In November of 1956, Lee Edwards, then a young expat in Paris, heard the news that Soviet tanks had rolled into Budapest. At that moment, he decided to devote his life to fighting the communist menace and supporting freedom fighters however he could. Along the way, he helped activate conservative-minded youth and counseled the conservative movement’s leaders, including Barry Goldwater. Today he wants to make sure that the world doesn’t forget communism’s crimes and that young conservatives know the history of their movement.

Edwards founded the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, which unveiled the Victims of Communism Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 2007. He has written biographies of Barry Goldwater, William F. Buckley, Jr., Ronald Reagan, and Edwin Meese III, as well as numerous histories of the conservative movement. His latest book is an autobiography, Just Right: A Life in Pursuit of Liberty. We sat down with Edwards to talk about his life at the intersections of anti-communism, conservatism, and history.

The Insider: You’ve written a lot on the history of the conservative movement, but you’ve also made some of that history. Is there a particular accomplishment of which you are most proud?

Lee Edwards: I think I’m probably most proud of the memorial to the victims of communism. As you know I’ve always been—since early, early on—an anti-communist. After the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, I determined I’d do whatever I could to help anyone resist communism and further freedom. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, people were beginning to sort of push aside or not remember or want to consider the victims and crimes of communism.

I said we’ve got to do something, and that’s when my wife Anne said: “What we need is a memorial to the victims of communism.”

“Terrific idea,” I said and began working to bring that about. It took us some time. That was January of 1990, and it was some 17 years later that we dedicated the memorial to the more than 100 million victims of communism. We hoped that it would become a place for people to visit, to remember victims, to lay wreaths, to say prayers, to have candlelight vigils—and all of those things have happened. National leaders have come from all over the world to our memorial there on Capitol Hill to lay wreaths. So that is the thing I’m most proud of.

TI: You identify the three pillars of your conservatism as Catholicism, individualism, and anti-communism and then you go on to say that your anti-communism is the root of your conservatism. Could you explain that?

LE: Well I should say that it comes first for me. I’m sure there are others who would say, “I’m a traditional conservative first,” or they would say, “I’m a libertarian first.” I was not well-read in conservative literature in my twenties. I had not read The Conservative Mind. I had not read The Road to Serfdom, but I was already an instinctive anti-communist through not only my own thinking and writing, but through my father. He had been a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, covering many of the famous congressional hearings about communism and anti-communism. Those involved people like Richard Nixon and Joe McCarthy. So, by being an anti-communist, of course I was not only against something—that is to say the tyranny of communism—but I was for something. I was for freedom; I was for the individual. So one could say that OK, to be an anti-communist, you also have to be a libertarian, and also have to be a traditional conservative, but the wedge issue for me was anti-communism.

TI: Middle-aged conservatives tend to think of the modern American conservative movement as starting with Bill Buckley & Co. But when you were coming of age, Buckley had written maybe one book. So I’m curious, who did you read in that period that moved you in a conservative direction?

LE: At that time, I was not doing that much in the way of reading. I was a political activist. So if I thought there was a need to do something, I would get involved either with an organization or be a part of an event, or I would work to make something happen. And it was really more instinctive on my part—opposing the tyranny of communism and trying to promote freedom in the best way that I could.

Probably the one little book that I read that did make a difference for me—and for many, many others—was The Conscience of a Conservative by Barry Goldwater. That was published in 1960, but I was already an anti-communist by that time. But the book did give me a foundation in conservative thought. One of the things that Goldwater talks about in that first chapter of The Conscience a the Conservative is that there are two sides to man: There’s the spiritual side and there’s the economic side. They’re both important, but, he says, the superior side is the spiritual side. That resonated with me because by that time I had become a Catholic.

After the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, I determined I’d do whatever I could to help anyone resist communism and further freedom.

TI: What do you make of the recent revival of interest in socialism?

