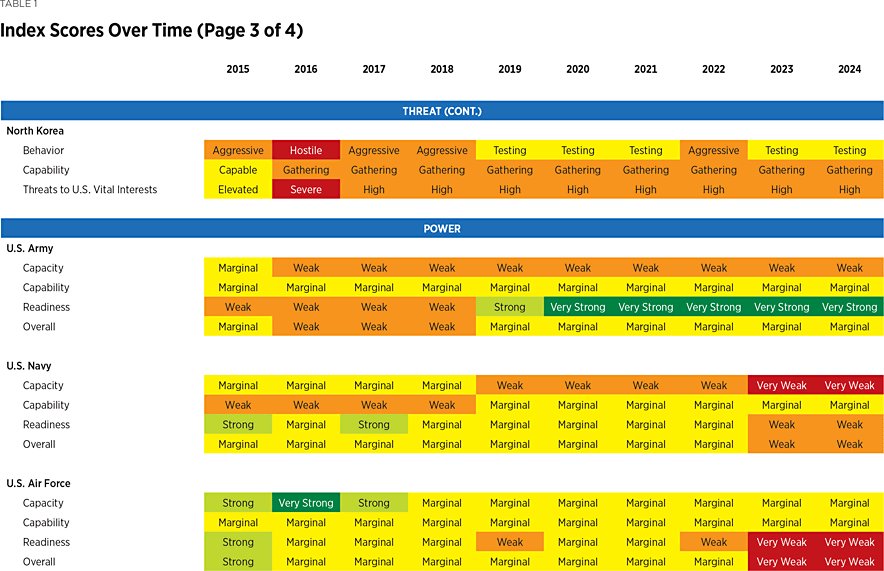

U.S. Military Strength: Evolution or Devolution?

The inaugural 2015 Index addressed the status of the U.S. military in FY 2014 with this summary:

Overall, the Index concludes that the current U.S. military force is adequate to meeting the demands of a single major regional conflict while also attending to various presence and engagement activities…but it would be very hard-pressed to do more and certainly would be ill-equipped to handle two, near-simultaneous major regional contingencies.

The cumulative effect of such factors [as problems with funding, maintenance, and aged equipment] has resulted in a U.S. military that is marginally able to meet the demands of defending America’s vital national interests.22

In general, the services were hobbled with forces that were too small relative to the task of defending U.S. interests in more than one place at a time, and most of the force’s equipment was old: Aircraft averaged nearly 30 years old, more than half of the Navy’s ships were more than 20 years old, and the primary equipment used by the Army and Marine Corps had been purchased in the 1980s or earlier. Service efforts to correct such deficiencies were constrained by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), which arbitrarily capped annual spending on defense and reduced military spending by approximately $1 trillion over a 10-year period.23

The leaders of the services have been consistent over the past 10 years in explaining why new programs were needed and the challenges they faced in recruiting, modernizing, and managing the workload of forces required to deploy repeatedly. But when asked what the impact might be if a requested level of funding wasn’t provided or a procurement program was canceled, they usually answered with something like “Well, Senator, we would have to operate at increased risk” without ever clearly explaining what “risk” meant or what national security interest might be harmed in a specific way.

Within the Index, risk is placed in the context of enduring national security interests and the historical use of military forces to defend those interests in a major conflict. Within this framework, it is easier to see how shortfalls in capacity or forces assessed as not ready for combat can increase the risk to the nation. As already noted, if America’s friends were strong or its enemies were weak, America’s need for a robust military might not be as great, but the 10-year record of reporting shows that both factors are troubling: America’s adversaries continue to gain strength even as its key allies remain troublingly weak militarily. Hence the importance of understanding the status of America’s own military services.

U.S. Army. In 2011, the Army enjoyed an end strength of 566,000 soldiers; in 2013, it fielded 45 Brigade Combat Teams (BCTs). By 2014, its end strength had dropped to 510,000, and the number of BCTs had fallen to 38—a loss of 56,000 soldiers (10 percent of the force and equivalent to two divisions of combat power). Of those 38 BCTs, only two were reported as ready for combat. A year later, end strength had fallen by an additional 20,000 soldiers and a BCT, leaving the Army with only 31, which is where it stands today. In 2017, the Army reported only three BCTs as “ready to fight tonight.”

Over the following years, the service clawed back some readiness. In FY 2023, it reported that 83 percent of the Army was “ready,” although it also reported that BCTs were funded to only 73 percent of training and flying hours for Combat Aviation Brigades were down 13 percent. It seems odd that readiness rates were at their highest in the decade when resources for training and readiness were down, but that’s what the Army has reported.

