President Donald Trump is expected to announce July 9 his nominee to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court. In 2016, Trump put together a list of potential Supreme Court picks during his campaign for president and has amended it twice—bringing the current total to 25 highly qualified conservative individuals.

I will be making my choice for Justice of the United States Supreme Court on the first Monday after the July 4th Holiday, July 9th!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 30, 2018

Although the list is brimming with top-notch individuals, there are a few whose names appear to be rising to the top. A look at the judicial records and writings of these men and women reveals insights into their perspectives on a wide array of issues.

Here’s the highlights of their careers and writings you should know about:

- Amy Coney Barrett

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit (Indiana)

Age: 46

Education: Rhodes College; Notre Dame Law School

Clerkships: Laurence Silberman (D.C. Circuit) and Justice Antonin Scalia

(Photo: University of Notre Dame/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

Amy Barrett is a judge on the 7th Circuit, which hears appeals from Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin.

Trump nominated her to that judgeship in the spring of 2017 and she was confirmed last October by a 55-43 vote, with Democratic Sens. Joe Donnelly (Indiana), Tim Kaine (Virginia), and Joe Manchin (West Virginia) voting for her confirmation.

At her confirmation hearing, Senate Democrats chided Barrett for her writings as a law student in 1998 and asked inappropriate questions about her Catholic faith. She responded that “It’s never appropriate for a judge to impose that judge’s personal convictions, whether they derive from faith or anywhere else, on the law.”

Barrett exhibited grace under fire during her contentious confirmation hearing, and she received robust bipartisan support from the legal community, including from Neal Katyal, a prominent liberal who served as President Barack Obama’s acting solicitor general.

Most of her career has been spent in academia, but following two clerkships, Barrett worked in private practice, where she was part of the team that represented George W. Bush in Bush v. Gore. She briefly taught at George Washington University and the University of Virginia before joining the Notre Dame Law faculty in 2002. She also served on the Advisory Committee on the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure for six years.

Barrett is a prolific writer, having published in leading law reviews across the country on topics including originalism, federal court jurisdiction, and the supervisory power of the Supreme Court. In an article discussing stare decisis and precedent, she explained that “public response to controversial cases like Roe [v. Wade] reflects public rejection of the proposition that stare decisis can declare a permanent victor in a divisive constitutional struggle rather than desire that precedent remain forever unchanging.”

In another article, she examined the conflict between the law and a Catholic judge’s religious views on capital punishment. She and her co-author concluded, “Judges cannot—nor should they try to—align our legal system with the Church’s moral teaching whenever the two diverge. They should, however, conform their own behavior to the Church’s standard.”

Since joining the bench, she has written eight published opinions, including cases dealing with products liability, enforcing arbitration agreements, federal pre-emption, the sentencing guidelines, a disability benefits claim, and debt collection. She has written one dissenting opinion, Schmidt v. Foster, involving application of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel in nonadversarial proceedings. She explained:

[T]he Sixth Amendment was designed ‘to minimize imbalance in the adversary system that otherwise resulted with the creation of a professional prosecuting official.’ …While the Amendment’s protection is not limited to the formal trial, ‘[t]he Court consistently has applied a historical interpretation of the guarantee, and has expanded the constitutional right to counsel only when new contexts appear presenting the same dangers that gave birth initially to the right itself.’ … The ‘new contexts’ to which the Court has extended the right invariably involve a confrontation between the defendant and his adversary, be it a prosecutor, the police, or one of their agents.

Barrett’s limited judicial opinions and academic writings indicate a commitment to originalism and textualism, much like her former boss, Scalia.