LE: It is something that is—I won’t say inevitable—but a logical continuation of what liberals/progressives have been trying to do for well over a century, starting way back with Woodrow Wilson, the first progressive. He was followed by TR—Theodore Roosevelt—who was followed by FDR, and then Truman, and then finally reaching its apex—hopefully—with Barack Obama with his version of socialized medicine. You can see that there was this steady progression where the government was becoming bigger and bigger and more and more intrusive. It began getting into all aspects of our lives, not only economic but social and political aspects. Because the counter movements—the counter attacks by conservatives—were not sustained from decade to decade, the liberals have been able to advance on all fronts more successfully than we have been in countering them. The two exceptions were Calvin Coolidge in the 1920s and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

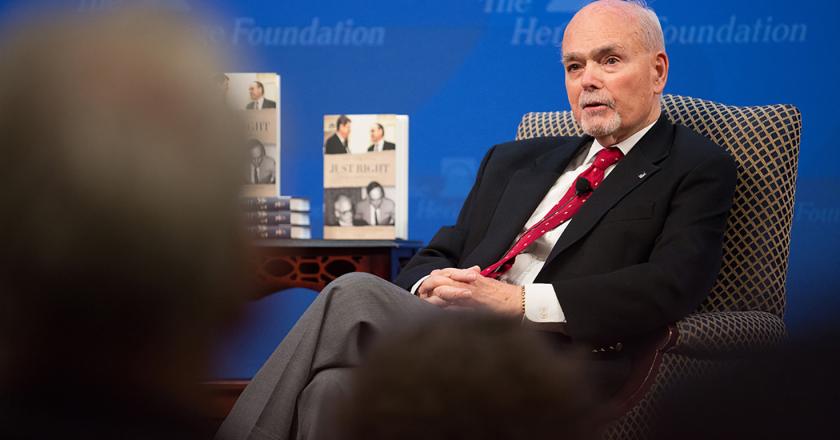

LEE EDWARDS with then-Heritage Foundation president Ed Feulner at the launch of his book, Leading the Way in 2013. (credit: WILLIS BRETZ)

TI: Are we teaching the right lessons about socialism and connecting the dots between socialism and communism?

LE: I don’t think we are, and I think that’s unhappily clear. A recent survey by YouGov showed that a large plurality of millennials would be more comfortable living under socialism than living under capitalism. I think the number was something like 46 percent. That’s disturbing; that’s alarming; that’s dangerous for this country. And so clearly we have not done a good enough job of educating that generation and other generations as well. There’s been this acceptance of socialism as an option. You know the cliché—communism has never failed because it’s never been tried. You hear that argument, and it’s absurd because Communism has been tried in 40 different countries over a century, and it’s failed in every single instance because it’s a god that has failed.

TI: Your organization, the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, has had a long term goal of building a museum. Can you tell us where that effort stands?

LE: Twenty years ago when we got started, we talked about building a museum and then what happened was that reality set in. We realized a museum was a multi-million-dollar project, so we shifted over and made our priority the memorial. We dedicated the memorial in 2007. Since then, we’ve been building the organization. We have a brilliant young executive director, Marion Smith, who’s doing a fantastic job. We just had a great event at Union Station marking out the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution and pointing out over and over again that communism was the god that failed. But now—looking ahead to the next decade or perhaps the next two decades—we’re going to take a serious look at what needs to be done to build a world-class museum of research and remembrance about the victims and the crimes of communism. That’s going to be a very expensive project, but given what we’ve been able to accomplish, and with the people we have led by Marion, I think that it’s an achievable goal over the next decade or so.

TI: Some folks say: Well, anti-communism was fine for Lee Edwards’s generation, but conservatism has to move on in order to remain relevant to younger generations. What do you say to that argument?

LE: I think there’s some validity to that point of view. There’s no question about it that communism, as represented by and led by the Soviet Union, was a clear and present danger. They were out to “bury us” to quote Khrushchev. They were a clear and present danger, no question about that. We met that challenge over the course of some 40 years. Finally, along came the right leader, Ronald Reagan, who in the immortal words of Margaret Thatcher “won the cold war without firing a shot.”

Now, where do we stand today? Is there a similar clear and present danger? I think there is, and I think it is radical Islam. They are out to bury us. In a recent report, The Heritage Foundation counted almost 100 terrorist plots since 9/11. Many of those have been foiled by measures we have taken, including the Patriot Act and its provisions for better cooperation between intelligence agencies. So that to me is a present danger and must be met with a little more vigor and a little more commitment than it has been in the recent past under President Obama.

But, at the same time, we must keep in mind that there are still five communist regimes in the world, and together those countries have more than a billion and a half people. One of those five is China, where there has been some economic liberalization, but it is still totalitarian in politics and human rights. On the list of communist countries, you should also include North Korea, Vietnam, and Cuba. And then you would include a country that is often overlooked, unhappily, and that is Laos. Laos has had a communist regime for 40 straight years now and in many ways life there is almost as difficult as it is in North Korea.