To address its problem with aging equipment—the M1A2 Abrams main battle tank and M2/M3 Bradley Fighting Vehicle, among others—it has several programs in development, but these will not mature for several years. Meanwhile, its artillery (cannon and rocket) is outranged by every major competitor and most allies. Army procurement accounts were cut by 7 percent in FY 2022, R&D accounts were cut by six percent, and military construction funds fell to a historically low level. Compounding the allocated funding problem was inflation, which resulted in a loss of $74 billion in purchasing power from FY 2019 to the Army’s current budget request for FY 2024.

Perhaps the hardest problem facing the Army is recruiting. American youth have shown little interest in joining the military. In FY 2022, the Army fell 25 percent short of its recruiting objective, failing to recruit 15,000 new soldiers. For FY 2023, the Army requested to have its end strength reduced by 33,000 soldiers, anticipating that it will fall short in new accessions this year as well, leaving it with a force of just 452,000 soldiers—far short of the 540,000 to 550,000 the Chief of Staff of the Army felt was needed in FY 2018. The Army’s plan has been to thicken, or slightly overstaff, its BCTs rather than grow more of them, but these manpower problems will instead result in understaffing.

U.S. Navy. If the Army is struggling to staff its formations and replace its equipment, the Navy is caught in a maelstrom, unable to maintain a consistent, compelling argument for the size and shape of the fleet it should sail and chronically underfunded even for the 30-year shipbuilding program it is currently trying to execute. The poor condition of its shipyards adds to its ship availability woes, including a serious maintenance backlog.

At 297 ships, the Navy is roughly half the size it was near the end of the Cold War, and it has not shown any appreciable ability to change that condition. In FY 2014, the Navy had 282 ships. The number dropped to 271 in FY 2015 and climbed to 300 in FY 2020 before losing steam and falling to its current 297. This is in spite of a sustained argument since FY 2018 for a fleet of 355 manned ships, although the Navy’s plan at that time would not have realized that goal until 2050. The service adjusted its approach to achieve its objective by 2034, but only by planning to extend the life of all of its Arleigh Burke–class destroyers to 45 years or more, a potentially unrealistic goal given that the expected service life of such warships historically has not exceeded 30 years.

During the Cold War, the nearly 600-ship fleet allowed the Navy to maintain approximately 100 ships at sea on a regular basis. The Navy maintains that same level of deployed presence but with a fleet half the size, doubling the workload for sailors and ships, which translates into increased maintenance and repair costs (and resultant delays in returning ships to sea and backlogged maintenance actions for ships needing repair) and a heightened risk of burnout for the force. It is a vicious circle that cannot be broken without dramatic increases in funding that enable more ships to be built and/or a reduced demand for ships to be deployed, which would mean a reduced U.S. naval presence in key regions around the world.

In January 2017, no aircraft carriers were deployed. The U.S. Navy has no dedicated mine countermeasures ships or any frigate-like ships (a role that was supposed to be filled by Littoral Combat Ships that have underperformed relative to expectations and are now being retired far in advance of their planned service life). In 2023, the Commandant of the Marine Corps expressed to Congress his regret that Marine Corps forces were unable to assist with disaster relief operations in Turkey or the evacuation of U.S. citizens from Sudan because there were no amphibious ships available.24 He also made clear both that “there is no plan to get to the minimum requirements [for 31 amphibious ships]” under the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan and that the prospects for commensurate funding within the defense budget were not good.25

In FY 2023, it was not uncommon for ships to be undermanned by 15 percent. U.S. Navy end strength fell by 1,300 sailors; shipyards remained in a poor state of repair; every project to correct such deficiencies was delayed or over budget; and the Navy, given the paucity of resources and the strategic importance of ballistic missile and fast attack submarines, prioritized submarine construction over that of surface ships. Two major ship collisions in 201726 and the loss of a major amphibious assault ship27 due to an incompetently handled fire while pierside in 2020 called into question the U.S. Navy’s ability to get the basics right, to say nothing of its ability to project naval power in support of securing national interests or even to present a compelling case for how it intended to correct this array of problems.

U.S. naval power appears to be in chaos relative to national interests and the otherwise positive impact of naval engagement and deterrent value of a strong naval force, and there are few glimmers of hope for rapid correction in the near future.

U.S. Air Force. If the Army is struggling and the Navy is lost at sea, the Air Force appears to believe that threats to the United States, at least those that would have to be addressed by air power, are not likely to manifest themselves until the 2030s. How else to explain dangerously low readiness among pilots and squadrons and the prioritization of future capabilities over ensuring that the current Air Force is able to field airpower that is relevant to current challenges?