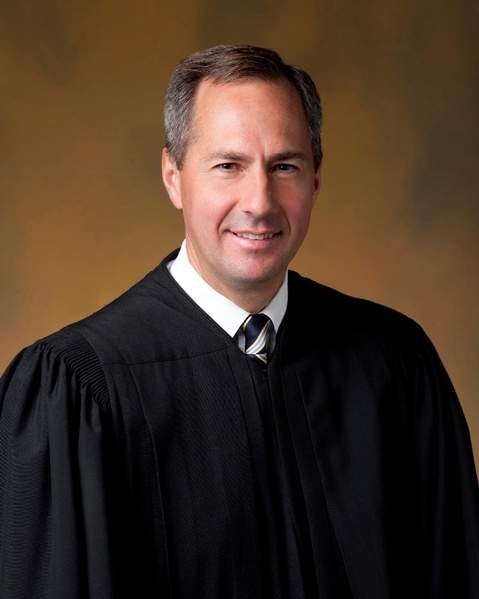

- Tom Hardiman

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit (Pennsylvania)

Age: 53

Education: University of Notre Dame; Georgetown University Law Center

Clerkships: None

(Photo: U.S. Court of Appeals/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

Tom Hardiman is a judge on the 3rd Circuit, which has jurisdiction over Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Before becoming a judge, Hardiman worked in private law practice for several years at prestigious law firms in Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C. While in private practice, he represented (on a pro bono basis) and successfully defended Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, against a lawsuit filed by a group of atheists who objected to the county’s display of a Ten Commandments plaque on the side of the county courthouse.

In 2003, President George W. Bush nominated Hardiman to a seat on the U.S. District Court in Pittsburgh, and in September 2006, Bush nominated Hardiman to the 3rd Circuit. He was confirmed by the Democratic-controlled Senate 95-0—a rare feat for nominees during Bush’s presidency.

Hardiman was widely reported to be the “runner up” to Neil Gorsuch for Trump’s first Supreme Court pick. This is perhaps due in part to Hardiman’s close relationship with the president’s sister, Judge Maryanne Trump Barry, who also serves on the 3rd Circuit.

Hardiman has heard hundreds of appeals and produced noteworthy opinions dealing with the Second Amendment, prisoner’s rights, and religious freedom. In 2013 in Drake v. Filko, Hardiman dissented from the court’s ruling upholding a New Jersey law requiring those seeking a permit to carry a handgun to demonstrate a “justifiable need.” Hardiman argued that under the Supreme Court’s 2008 opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller, the Second Amendment extends beyond the home and encompasses an inherent right to self-defense.

Moreover, in 2016, in Binderup v. Attorney General, in which the court held that two people convicted of nonviolent felonies should not have been denied their Second Amendment rights to bear arms, Hardiman concurred in the judgment, writing that “a law that burdens persons, arms, or conduct protected by the Second Amendment and that does so with the effect that the core of the right is eviscerated is unconstitutional.”

In 2010, Hardiman wrote an opinion in Florence v. Board of Chosen Freeholders upholding the constitutionality of a Pennsylvania jail’s policy of strip searching all detainees regardless of how minor an offense they were arrested for, which was affirmed by the Supreme Court. In 2016, however, Hardiman ruled in favor of a challenge filed by a prisoner in Robinson v. Superintendent.

In 2009, in Busch v. Marple Newtown School District, Hardiman wrote a dissenting opinion arguing that an Evangelical Christian mother should not have been denied the opportunity to read from the Bible during a show-and-tell session at her child’s kindergarten.

In 2010, in Kelly v. Borough of Carlisle, Hardiman wrote the majority opinion in favor of a police officer holding that he was immune from a civil suit that had been filed against him because at the time of the conduct in question, there was no clearly established First Amendment right to videotape police officers during traffic stops.

In addition to a solid record of judicial service, Hardiman also has a compelling personal story—he was the first in his family to attend college and he drove a taxi to support himself during college and law school.

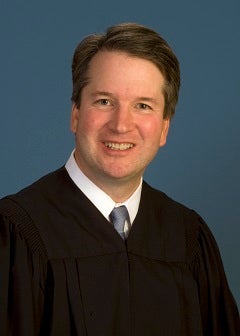

- Brett Kavanaugh

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

Age: 53

Education: Yale University; Yale Law School

Clerkships: Walter Stapleton (3rd Circuit); Alex Kozinski (9th Circuit); Justice Anthony Kennedy

(Photo: U.S. Court of Appeals/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

Brett Kavanaugh has served on the powerful D.C. Circuit—often regarded as a stepping-stone to the Supreme Court—for 12 years.

Before joining the bench, he worked as a senior associate counsel and assistant to President George W. Bush. He also worked for independent counsel Ken Starr and was the principal author of the Starr report to Congress on the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Bush nominated him to the D.C. Circuit in 2003, but he was not confirmed until 2006, by a vote of 57-36.

