The Declaration of Independence, along with the preamble of the Constitution and speeches and writings of our statesmen, help define the foundational character and values of America. The Declaration’s most recognizable phrase—“all men are created equal”—is a standard to which we can hold both ourselves and our country.

What does equality mean? Of course, people aren’t equal in their attributes. Some are tall, others short; some rich, others poor; some smart, others not. But all are equal in the two most important ways: We are all endowed by God with the same unalienable rights, and no one is born with the privilege to rule over other people without their consent.2 Thomas Jefferson said that “the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of god.”3 “Men” in the Declaration is a substitute for “mankind” and includes everyone, no matter what they look like. Men and women can have different physical features, minds, and ethnicities, but none of those differences undermines their fundamental equality as human beings who have the right to govern themselves and to be governed only with their consent.

The Declaration did not describe current conditions. Sadly, America fell short of the promise of human equality because the states permitted slavery.

“[The Founders] said that man was entitled to be free, because he was endowed by his Creator with that right…. They contended for no class, no condition. They contended for humanity.”4 —John P. Hale

But the existence of slavery did not mean that the principle of human equality was false. In fact, it is precisely because it is true that we know slavery is wrong. The Declaration was one of the standards that told the people they were not being good.

Defenders of slavery argued that the writers of the Declaration did not mean all mankind, but only white people. They were wrong, as John Hale and Abraham Lincoln explained. Lincoln saw that the line “all men are created equal” had “no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain.”5 Why then was it included in the document that declared that separation? Because the document also defined the character of the new nation. The line was included “for future use,” Lincoln said, as a “stumbling block” to slavery and the seed of its future destruction.6

Which is exactly what it turned out to be. That principle of absolute equality became the battle hymn of the Union during the Civil War: “As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.”7 And hundreds of thousands did. At the price of “immeasurable human suffering,” the nation paid for the principle that “all men are created equal, are equal citizens, and must be treated equally before the law.”8

Lincoln’s great observation was that the struggle for absolute equality is never over. He said that the principle of absolute equality must be “constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated.”9 We are always tempted to deny other people their fundamental equality out of hatred, ignorance, or a desire for personal gain. The Declaration, therefore, is our nation’s compass, always pointing to what is right.

The Declaration and the Constitution

What is the relationship between the Declaration and the Constitution? Abraham Lincoln said that the Declaration of Independence was “an ‘apple of gold’ to us. The Union, and the Constitution, are the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it. The picture was made, not to conceal, or destroy the apple; but to adorn, and preserve it.”10 Lincoln is quoting from the Old Testament Book of Proverbs, which says that a good word (truth, praise, or advice) is like a golden apple in a silver frame—something beautiful to be displayed and treasured. Lincoln is saying that the Declaration’s principle of human equality is one such treasure and that the Constitution is the way we preserve and display it. The Declaration gives the Constitution purpose. Equality cannot be supported without institutions that are made to protect it, and the Constitution creates institutions that can do just that.