In 2014, 17 of the service’s 40 active-duty, combat-coded squadrons were temporarily shut down because of sequestration (the lopping off of funding imposed by the BCA). By 2015, the Air Force was the oldest (in average age of aircraft) and smallest it had been since becoming an independent service in 1947. The following year, the average pilot flew 150 hours or less, a significant drop from the 200-plus hours Cold War predecessors flew. By FY 2017, there were only 32 squadrons in the Active Component; only 106 F-15Cs (averaging 33 years old); fewer than 100 operationally available F-22s; and a paltry four combat-coded squadrons assessed as fully mission capable.

Conditions got worse in the following years.

By 2018, the average pilot was flying less than twice per week, and the Air Force was short 2,000 pilots. To compensate for this, in 2019, the service began to move pilots from non-flying billets to operational squadrons. Part of the problem with pilot readiness was the availability of aircraft. Limited numbers of aircraft mean limited opportunities for pilots to fly. Knowing this problem, the following year, the service oddly began to invest more in research and development for a next-generation aircraft, which it hoped would be produced in the 2030s, than in procuring greater numbers of F-35s, the only U.S. fifth-generation aircraft already in production. Investing in the latter would ameliorate the trend of the service’s problems with old and unready aircraft and, therefore, its problem with pilot readiness. Instead, the service elected to spend more on future aircraft that will not be available until the late 2030s.

2018 was also the year that the service released its massive study reporting on its deep analysis of how much airpower the country needed to secure national interests. “The Air Force We Need” (TAFWN) called for a larger force and for pilots to fly more to be more proficient. This would mean a larger budget. The Trump Administration supported this, increasing the Air Force budget 31 percent over the FY 2017–FY 2021 years. In spite of this, U.S. Air Force procurement of aircraft remained flat while research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) more than doubled. In spite of current need as documented by the Air Force itself, the service invested in the future to have a capability that might take 10 years or more to realize rather than addressing its current problems.

In FY 2022, procurement shrank an additional 10 percent, dropping from $28.4 billion to $25.6 billion, while RDT&E climbed to 70 percent more than procurement. The number of readily available combat-coded fighters dropped to 885, the average age of all aircraft rose to 29.4 years, and the average fighter pilot flew only 2.5 hours per week. This translates into an embarrassing 129 hours per year, which is significantly less than the number needed to obtain, much less maintain, combat proficiency. According to the Air Force’s FY 2024 budget documents, funding for flying supported 1.07 million flying hours, 8 percent less than was funded during the locust years of sequestration. But the service has shown itself unable to fly even those hours. In 2022, the service failed to fly 23,000 hours because it funded (and continues to fund) just 85 percent of the spare parts needed to fly the 1.12 million flying hours funded in that year.

If it adheres to its current trajectory, the Air Force will reduce its fleet by almost 25 percent over the next five years. Alarmingly, the average age of aircraft has risen to 30 years; F-15Cs are now at 38 years; the KC-135 refueling fleet averages more than 60 years; and the service’s replacement refueler, the KC-46, continues to be plagued by technical problems, which means 23 percent of the fleet will be unavailable until the late 2030s.

As currently postured, the Air Force’s fleet of air superiority fighters is one-fifth the size of its Cold War ancestor: 81 operationally available F-22s compared to 400 F-15Cs. And the service is still short 650 pilots.