Kavanaugh has written extensively about the separation of power and statutory interpretation, and he co-authored a book on judicial precedent (with Bryan Garner and 11 appeals court judges, including then-Judge Neil Gorsuch).

Drawing from his experience working for Bush, Kavanaugh argued in an article that Congress should consider enacting a law that would protect a sitting president from criminal investigation, indictment, or prosecution while in office. He explained, “The indictment and trial of a sitting president … would cripple the federal government, rendering it unable to function with credibility in either the international or domestic arenas. Such an outcome would ill serve the public interest, especially in times of financial or national security crisis.”

He delivered the 2017 Joseph Story Distinguished Lecture at The Heritage Foundation—joining the ranks of Justice Clarence Thomas and many other renowned federal judges. He spoke eloquently about the judiciary’s essential role in maintaining the separation of powers.

On the bench, Kavanaugh has written scores of opinions, including PHH Corp. v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2016), finding the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s structure is unconstitutional (later reversed by the full D.C. Circuit).

He dissented from his court’s ruling that the Environmental Protection Agency could disregard cost-benefit analysis when considering a proposed rule in Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA (2012). The Supreme Court later reversed that decision, citing Kavanaugh’s dissenting opinion.

In Loving v. IRS (2013), Kavanaugh ruled that the IRS exceeded its statutory authority when it attempted to regulate tax preparers. And in al-Bahlul v. U.S. (2015), Kavanaugh joined the per curiam (unsigned) en banc opinion, affirming Ali Hamza al-Bahlul’s conviction by a military commission for conspiracy to commit war crimes.

Before the Supreme Court’s landmark Citizens United v. FEC decision, Kavanaugh ruled in Emily’s List v. FEC (2009) that the commission’s regulation restricting how nonprofits raise and spend money violates the First Amendment.

He wrote the opinion In Re Aiken County (2013), dealing with the Obama administration disregarding federal law in the context of a dispute over nuclear waste storage at Yucca Mountain in Nevada.

He upset some conservatives with a dissenting opinion in Seven-Sky v. Holder (2011), in which he said the federal courts lacked jurisdiction to hear the constitutional challenge to Obamacare. He explained, “There is a natural and understandable inclination to decide these weighty and historic constitutional questions. But in my respectful judgment, deciding the constitutional issues in this case at this time would contravene an important and long-standing federal statute, the Anti-Injunction Act, which carefully limits the jurisdiction of federal courts over tax-related matters.”

Last fall, he dissented from the D.C. Circuit’s ruling in Garza v. Hargan that cleared the path for an illegal alien minor to immediately obtain an abortion while in federal custody.

Kavanaugh has distinguished himself as a thoughtful jurist who is not afraid to stake out bold positions on complex issues. In fact, we included him on The Heritage Foundation’s list of potential Supreme Court nominees.

- Raymond Kethledge

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit (Michigan)

Age: 51

Education: University of Michigan; University of Michigan Law School

Clerkships: Ralph Guy, Jr. (6th Circuit) and Justice Anthony Kennedy

(Photo: Freedom’s Defense Fund/ZUMA Press/Newscom)

Raymond Kethledge serves as a judge on the 6th Circuit, which hears appeals from Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee.

In addition to serving as counsel to then-Sen. Spencer Abraham, R-Mich., on the Judiciary Committee, he spent several years in private practice and as in-house counsel at the Ford Motor Co., during which he devoted a significant amount of time to doing pro bono work and supporting charitable causes,

President George W. Bush nominated him to the 6th Circuit in 2006. His confirmation was delayed for nearly two years because both of Michigan’s Democratic senators pressed Bush to nominate Helene White (originally a Clinton nominee) to fill a second vacancy on that court. After Bush agreed to nominate White, Kethledge was confirmed by a voice vote without opposition.