TI: You’ve known most of the giants in the conservative movement. Which ones have inspired you the most?

LE: Well, I think I’ve been inspired by all of them in one way or another, starting with Barry Goldwater, who was my first political hero. His willingness to stand up in 1964 and run for president knowing that he could not win was extraordinary. Here was somebody who stood up for principle under the most extreme pressures and sacrificed himself for the cause. By, as he put it, offering a choice and not an echo, he inspired many of us to get into politics.

I learned from Ronald Reagan. Here was a man just as principled as Barry Goldwater, but a little more pragmatic, a little more willing to bend with the typhoon that comes along, as he put it. He said, I’m a 70 percent kind-of guy; I will take 70 percent of what I want right now if I can come back for the other 30 percent later. He said, I’m not like some who like to go over the cliff with the flags flying and the band playing. So we learned, first of all, principle from Barry Goldwater, and then a principled pragmatism from Ronald Reagan.

And then somebody who we admired for his ability to write, to lecture, to debate, to be a TV host, to be a good friend and mentor was Bill Buckley. As a young conservative, I identified more with Bill Buckley than I did Goldwater or Reagan who were political figures. Because Buckley was more of a communicator, more of a popularizer as I call him, I probably saw or tried to be as much like him as a I possibly could.

We have to pull together, work together, to resist this really eerie, unsettling, acceptance of socialism by too many young Americans. I think the only way to do that is for us to concentrate on what we agree on as conservatives.

TI: On a personal level, from whom did you learn the most?

LE: I had an opportunity to get to know Walter Judd. Dr. Judd was a medical missionary in China in the 1920s and the 1930s and later a congressman for 20 years. Then he was what he called a “missionary for freedom” as a radio broadcaster and lecturer and debater. For 20-some years I knew him and worked with him, and I wrote a biography about him.

He took an anti-communist position at a time when that was not the most popular way to go. He stood up for the alternative of Taiwan as opposed to the alternative of mainland China. He was a man of faith. He was a family man, a father, a good husband. So in so many ways I could see it was possible to have a political career and at the same time be a good Christian, to be a good person, to stick by certain ideas, and to implement them. You didn’t need one or the other, you could be both, so that was inspirational for me.

TI: I know you’ve become a better- read conservative since your bohemian days in Paris. In fact, a couple of years ago, you wrote a book called Reading the Right Books: A Guide for the Intelligent Conservative. In your opinion, what’s the most underappreciated book in the conservative canon—a book that everyone should read but not enough people have heard of?

LE: That’s an interesting way of putting it. I would say the The Roots of American Order by Russell Kirk.

The magisterial book everyone refers to, and properly so, is The Conservative Mind, by Kirk. That is an extraordinary piece of intellectual history. He saw connections that nobody else saw. He could see a connection between Burke and John Adams and T.S. Eliot, and Abraham Lincoln, and Hawthorne, and on and on and on. And what he did with that one book was to establish that there is a conservative tradition in America. Up until that time all the liberals all said there is only one tradition, the liberal tradition. Kirk said no—there is also a conservative—and he proved it with that one book.

And also by Kirk is The Roots of American Order, in which he traces the roots of Western order back 2,500 years. He tells the story of five cities and the ideas they represent. He begins with Jerusalem and the idea of a supreme being. He goes to Athens and the idea of a political philosophy. He goes to Rome and the idea of a senate and of a rule of law. And he then goes to London and the idea of a parliament and the idea of elected representation. Then he winds up in Philadelphia where we find the ideas of separation of powers and checks and balances in a written constitution. Kirk draws this direct line all the way back 2,500 years. It’s a wonderful way of showing that we, in America, rest on Western civilization.

Here was somebody who stood up for principle under the most extreme pressures and sacrificed himself for the cause. By, as he put it, offering a choice and not an echo, Goldwater inspired many of us to get into politics.

TI: Do you see any intellectuals today who are doing a good job of carrying on the work that Kirk, and Buckley, and Richard Weaver, and Frank Meyer started?

LE: Yes, I do. We had one here in this very office. That’s Matthew Spalding, who is now over at Hillsdale College’s Kirby Center. I think Charles Kessler, editor of the Claremont Review, does a marvelous job. I think that Bradley Birzer at Hillsdale is doing outstanding work, as is James Ceaser down at the University of Virginia. There are younger intellectuals and academics who are coming along, including David Azerrad, a brilliant, even mesmerizing, public speaker on the Founding and Progressivism; and Arthur Milikh, equally brilliant about the Founders and Alexis de Tocqueville. Jonah Goldberg is an effective popularizer and very much a Buckley type. And then you have old timers, if you will, who are still turning out good work like George Will, Charles Krauthammer, Victor Davis Hanson. So we have, I think, a very strong lineup of thinkers and interpreters of the conservative canon.