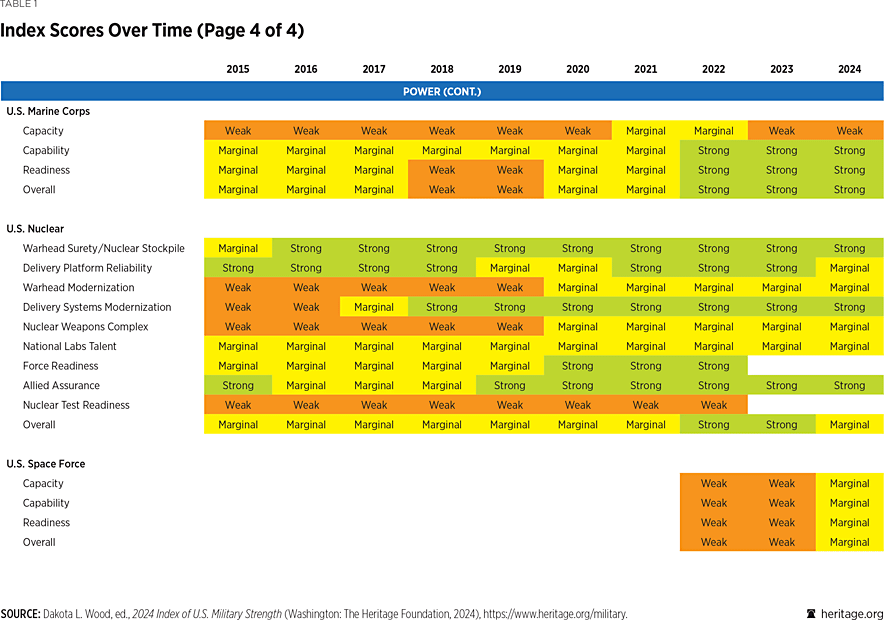

U.S. Marine Corps. Of the services, the Marine Corps appears to have the firmest grasp of what it needs to be and what it needs to do to be prepared for war. Though generating controversy within its retired community, the Corps’ Force Design 2030 (FD 2030) project has established a rationale and objectives for substantial change across the service driven by changes in the threat environment, the evolution of combat-relevant technologies, and a determination to return to the Corps’ primary mission: projecting combat power via the sea. Since the publication of FD 2030 in early 2020, the Corps has aggressively implemented changes that have included the introduction of unmanned air and ground systems; long-range missiles to target ground, air, and sea-based platforms; and new information-sharing tools. Adjustments in its aviation inventory have reduced the numbers of some aircraft like attack helicopters in favor of higher-end drones for surveillance and targeting, and the Corps’ combat formations (most notably the infantry battalion’s size, configuration, and capabilities) are being reviewed and reorganized.

The Corps’ air arm is almost completely modernized—its attack helicopters replaced, a new heavy lift helicopter soon to make its debut, the old CH-46 helicopter replaced by the MV-22 Osprey, and the F-35 quickly replacing the Corps’ inventory of 1980s-design AV-8B Harriers and F/A-18 Hornets. With the Corps having retired its entire inventory of tanks, the age of its ground equipment is shaped by its 1970s-vintage amphibious assault vehicles (AAV-P7, though they have been iteratively updated over the years), which have been restricted from water operations but are still useful on land; its light armored vehicle (LAV, also rather old, having been introduced in the early 1980s); and the acquisition of the amphibious combat vehicle (ACV), initially a placeholder replacement for the AAV but increasingly likely to be a primary combat vehicle for the service. Primary weapon systems for its ground force have been comprehensively updated from small arms and anti-armor weapons to artillery (cannon and rocket) and anti-air missiles. The Corps is also adding an anti-ship missile.

However, the Corps remains too small, even to be the one-war force it accepts as its role. In FY 2012, at the end of sustained operations in Iraq and the continuing mission in Afghanistan, the Corps numbered 202,000 Marines. In FY 2014, end strength and number of units began to fall: 189,000 Marines and 25 battalions in FY 2014; 184,000 in FY 2015 and FY 2016 with 23 battalions; and 177,249 Marines and 22 battalions in FY 2022.

If the Corps does indeed execute distributed, low-signature, reduced logistical demand operations with smaller units composed of slightly older, more experienced Marines, it will still need capacity to be able to sustain operations when attrition is a factor or even to compensate for lengthy operational employment close to enemy forces.

U.S. Space Force. In 2019, the Trump Administration, with the support of Congress, established the U.S. Space Force (USSF). All Department of Defense space capabilities, functions, support, and personnel were transferred from the Air Force, Army, and Navy and consolidated within the new service. By all accounts, the transfer of responsibilities, control of space assets—terrestrial (ground stations) and space-based (satellites)—and service to customers (for example, the geographic combatant commands) went well. The USSF’s challenges come in the form of aging satellites and, akin to its sister services, a shortfall in capacity.

The plethora of space-based systems that constitute America’s ability to leverage the domain have uniformly performed their functions well beyond planned service life, but there does come a point where a satellite must be replaced, and this is where U.S. space programs fall short: the timeliness of bringing new systems into service. Fortunately, the Space Development Agency, which was recently absorbed into the Space Force, has begun to field satellites at an accelerated pace, adding 23 tracking and communications satellites in the past year alone. The commercial space sector also has advanced at a remarkable pace and now launches the majority of missions for the U.S. government, but there are some functions that should remain within the control of the government, and it is in this area that concerns are mounting.

While the U.S. is still outpacing China and Russia in launches, China is gaining. In FY 2023, the U.S. launched 118 missions, China launched 24, and Russia sent 18 packages into orbit. But what these competitors say they are going to do and what they end up executing can be much different. For example, in FY 2022, China announced that it would undertake 22 launches but actually made 62.

Demand for space-based capabilities is growing at a pace that the USSF cannot currently match. Not surprisingly, the U.S. government is increasing its contracts with commercial providers to make up the difference, but the Space Force needs more assets, more people, and more funding if it is to execute its important mission properly.

U.S. Nuclear Portfolio. Age and capacity are common themes across defense entities, and this is certainly the case with respect to America’s nuclear establishment and portfolio of capabilities. In particular, the infrastructure that undergirds all nuclear efforts is quite old, as is the collection of people who constitute expertise in this field.