Kethledge co-authored the book “Lead Yourself First: Inspiring Leadership Through Solitude,” profiling leaders such as Pope John Paul II, Martin Luther King Jr., and Defense Secretary James Mattis. He wrote:

Some leadership decisions bring consequences that are more than professional. Frequently those consequences take the form of moral criticism, where opponents criticize not only the decision itself, but the person who would dare make it … [saying] that she is selfish, irresponsible, or callous. The very point of these criticisms is to enforce conformity, and thus to prevent the leader from making these decisions in the first place. Moral courage is what enables a leader to make them nonetheless. It requires not only clarity, but conviction.

He also wrote an article about ambiguity and agency deference for the Vanderbilt Law Review, in which he criticized the Chevron doctrine that shows considerable deference to legislative agencies in interpreting ambiguous states, rejected reliance on legislative history in interpreting statutes, and stated that he believes a judge’s role in statutory and constitutional cases is to apply “the meaning that the citizens bound by the law would have ascribed to it at the time it was approved.”

In his opinions, Kethledge has a colorful writing style, and he has touched on a number of hot-button political issues. In 2016, he wrote the opinion in United States v. NorCal Tea Party Patriots, a case involving a class action brought by various tea party organizations seeking information from the IRS regarding whether they had been targeted for denial of tax-exempt status due to their political beliefs.

Kethledge rejected the IRS’ argument and rebuked the government’s attorneys for failing to uphold the Justice Department’s “long and storied tradition of defending the nation’s interests and enforcing its laws—all of them, not just selective ones—in a manner worthy of the Department’s name.”

In 2014 in EEOC v. Kaplan Higher Education Corp., the commission sued Kaplan, a for-profit education company, for running credit checks on prospective course enrollees. The EEOC claimed this had a “disparate impact” on African-Americans and had no business justification.

In an opinion dubbed by The Wall Street Journal editorial board as the “Opinion of the Year,” Kethledge rejected the EEOC’s argument, noting that the credit check complained of was precisely “the same type of background check that the EEOC itself uses.” Kethledge explained that the credit check process was “racially blind” and that Kaplan had good reason to conduct credit checks on “applicants for positions that provide access to students’ financial-loan information” because past employees had “stolen payments” and “engaged in self-dealing.”

In 2013 in Bailey v. Callaghan, Kethledge wrote the majority opinion upholding Michigan’s law prohibiting school districts from collecting teachers’ union dues through a payroll deduction.

Also in 2013 in Bennett v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., Kethledge wrote an opinion holding State Farm liable for the injuries suffered by a pedestrian when she was hit and thrown onto the hood of a car whose driver was insured by State Farm. State Farm had argued that the suit against it was “ridiculous,” because its policy only covered “occupants” of a vehicle.

In a classic textualist analysis, Kethledge acknowledged that in ordinary parlance the term “occupant” would not include someone temporarily on the hood of a car. He added, however, that the specific policy in question defined “occupying” as “in, on, entering or alighting from,” and that the plain meaning of this phrase therefore covered parties whose injuries caused them to be “on” a car.

Pithily rejecting to State Farm’s “ridiculousness” argument, Kethledge noted that “[t]here are good reasons not to call an opponent’s argument ‘ridiculous,’ … includ[ing] civility …. [b]ut here the biggest reason is more simple: the argument that State Farm derided as ridiculous is instead correct.”

In 2016 in Tyler v. Hillsdale County Sheriff’s Department, Kethledge joined a concurring opinion in which the court held that a federal statute that permanently stripped the Second Amendment rights of an individual who had been involuntarily committed 28 years beforehand was unconstitutional.

In 2013 in United States v. Hughes, a sentencing case, Kethledge wrote that “statutes are not artistic palettes, from which the court can daub different colors until it obtains a desired effect. Statutes are instead law, which are bounded in a meaningful sense by the words that Congress chose in enacting them.”

Kethledge’s record shows a commitment to textualism and even in the dullest of cases, his opinions are delightful to read.