TI: Some people say civility has taken a beating in recent years. Do you recall the political battles of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s being more civil compared to today?

LE: I think that civility was more honored and practiced back when I first got into politics in the ’50s and the ’60s and the ’70s when I was truly active. I think that’s because there were moderates in both parties, if you look at it politically. Also, within the conservative movement, you had a Frank Meyer and a Russell Kirk, who even though they disagreed quite emphatically, were able to come together in the face of a common enemy, which was the Soviet Union externally and liberalism here at home.

But the discourse we have today reflects the divided nature of America. And that division is strongly ideological and philosophical. There is less willingness to make compromises. The liberals are saying: Look, we are getting closer and closer to our goal of an administrative state. We’re not going to compromise now. And the conservatives are saying: Wait. Yeah, we agree we are close to seeing an all-powerful administrative state. We’ve got to stop it. We’ve got to resist every single possible measure that helps you liberals achieve your goals, which we think would be terrible for the country.

TI: You’ve worked both in the media and with the media over the years. Do you see any changes in the way the media operate and the way they cover politics today compared to when you first started off?

LE: Let me give you one example. My father, as I said, was a reporter for the Chicago Tribune for 50 years. He came to Washington in the 1930s and covered it through the 1970s. He covered every president from FDR to Nixon. In the 1950s and 1960s he knew that Jack Kennedy was a serial philanderer and adulterer. He knew it. It was known by the Washington press corps.

And I once said to him: “Well, Dad, you know, the Chicago Tribune is a conservative paper, always for Nixon rather than Kennedy. And yet, you have never written a story about his philandering; neither has anyone else. Why not?”

And he said that there was an unwritten rule among journalists that we would not write about the private doings of a senator or a congressman or even a president so long as it did not affect his public performance. So the fact that Kennedy was going around sleeping all over the place did not seem to effect, materially, what kind of a senator he was or what kind of a president he was.

They would not publish anything about a politician just for the sake of a headline. Today, of course, you’ll get stampeded if you don’t publish the story first before anybody else. The old idea that the public does not have the right to know everything has just been thrown overboard. Now, they say the public has the right to know about a politician’s private conduct, because it goes to the question of character rather than performance. A big difference, and not for the good, I don’t think.

SENATOR BARRY GOLDWATER at the Republican National Convention, ca. 1976. (credit: EVERETT COLLECTION/NEWSCOM)

TI: As you reviewed materials, such as your diary, for your autobiography, did you discover anything that surprised you?

LE: Well, I was surprised because I had not gone back and read that diary for a long time. I never used that diary before in my writing. I never quoted from it. I never consulted it. The 1964 campaign was the only time I ever kept a diary. I thought it would be interesting to record my reactions to events as they happened.

I was surprised to re-read my reaction to Goldwater’s famous quote “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.” I thought I remembered that I had been excited about that line, that I had been jumping up and down about it. In point of fact, I wrote in my diary that this was going to seal our defeat. I would have counseled against using that language. So that was a reversal of what I thought. There were young conservatives at the time, who were jumping up and down about it saying: “This is terrific, we love it.” But I was not one of them, although I thought I was.

TI: What is your advice to the conservative movement today?

LE: Well, I’ve written a big piece about this which I think is going to be in National Affairs soon. I call for a new fusionism. And I really, really think this is what we must strive to achieve. The country is so divided and the conservative movement is so divided—or at least showing serious division. I don’t want to say that it’s an impossibly wide chasm, but it’s getting more and more serious.

So I say that we must bring together all these different straws. We must have a series of debates, a series of discussions—private and public—in which we try to agree on certain basic ideas. We have to pull together, work together, to resist this really eerie, unsettling, acceptance of socialism by too many young Americans. I think the only way to do that is for us to concentrate on what we agree on as conservatives and that would be that we’re opposed to socialism and that we come together. I think that will, in turn, help to encourage the country to come together.

Implicit in that idea though is that there must be the right leadership. I’m not saying that we need someone exactly like Ronald Reagan, but it has to be somebody who consciously works, as Reagan did, to unite people and not divide them.