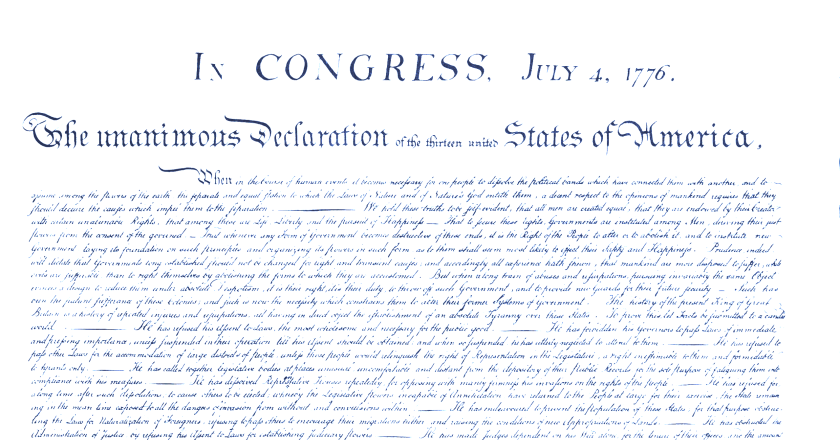

The Declaration of Independence confidently announces that America is now a separate nation from Britain and declares the new nation’s purpose, making it essential to our Founding. To understand and conserve the American nation, we must therefore begin with the Declaration of Independence. America is certainly a home, but more than this, America has been defined by the richness of this document and what it teaches us about our rights and duties as citizens. It contains a clear statement of the principles of politics, lawful government, the divine ground of liberty, the self-governing practices of the colonists, and why they were reclaiming their right to govern themselves in the face of a settled pattern of abuse by the British government.1

The Declaration proclaims that the “thirteen united States of America” now “assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.” The Declaration is a statement about the type of politics and order under which the “United Colonies” would live and why they were rejecting Britain.

The Americans believed there were certain “self-evident” “truths” about the rights of human beings and that a government derives its “just powers from the consent of the governed.” They also believed if they were subjected to “any Form of Government” that was “destructive of these ends”—and the colonists concluded this described the British monarchy—it was “the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

The Declaration announces the political principles worthy of free and virtuous people and concludes that these principles had been violated. The actions of the British King evidenced a settled design of despotic ambition, and the colonists of right and duty determined they would not bow down to it and would instead declare their independence as a people. God—“the laws of nature and of Nature’s God”—warranted this bold action.

Realizing that affixing their names to this document would be tantamount to signing their death warrants if the British prevailed, 56 brave individuals from all 13 colonies signed the Declaration of Independence, stating that “with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” Although tested at times throughout our nation’s history, the spirit of independence and the principles of the Declaration remain true today.

Was such a bold action warranted?

One of the most consequential Supreme Court jurists in American history, Chief Justice John Marshall—whose tenure on the Court lasted from 1801 to 1835, during which he wrote influential opinions on vital constitutional questions in the early republic—reflected upon the Declaration in a letter to Edward Everett, then a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and later President of Harvard:

Our resistance was not made to actual oppression. Americans were not pressed down to the earth by the weight of their chains nor goaded to resistance by actual suffering…. The war was a war of principle against a system hostile to political liberty, from which oppression was to be dreaded, not against actual oppression.[2]

Americans had become well-versed in political liberty for more than 150 years as English colonists in North America, where they had been self-governing in colonial assemblies and law courts and had gained experience with the practices and rights of living under a common law constitution. The phrase “salutary neglect,” coined by Edmund Burke in Parliament in 1775, aptly describes this period of loose regulation of the colonists’ internal affairs and commerce in return for their loyalty to Britain. During this period, the colonists had learned to be self-governing, establishing an array of commercial, professional, civic, and religious relationships and ordering their lives separate from government. The question became unavoidable: Why did the colonists, who had learned they could govern themselves and thrive, need the British government?

The colonists were not anarchists: far from it. Their collective experiences evince a double meaning for the term “self-government” to which Thomas Jefferson of Virginia gave a rational, elegant, and timeless voice in the Declaration. Believing that self-government involved the ability to act in concert with others through voluntary arrangements that stemmed from the natural and moral inclinations of the human person, the colonists chose to be self-governing in a republican political order with limits and checks on government power, thereby ensuring the voluntary arrangements of civil society could occur without undue interference at the hands of an arbitrary sovereign who could reduce them to a servile condition. This crucial separation between state and society forms a bedrock premise of our constitutional order and its insistence on balanced and limited government.3

The Declaration is a practical document written by practical men facing the gravest decision of their lives. All decisions, if they are any good, are the fruit of a marriage between principles and circumstances. Most of the Declaration explains the circumstances that led the Founders to break with Britain.

One sentence in the second paragraph gives us five self-evident truths, building one upon another. The Declaration claims they are “self-evident.” This does not mean they are obvious, but rather that they carry their own evidence within themselves. It is self-evident that triangles are composed of three lines, because to be a triangle is to be composed of three lines; once we know what a triangle is, we know it is made of three lines. The Founders claimed that the five truths upon which they risked their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor were truths of this sort.