In FY 2014, nuclear modernization programs were moribund. There was a broad consensus that the viability of America’s nuclear deterrent depended on assurances that the various components would work as intended when needed. This included the weapons themselves; delivery vehicles (aircraft and missiles); testing apparatus; manufacturing facilities; and the pool of people with the required expertise. The areas of understanding and technical assurance began to generate doubts within a little more than a decade after the U.S. self-imposed a moratorium on yield-producing experiments.

“[I]n the past,” according to the late Major General Robert Smolen, some of the nuclear weapon problems that the U.S. now faces “would have [been] resolved with nuclear tests.” By 2005, a consensus emerged in the NNSA, informed by the nuclear weapons labs, that it would “be increasingly difficult and risky to attempt to replicate exactly existing warheads without nuclear testing and that creating a reliable replacement warhead should be explored.” When the U.S. did conduct nuclear tests, it frequently found that small changes in a weapon’s tested configuration had a dramatic impact on weapons performance. In fact, the 1958–1961 testing moratorium resulted in weapons with serious problems being introduced into the U.S. stockpile.28

The U.S. has not conducted a yield- producing experiment since 1992. In 2018, the Trump Administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) recognized that China and Russia were actively exploring new weapon designs—something the U.S. was not doing. In 2020, the nuclear establishment was required to be able to conduct a nuclear test within 24 to 36 months of being tasked with doing so. However, the continued deterioration of technical and diagnostic equipment and the inability of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to fill technical positions created substantial doubt that this could be done. At that point, more than 40 percent of the workforce was eligible for retirement over the next five years, highlighting the talent-management problem within the nuclear enterprise.

The 2022 Index reported on the problematic nature of a tripolar world. China was working to expand its nuclear weapons capacity to more than twice its current size by the end of the decade. Russia was consistently violating various non-proliferation and nuclear arms reduction treaties and was committed to developing new designs for weapons at all levels of use: tactical, operational, and strategic. Against the backdrop of China’s and Russia’s aggressive modernization, the U.S. was mired in policy debates, self-imposed restraints, inadequate funding, and a persistent degradation of facilities, talent, and production capabilities throughout the nuclear establishment.

By 2023, Russia had ended any pretense of adhering to New START, formally suspending its commitment to the treaty. China was now known to be tripling its ICBM launch capacity. Some reports had emerged that Iran was enriching uranium to 83.7 percent purity (just shy of the 90 percent needed for a weapon) and probably had enough fissile material for at least one bomb.29 Happily, Congress was continuing a few years of strong support for U.S. nuclear modernization; whether that continues remains to be seen.

At present, nuclear options are too limited, the U.S. nuclear knowledge base is increasingly theoretical and academic rather than drawn from experience, and the workforce continues to age. Although the various components are relatively healthy at present—delivery vehicles, exercises and testing, a few modernization programs underway, and renewed interest in both the executive and legislative branches—there is no margin for delay or error when it comes to the viability and assuredness of America’s nuclear weapons portfolio.

Missile Defense. “By successive choices of post–Cold War Administrations and Congresses,” the 2019 Index reported, “the United States does not have in place a comprehensive ballistic missile defense system that would be capable of defending the homeland and allies from ballistic missile threats.” Instead, “U.S. efforts have focused on a limited architecture protecting the homeland and on deploying and advancing regional missile defense systems.”30

In 2018, America’s missile defense capability was beset by limited investment, canceled programs, and limited capacity to handle multiple targets and was mostly focused on a very limited threat from one direction (North Korea) and perhaps a limited strike from China.31 The U.S. possessed no ability to intercept a missile in its boost phase and still has no such ability in 2023. Funding, a reflection of policy and interest, has been volatile and inconsistent, varying from one year to the next and subject to change.

By 2021, China, Russia, and North Korea were investing in multiple independently targeted reentry vehicle (MIRV) options, cruise missiles equipped with nuclear warheads, advanced decoys, and countermeasures that make a successful intercept more complicated. The more advanced competitors—China and Russia—were also making progress with hypersonic glide vehicle programs.

In March 2023, General Glen VanHerck, Commander, U.S. Northern Command and North American Aerospace Defense Command, testified that North Korea had “tested at least 65 conventional theater and long-range nuclear capabilities over the last year.” Iran tested a 2,000-kilometer ballistic missile and displayed what was advertised as a hypersonic missile. In 2021, China was known to have tested a fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS) that included a deployable hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV), enabling China to launch the weapon into space and keep it in low earth orbit until ready for a de-orbital maneuver to use the maneuverable HGV to attack a target.32 Lacking any predictable trajectory as would be the case with a conventional ballistic missile, an HGV makes intercepting the weapon extremely difficult.

Efforts are being made to improve the U.S. missile defense posture at locations in Europe, Guam, and Alaska, but such efforts appear to lack a sense of urgency and robustness. They certainly do not match the pace at which adversaries are improving their ability to threaten the U.S. and its interests.

