“Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.”106 —Chief Justice John Roberts

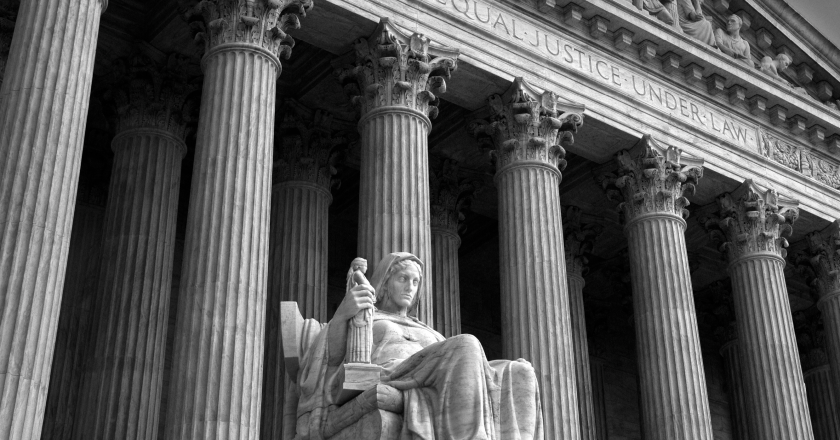

State and federal civil rights acts have forbidden racial and ethnic discrimination in most places, but it still happens, and sometimes the Supreme Court tolerates and even requires it. When and why does the Court do this?

The answers depend on whether a private party or a government entity is discriminating. When the discriminator is a private party, the Supreme Court permits some discrimination. When the discriminator is a government entity (for example, a public school, a state government, or a federal agency), the Supreme Court is stricter.

Discrimination in the Workplace

For example, in the case of private employers, the Supreme Court not only permits some racial discrimination, but may even require it. Two cases created these exceptions to the rule against discrimination: Griggs v. Duke Power107 and United Steelworkers v. Weber.108 In Griggs, the Court created a theory of discrimination called “disparate impact.” Under this theory, intent does not matter. An employer can be liable for discrimination if its job qualifications result in racial disparities. In that case, Duke Power offered manual laborers without high school diplomas the opportunity to work in higher-paying departments if they passed a standardized test. White applicants tended to do better on that test than black applicants did. This was not Duke Power’s doing or its intent, but the Court still held that the test was discriminatory. After Griggs, employers risked getting sued over disparities if they did not racially balance their employees.

Not surprisingly, employers started to do just that, and in Weber, the Supreme Court permitted it. In that case, Brian Weber’s employer created a promotion training program for its employees based on their seniority but with a preference for black employees. Weber was passed over for the program by less senior black employees simply because he was white. The Supreme Court said that this was fine because the civil rights acts are not really universal. Yes, the plain text protects every individual from discrimination “because of such individual’s race,”109 but really, the Court insisted, the acts were meant to give black people special treatment.110 Thus, employers could give black employees preferential treatment at others’ expense.

Making Amends

What explained this retreat from the universal language of the civil rights movement and the civil rights acts? Griggs and Weber arrived about 20 years after Brown v. Board of Education at a time when the “old” civil rights movement had fallen out of favor with intellectuals. They agreed with the black radicals and thought that discrimination should not be eliminated but should instead be turned around to help members of groups once hurt by it.

The Court was never willing, however, to give governments quite as much leeway as it allowed to private parties. With respect to governments, it has adopted the view of Reconstruction Republicans that the law should know “no race, no color, no religion, no nationality, except to prevent distinctions on any of these grounds.”111 Governments may treat people differently based on race only to remedy the effects of its own past racial discrimination.112 For example, after the government put Japanese Americans in internment camps, it was right for it to make amends to those people.

But the Court limits race-based remedies. The government cannot use racial preferences to try to fix vague lingering effects of historical discrimination.113 The reason that the Court requires such specific proof of cause and effect is that without it, governments could point to vague historical harms as a pretext for picking racial favorites.

Discrimination in Higher Education

It used to be the case that one type of government (and government-funded) entity could pick racial favorites. For many years, the Supreme Court said that it would allow universities to discriminate for and against applicants on the basis of race because it trusted universities when they said that racial balancing is good for education.114 As in times past, the Court permitted racial discrimination when experts thought it was a positive good. However, time proved that the Court’s trust was misplaced.

In Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard,115 the Court reversed course. Harvard and the University of North Carolina wanted racially balanced student bodies but found that members of certain races, especially Asians, tended to have much higher academic credentials than members of other races. On academic merit, Asian Americans earned more spots at the schools than the schools wanted them to have. So both institutions made race a critical factor in all stages of the admissions process. They lowered academic standards for people of some races, used stereotypes about racial groups to deny others, and in other ways made race the “determinative” factor for many applicants.116 Harvard and UNC assured the Court that this was for the good of their student bodies, but the Court was no longer willing to trust experts who said that discrimination could be a positive good.

“Anyone who today thinks that some form of racial discrimination will prove ‘helpful’ should thus tread cautiously, lest racial discriminators succeed (as they once did) in using such language to disguise more invidious motives.”117 —Justice Clarence Thomas

As the Court reminded the universities, the “core purpose” of the Equal Protection Clause is “doing away with all governmentally imposed discrimination based on race,” and a “student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.”118

In recent years, the tide of case law has surged toward equality, but it has not yet washed away all the old decisions like Griggs and Weber. Thus, in some contexts, whether the law upholds the colorblind principle remains unclear.

TIMELINE: Major Race-Related Cases at the Supreme Court

ENDNOTES:

106. Students for Fair Admissions, 143 S. Ct. at 2161.

107. 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

108. 443 U.S. 193 (1979).

109. Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII §703(a)(a).

110. 443 U.S. 193, 202 (claiming that the Civil Rights Act was enacted for “the plight of the Negro in our economy”).

111. 3 Cong. Rec. 945 (1875) (statement of Rep. John Lynch).

112. City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989).

113. Id.

114. See, e.g., Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978); Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

115. Students for Fair Admissions, 143 S. Ct. at 2141 (2023).

116. Id. at 2155.

117. Id. at 2196 (Thomas, J., concurring).

118. Id. at 2160, 2176.