- Joan Larsen

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit (Michigan)

Age: 49

Education: University of Northern Iowa; Northwestern Law School

Clerkships: David Sentelle (D.C. Circuit) and Justice Antonin Scalia

In this 2016 photo, Joan Larsen, justice of the Michigan Supreme Court and a former clerk for Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, speaks at a memorial for Scalia at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Susan Walsh/UPI/Newscom)

Joan Larsen is a judge on the 6th Circuit. Trump nominated her in May 2017 and she was initially blocked by Michigan’s Democratic Sens. Debbie Stabenow and Gary Peters. Eventually, her nomination advanced in the Senate and she was confirmed by a 60-38 vote, with the two Michigan Democrats and Democratic Sens. Tom Carper (Delaware), Joe Donnelly (Indiana), Heidi Heitkamp (North Dakota), Joe Manchin (West Virginia), Bill Nelson (Florida), and Mark Warner (Virginia) voting in her favor.

Earlier in her career, Larsen worked in private practice in Washington. She also served as deputy assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel when the so-called “Torture Memos” were written. She did not contribute to those memos but co-authored a still-classified memo on detainees’ ability to challenge their detentions.

She spent the next 12 years as a lecturer at the University of Michigan School of Law, where she taught constitutional law, criminal procedure, and presidential power. Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican, appointed her to the Michigan Supreme Court in 2015 after a justice stepped down. Larsen ran for election the next year to finish the remainder of her predecessor’s term, and she won 58 percent of the vote.

She wrote a 2004 law review article in which she criticized the use of foreign and international law in interpreting our Constitution. She co-authored a 1994 law review article discussing how the unwritten traditions of the Constitution’s Incompatibility Clause, which limits members of Congress’ and senators’ ability to simultaneously serve in the executive branch, has strengthened the executive. She wrote a 2010 law review article arguing that modern juries are inconsistent under the original meaning of the Constitution.

Her judicial record is thin compared to the majority of the other potential nominees. While on the Michigan Supreme Court, she wrote six opinions, including In Re Hicks (2017), vacating a district court’s order terminating the parental rights of an intellectually disabled woman. She also wrote the majority in Yono v. Department of Transportation (2016), finding the state of Michigan was immune from suit under a state tort law for an injury that occurred in a parallel parking lane on a highway.

Since joining the federal bench, Larsen has written 11 unpublished opinions, which are opinions that do not appear in the Federal Reporter and typically have no precedential value. These include cases dealing with the sentencing guidelines, removal of aliens by the Board of Immigration Appeals, a couple cases involving the termination of disability benefits, and a landlord-tenant dispute.

Her record as a judge is limited but she has demonstrated a commitment to conservative principles. She’s also shown some of her former boss’ sass: When asked “what it was like to be a woman clerking for Justice Scalia,” she has often quipped: “[m]uch like being a man clerking for him.”

- Amul Thapar

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit (Michigan)

Age: 49

Education: Boston College; University of California, Berkeley Law

Clerkships: Arthur Spiegel (Southern District of Ohio); Nathaniel Jones (6th Circuit)

Amul Thapar was Trump’s second judicial nominee following the appointment of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. Last May, the Senate confirmed Thapar to the 6th Circuit on party lines, by a vote of 52-44 (four Democrats abstained from voting).

Before ascending to the appeals court, he spent nearly a decade as a trial judge on the Eastern District of Kentucky. President George W. Bush nominated Thapar to that judgeship in May 2007, and he was confirmed by a voice vote in December 2007, making him the first South Asian-American federal judge and one of the youngest in the entire federal judiciary. He also volunteered to hear immigration cases during a judicial emergency in the Southern District of Texas.

Before joining the federal court, he served as an assistant U.S. attorney in the District of Columbia and in the Southern District of Ohio and later as the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Kentucky. He also worked in private practice in Washington, D.C., and Cincinnati, Ohio, and served as general counsel for Equalfooting.com, a business-to-business online marketplace.

In a recent Michigan Law Review article, Thapar and attorney Benjamin Beaton reviewed former 7th Circuit Judge Richard Posner’s new book in which Posner recommends abandoning a formalist approach in which judges rely on historical meaning, established interpretive tools, and precedent in favor of a more consequentialist, more overtly outcome-driven approach.