Conclusion: A Pattern of Substantial Erosion

The upshot to all of this—the trends seen across all of the military services and critical enablers like missile defense and the strategic deterrent provided by nuclear weapons—is that U.S. military strength has substantially eroded over the past decade.

- All elements have shrunk in capacity,

- Nearly all platform-based capabilities have grown older, and

- Most functional components have become less ready.

Where the United States would have been able to engage Soviet forces on a global scale in the 1980s, the current U.S. military would be hard-pressed to handle a single major conflict. To repeat an earlier point, if U.S. allies were strong, ready, and competent, shortfalls in the American military portfolio might not be so worrisome; the same would be true if America’s competitors were weak or less aggressive. But on both counts—among both allies and competitors—trends do not favor U.S. interests and make the military’s weakened state all the more alarming.

If the U.S. is to protect its interests, it must have a military that is large enough, modern enough, and ready enough to be equal to the task and relevant to the nature of the world as it is today, not 10 or 20 years from now. If the U.S. is to shape world affairs to suit its interests instead of merely reacting to significant changes, thus ceding initiative and opportunity to opponents, it must possess the means to deter bad behavior, reassure friends and allies, and defeat enemies that actively threaten the U.S. homeland, Americans abroad, and America’s economic, political, and security interests in regions that are key to its future.

At present, the condition of the U.S. military introduces substantial risk in all of these areas.

As is true of any other crisis—an automobile accident, storm damage, or a medical emergency—the time, place, and severity of war cannot be predicted, but we know they happen. The prudent person prepares for such eventualities by investing in insurance, adopting healthy and safe practices, or stockpiling to mitigate the consequences of a significant disruption. Throughout its history, the U.S. has found itself at war about every 15 to 20 years: The record is indisputable. Wars can occur because of policy decisions (wars of choice) or because they are forced on the U.S. by, for example, threats to key interests or by treaty obligations (wars of necessity). In either case, either the country is ready or it isn’t.

At present, the country is not ready, at least not to the extent that it might mitigate the profound costs of a large war. Weakness may be provocative as well, tempting would-be aggressors to take actions or to accept risks from which they might otherwise have been deterred.

Ten years of assessing the deteriorating condition of the U.S. military reveals that short-term political interests almost always displace sustained annual and key long-term investments that are essential to ensuring the viability and effectiveness of military power. This is true not just for the U.S., but even more so for important allies who have allowed their military establishments to decline to dangerous states of unreadiness. Sometimes, a quick injection of attention or funding can result in rapid, positive change, but this is not the case when it comes to military strength. It takes years to build a ship, to recruit and train a soldier, to have pilots who are competent in aerial battle against a capable enemy, and to have larger formations that are effective in joint and combined operations undertaken far from home and that include battle in all domains. When war does happen, desired forces that should be in place a decade in the future are irrelevant. What matters is what the U.S. has at hand in the moment of danger.

The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength has methodically and meticulously tracked and reported the declining state of America’s military establishment for a decade. We hope that senior leaders in our government and the American people will take notice and take action to correct this trend and ensure the best possible future both for the American people and for the free world at large.

Appendix: The Index of U.S. Military Strength, 2015–2024

- 2015 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2015), http://ims-2015.s3.amazonaws.com/2015_Index_of_US_Military_Strength_FINAL.pdf.

- 2016 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2015), https://s3.amazonaws.com/ims-2016/PDF/2016_Index_of_US_Military_Strength_FULL.pdf.

- 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2016), http://ims-2017.s3.amazonaws.com/2017_Index_of_Military_Strength_WEB.pdf.

- 2018 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2018), https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/2018_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength-2.pdf.

- 2019 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2019), https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/2019_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength_WEB.pdf.

- 2020 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2020), https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/2020_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength_WEB.pdf.

- 2021 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2021), https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/2021_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength_WEB_0.pdf.

- 2022 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2022), https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/2022_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength.pdf.

- 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2023), http://static.heritage.org/2022/Military_Index/2023_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength.pdf.

- 2024 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2024).

Endnotes

[1] The U.S. possesses 274 cargo aircraft capable of long-range heavy lift. Other countries that possess a similar ability include the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, among others but in limited numbers. The U.S. inventory of long-range heavy lift cargo aircraft is 10 times that of any ally or partner nation. European countries most often fly the A400M, a turbo-prop cargo aircraft with a range of 2,000 miles, roughly comparable to the U.S. C-17, a jet-powered cargo aircraft but with one-quarter the payload. Russia and China possess 125 and 70 heavy lift aircraft, respectively. U.S. inventory taken from 2023 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2023), p. 403, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/2023_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength.pdf. All other quantities taken from International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2023: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics (London: Routledge, 2023), pp. 191 (Russia) and 243 (China), p. 243, https://www.iiss.org/contentassets/2209ee34637145989abcaed66e35967d/mb2023-book.pdf (accessed September 10, 2023).