The first, upon which all the others rest, is that “all men are created equal.”4 Is this so? It is very easy to think of ways in which we are not equal. Some are strong, others weak. Some are wise, others foolish. Some are good, others wicked. In many times and places, such differences have been politically decisive: People have claimed the right to rule because they were the strongest, the wisest, the most virtuous, or the possessors of some other superlative quality.

But there is one way in which all human beings are equal: We are all equally human beings. This is self-evident: If you and I are both human, then we are equally human. Whatever it is that makes one human can be said with equal truth of us both. As John Adams once explained to his son:

[The Declaration’s first claim] really means little more than that We are all of the same Species: made by the same God: possessed of Minds and Bodies alike in essence: having all the same Reason, Passions, Affections, and appetites. All Men are Men and not Beasts: Men and not Birds: Men and not Fishes. The infant in the Womb is a Man, and not a Lyon…. All these are Men and not Angells: Men and not Vegetables, etc…. The Equality of Nature is a moral Equality only; an Equality of Rights and Obligations; nothing more.[5]

All human beings are equally human, but what is it exactly that we all share from the moment of our creation? The definition of man to which the Founders subscribed, and with it the Western tradition extending back to its beginnings, taught that man is a “rational animal.”

Because man, like the beasts and birds, is a body made of matter, he has certain needs: food to continue his body in being, protection to ward off other animals who would tear him apart, and a partner to help him continue his lineage. Like all animals, he is hardwired with powerful instincts to help him achieve these things. And like all animals, his needs can bring him into conflict with others of his own species whose needs are just as compelling.

Yet man, unlike all other animals, is also rational. One sign of this is his ability to use words to say what things are in themselves and not just emit noises to express his own pleasure, pain, desire, or anger. Man, unlike any other animal, can transcend his own needs and urges. He can see others not as mere objects for his use, but as persons to be known and loved. He can look up toward the summit of all desire, at that greatest good that lies beyond any particular object, and choose to give up the satisfaction of his immediate needs to obtain it.

To live in this way is to do something higher and more beautiful than any other animal can do: Achieve happiness. That word today means something like gladness or contentment, an affair of the feelings. At the time of the Founding, it meant something much greater. To be happy was to thrive as much as it was possible to thrive so things could not go better. Life and liberty are necessary for happiness—we cannot become happy if we are not alive and free to pursue it—but it is more than these things; it fills life and liberty as a child fills a womb.

The Declaration’s breathtaking claim is that all human beings have the right to pursue happiness. No human is merely material for the happiness of another; every single one of us—strong and weak, wise and foolish, virtuous and wicked—exists to become happy and thus has a right to pursue happiness and the life and liberty that are its prerequisites. To trample on these rights is to quarrel with our Creator who destined each for happiness by making him human.

To see what it means to truly thrive as a human being is to see that it must be the aim of our every action and so the aim of our political life. A government faithful to its proper purpose aims at the happiness of each of its citizens—but sometimes governments are not faithful. Rulers have the same needs and instincts all other men have, and these can corrupt their judgment. One great reason governments derive their “just powers” from the “consent of the governed,” as the Declaration claims, is that governments cannot be kept faithful except by the people’s free choice of their rulers. But there is also another reason: Humans have the capacity to discriminate among the bad, the good, and the best, and this capacity is at the heart of politics. Each human being has the right to put this capacity to work by contributing his best practical wisdom to the community’s deliberations.

What follows from these truths is the fifth and crowning claim of the Declaration: that men have the right to throw off their government and found a new one when necessary to protect the rights that a just government exists to serve. That, of course, is what the Founders did in the Declaration and what they made good with their blood and toil in the Revolution that had already broken out. The rest of the document is devoted to showing that the dissolution of their loyalty to the British Crown was, in fact, necessary to preserve their rights because of the circumstances in which they found themselves.

These self-evident truths teach us what the Declaration has to say about man and are crucial to understanding the document. The document, though, must be read as a whole if we are to understand its full nature, purpose, and meaning. While much of the rest of the Declaration is comprised of a list of Grievances, there are “Principles” at stake in those Grievances that are also of tremendous importance.

ENDNOTES:

1. For an authoritative text of the Declaration, see “Declaration of Independence: A Transcription,” National Archives, America’s Founding Documents, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript (accessed October 4, 2024) com%2Fmagazines%2Fdefine-brand-using-hand-made-type%2Fdocview%2F2020448513%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12085 (accessed May 22, 2024).

2. Letter from John Marshall to Edward Everett, August 2, 1826, quoted in R. Kent Newmyer, John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001), p. 1.

3. Hans L. Eicholz, Harmonizing Sentiments: The Declaration of Independence and the Jeffersonian Idea of Self Government (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2001).

4. At the Founding, the word “man” meant “human being.” It also meant a male as distinct from a female, an adult male as distinct from a boy, a servant as distinct from a lord, etc. See Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, Vol. 1 (London: W. Strahan, 1755), https://dn790009.ca.archive.org/0/items/johnsons_dictionary_1755/johnsons_dictionary_1755.pdf (accessed October 4, 2024). The Declaration uses the word in the first sense.

5. John Adams’ Letter to Charles Adams, February 24, 1794.