Thapar offers a robust defense of textualism, arguing that Posner’s approach would prove unworkable and unpredictable and would turn judges into policymakers, thereby violating separation of powers. He concluded the article:

Because judges are human, formalism is in a sense aspirational. As Justice Scalia admitted, ‘the main danger in judicial interpretation of the Constitution—or, for that matter, in judicial interpretation of any law—is that the judges will mistake their own predilections for the law. Avoiding this error is the hardest part of being a conscientious judge; perhaps no conscientious judge ever succeeds entirely.’ But this is no basis for rejecting a formal approach to interpreting legal texts; it only heightens the need to incorporate limits, rather than license, into the judicial system. That textualism will sometimes fail to constrain judges is no reason to surrender to other interpretive approaches that, by their very design, impose fewer and less effective constraints.

Although he has only been an appeals court judge for little over a year, he wrote 36 appeals court opinions when he sat on the 6th and 11th circuits by designation, and he’s written 10 published opinions since his confirmation last year. As a district court judge, Thapar published 631 orders—only 11 of which were reversed on appeal.

Thapar appears to be a committed textualist. In Freeland v. Liberty Mut. Fire Ins. Co. (2011), Thapar remanded a diversity case back to state court because it was “exactly one penny short of the jurisdictional minimum of the federal courts.” While admitting that this result was “painfully inefficient,” he said that “[t]he words [amount] ‘in controversy’ have to mean something” and that the statute’s text left no other choice.

In Duncan v. Muzyn (2018), a case dealing with how much notice the Tennessee Valley Authority’s pension board must give members before voting to approve an amendment to the plan, the board argued that it should be granted deference because its rules are ambiguous. In declining to defer to the board’s interpretation, Thapar wrote:

Simply calling something ambiguous does not make it so. Indeed, determining the point at which ‘ambiguousness constitutes an ambiguity’ is no easy task. Contract language is not ambiguous merely because the parties interpret it differently … Rather, where, as here, one interpretation far better accounts for the language at issue, the language is not ambiguous.

In terms of the First Amendment, Thapar joined the majority opinion (along with Kethledge) in Bormuth v. Jackson holding that a county board’s practice of opening public meetings with a prayer by a county commissioner did not violate the Establishment Clause.

And in one of his more controversial decisions on the district court, Thapar ruled in Winter v. Wolnitzek (2016) that a number of Kentucky’s judicial conduct rules prohibiting judges from making campaign contributions to others, campaigning as a member of a political organization, and making speeches for or against political organizations were unconstitutional.

Thapar explained:

There is simply no difference between ‘saying’ that one supports an organization by using words and ‘saying’ that one supports an organization by donating money. Put more plainly, if a candidate can speak the words ‘I support the Democratic Party,’ then he must likewise be allowed to put his money where his mouth is.

The 6th Circuit praised Thapar’s “thorough and thoughtful opinion,” while overruling the portion of his opinion regarding campaign contributions.

Although he spent much of his career as a federal prosecutor, as a district court judge, Thapar has on occasion ruled in favor of criminal defendants. For example, in U.S. v. Sydnor (2017), Thapar excluded inculpatory statements made by the accused that were obtained before he was given his Miranda warnings, and in U.S. v. Lee (2012), Thapar suppressed evidence that was obtained after the police tracked the defendant using a GPS tracking device without first obtaining a warrant.

And as an appellate judge, he wrote an opinion in United States v. Perkins (2018), affirming the trial judge’s motion to suppress evidence police obtained in a drug investigation based on an anticipatory warrant where the triggering event never happened. He wrote that the government’s interpretation (which made the triggering event irrelevant to the warrant) “lacks common sense,” “runs afoul of the Fourth Amendment,” and is not simply a “hypertechnicality” the court should overlook.

Of the judges Trump has appointed so far, Thapar has the most extensive record of judicial service, covering a range of issues from the criminal justice system to the First Amendment. He also has close ties to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and rumor has it Trump interviewed Thapar for the Supreme Court seat that ultimately went to Gorsuch.

Last week, Trump told reporters, “Outside of war and peace … the most important decision you make is the selection of a Supreme Court judge.” He’s absolutely right to take this decision seriously.

Judicial appointments are one of the longest-lasting legacies for a president—with judges serving decades beyond that president’s four- or eight-year term. And the selection of Kennedy’s successor could affect the balance of the court for years to come.

The 25 “short listers”—including those profiled above—all would be great additions to the Supreme Court, and we’ll know in the next week whom Trump will pick.

This piece originally appeared in the Daily Signal