[2] Sébastien Roblin, “As Losses Mount, Russia Is Reactivating Soviet-Era T-54 Tanks. That Says So Much,” Popular Mechanics, March 24, 2023, https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a43392278/russia-reactivating-t54-tanks-ukraine/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[3] Jeff Schogol, “Russia Is Hammering Ukraine with up to 60,000 Artillery Shells and Rockets Every Day,” Task & Purpose, June 13, 2022, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/russia-artillery-rocket-strikes-east-ukraine/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[4] Associated Press and ABC [Australian Broadcasting Corporation] News, “Why the Hard-Hitting 155mm Howitzer Is Crucial to Ukraine’s Struggle Against Russian Invasion,” April 25, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-04-26/155-mm-howitzer-round-ukraine-war/102263322 (accessed September 10, 2023).

[5] A statement often attributed to Joseph Stalin, although this is disputable.

[6] See Appendix, “The Index of U.S. Military Strength, 2015–2024,” infra. The appendix includes links to all previous editions of the Index. Because all are available in readily accessible pdf format, and because including citations for every reference drawn from the 10 years of the Index would add unnecessarily to the length of this essay, we have elected (except for quoted material) to include citations only for non-Index sources that might not be as familiar to the general reader.

[7] Shannon Collins, “Desert Storm: A Look Back,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 11, 2019, https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/1728715/desert-storm-a-look-back/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[8] Serena Seyfort, “Explainer: What Are China’s ‘Artificial Islands’ and Why Are There Concerns About Them,” 9News [Australia], November 26, 2021, https://www.9news.com.au/world/what-are-chinas-artificial-islands-in-the-south-china-sea-and-why-are-there-concerns-about-them/3f0d47ab-1b3a-4a8a-bfc6-7350c5267308 (accessed September 10, 2023).

[9] Reuters, “China Formally Opens First Overseas Military Base in Djibouti,” August 1, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-djibouti-idUSKBN1AH3E3 (accessed September 10, 2023).

[10] Bloomberg, “Explainer: What Is the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and Why Is It Important?” gCaptain, July 26, 2018, https://gcaptain.com/explainer-what-is-the-bab-el-mandeb-strait-and-why-is-it-important/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[11] The Chinese now have more J-20s than the U.S. has F-22s, and their production line is expected to deliver 120 J-20s in 2023, more than twice the number of F-35s the U.S. Air Force will acquire this year. See Editorial Staff, “China’s Air Force Surges J-20 Stealth Fighter Acquisitions to 120+ Annually: USAF Receiving Just 48 F-35s,” Military Watch Magazine, July 20, 2023, https://militarywatchmagazine.com/article/china-surge-j20-120-f35s-48 (accessed September 13, 2023).

[12] Stuart Greer and Mykhaylo Shtekel, “Ukraine’s Navy: A Tale of Betrayal, Loyalty, and Revival,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Ukrainian Service, April 27, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/sea-change-reviving-ukraine-s-navy/30579196.html (accessed September 10, 2023). See commentary at the 4:20 mark.

[13] The U.S. possesses two heavy icebreakers, the Polar Star and the Polar Sea (heavy meaning the ability to crunch through the very thick ice found in the Arctic and Antarctic regions). Both ships are nearly 50 years old and routinely suffer mechanical problems. The Polar Sea being the worse of the two, it is used for spare parts to keep the Polar Star operational. See Kyle Mizokami, “The U.S.’s Icebreaker Fleet Is Finally Getting Some Much-Needed Attention,” Popular Mechanics, June 12, 2020, https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/navy-ships/a32841298/white-house-orders-review-of-us-icebreaker-fleet-capabilities/ (accessed October 19, 2023).

[14] Guy Faulconbridge, “Russia Produces First Set of Poseidon Super Torpedoes—TASS,” Reuters, January 16, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-produces-first-nuclear-warheads-poseidon-super-torpedo-tass-2023-01-16/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[15] Reuben Johnson, “NATO’s Big Concern from Russia’s ZAPAD Exercise: Putin’s Forces Lingering in Belarus,” Breaking Defense, October 4, 2021, https://breakingdefense.com/2021/10/biggest-takeaway-from-russias-zapad-exercise-putins-forces-linger-in-belarus/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[16] At the time of this writing, the war was in its early stages with no clear end state in sight. Israel’s response with military strikes into Gaza and laying siege to the coastal entity necessarily resulted in casualties (military and civilian) and the destruction of a great amount of infrastructure. In turn, Gazans, their fellow Palestinians in the West Bank and elsewhere, supporters of the Palestinians worldwide, and enemies of Israel writ large have staged large protests calling for additional attacks on Israel. Iran, Hezbollah, and a number of related groups have moved to act against the Israelis, with Hezbollah and as yet unidentified entities in Syria firing rockets against targets in Israel and engaging Israeli troops in some as yet minor skirmishes. For a rolling timeline of this conflict in the Middle East, see Jessica Murphy and Marianna Brady, “Hundreds Feared Dead at Gaza Hospital as Israel Denies Strike,” BBC News, October 18, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/live/world-middle-east-67119233 (accessed October 19, 2023).