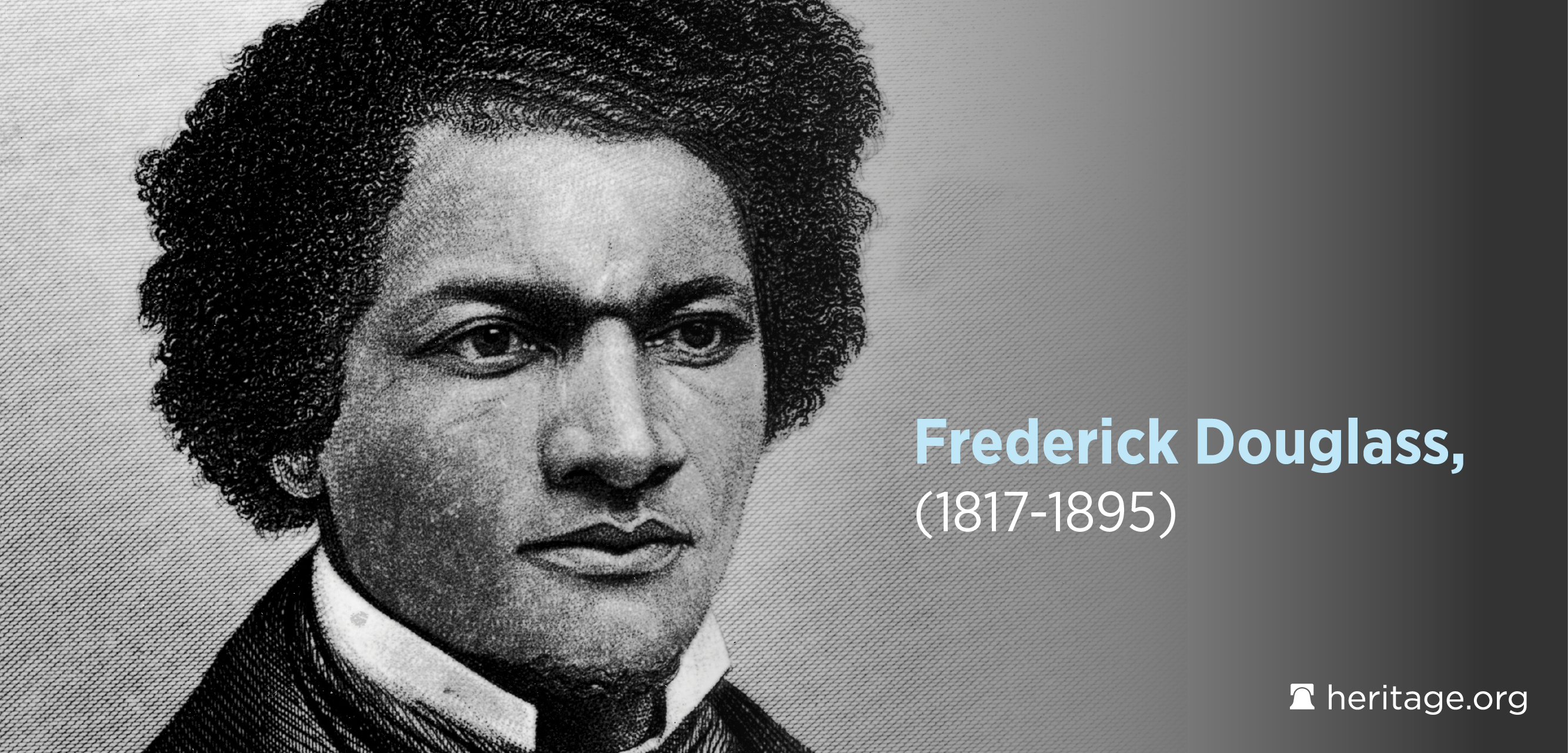

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (1817-1895) was an abolitionist, orator, and statesman—but before that, he had been a slave.

He knew better than anyone else the extent to which the country had fallen short of the Declaration’s principle of absolute equality. Until he escaped to freedom, he had neither liberty nor equality. What he had instead was firsthand knowledge of injustice and scars on his back to remind him of it. Frederick Douglass hated this injustice, but he loved both the Declaration and the Constitution.

Through his studies of human nature and history, he came to believe that those documents offered the best hope of stamping out both slavery and racial discrimination.

ENDNOTES:

2. See Matthew Spalding, We Still Hold These Truths 42–44 (2009).

3. Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Roger Weightman, June 24, 1826.

4. Cong. Globe, 35th Cong., 1st Sess. 344 (1858) (statement of Rep. John P. Hale).

5. Abraham Lincoln, Reply to the Dred Scott decision, June 26, 1857.

6. Id.

7. Julia Ward Howe, Battle Hymn of the Republic, THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY, Feb. 1862.

8. Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, 143 S. Ct. 2141, 2208 (2023) (Thomas, J., concurring).

9. Abraham Lincoln, Reply to the Dred Scott decision, supra note 5.

10. Abraham Lincoln, Fragment on the Constitution and Union, Jan. 1861 (quoting Proverbs 25:11 (“A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in pictures of silver.”)).