[17] Francois Murphy, “Iran Expands Stock of Near-Weapons Grade Uranium, IAEA Reports No Progress,” Reuters, September 4, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iaea-reports-no-progress-iran-uranium-stock-enriched-60-grows-2023-09-04/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[18] International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2023, p. 145.

[19] Ibid., p. 145.

[20] Dean Michael, “The Size and Strength of the British Army,” Daysack Media, https://daysackmedia.co.uk/resources/the-size-of-the-british-army/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[21] Daniel Michaels and Alistair MacDonald, “EU Pledges to Spend Over $1 Billion on Arms for Ukraine, Member States,” The Wall Street Journal, March 8, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/eu-pledges-to-spend-over-1-billion-on-arms-for-ukraine-member-states-b35aa3d (accessed September 10, 2023).

[22] 2015 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2015), p. 14, http://ims-2015.s3.amazonaws.com/2015_Index_of_US_Military_Strength_FINAL.pdf (accessed September 10, 2023).

[23] Todd Harrison, “What Has the Budget Control Act of 2011 Meant for Defense?” Center for Strategic and International Studies Critical Questions, August 1, 2016, https://www.csis.org/analysis/what-has-budget-control-act-2011-meant-defense (accessed September 10, 2023).

[24] Konstantin Toropin, “‘I Let Down the Combatant Commander’: Marine Leader Regrets His Forces Weren’t Available for Recent Crises,” Military.com, April 28, 2023, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2023/04/28/top-marine-general-felt-he-let-down-commanders-lack-of-marines-available-emergencies.html (accessed September 10, 2023).

[25] Sam LaGrone, “CMC Berger to Senate: ‘There’s No Plan’ to Meet Amphib Warship Requirements,” U.S. Naval Institute News, March 28, 2023, https://news.usni.org/2023/03/28/cmc-berger-to-senate-theres-no-plan-to-meet-amphib-warship-requirements (accessed September 10, 2023).

[26] Diana Stancy Correll, “After McCain, Fitzgerald Collision Reports, Navy Says It’s Focused on ‘Fundamentals’ of Warfighting,” Navy Times, July 1, 2021, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2021/07/01/after-mccain-fitzgerald-collision-reports-navy-says-its-focused-on-fundamentals-of-warfighting/ (accessed September 10, 2023).

[27] Lolita C. Baldor, “Navy Probe Finds Major Failures in San Diego Fire That Destroyed Ship,” Los Angeles Times, October 19, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-10-19/navy-probe-major-failures-san-diego-fire-destroyed-ship (accessed September 10, 2023).

[28] 2018 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2018), p. 383, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/2018_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength-2.pdf.

[29] Bethany Bell and David Gritten, “Iran Nuclear: IAEA Inspectors Find Uranium Particles Enriched to 83.7%,” BBC News, March 1, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-64810145 (accessed September 10, 2023).

[30] 2019 Index of U.S. Military Strength, ed. Dakota L. Wood (Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2019), p. 451, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/2019_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength_WEB.pdf (accessed September 10, 2023).

[31] The U.S. has maintained a regional missile defense system in Romania since 2016. Derived from the Navy’s Aegis Weapon System and known as Aegis Ashore, it uses the AN/SPY-1 radar, Mark 41 Vertical Launching System (VLS), and Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) interceptors. An Aegis Ashore system has also been installed in Poland and is expected to be operational by the end of calendar year 2023. Both systems are intended primarily to intercept missiles fired from Iran. See Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service Report for Members and Committees of Congress No. RL33745, updated August 28, 2023, p. 7, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33745 (accessed October 19, 2023), and Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance, “Poland,” September 22, 2023, https://missiledefenseadvocacy.org/intl_cooperation/poland/ (accessed October 19, 2023).

[32] Theresa Hitchens, “It’s a FOBS, Space Force’s Saltzman Confirms amid Chinese Weapons Test Confusion,” Breaking Defense, November 29, 2021, https://breakingdefense.com/2021/11/its-a-fobs-space-forces-saltzman-confirms-amid-chinese-weapons-test-confusion/ (accessed September 10, 2023).