The farm bill is up for reauthorization this year. But despite its name, the vast majority of spending in the farm bill goes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, previously known simply as food stamps.

Given the size of SNAP, the farm bill is a significant opportunity to improve the nation’s welfare system. One of the most important reforms to food stamps would be to expand the program’s minimal work requirement, to promote upward mobility for more Americans.

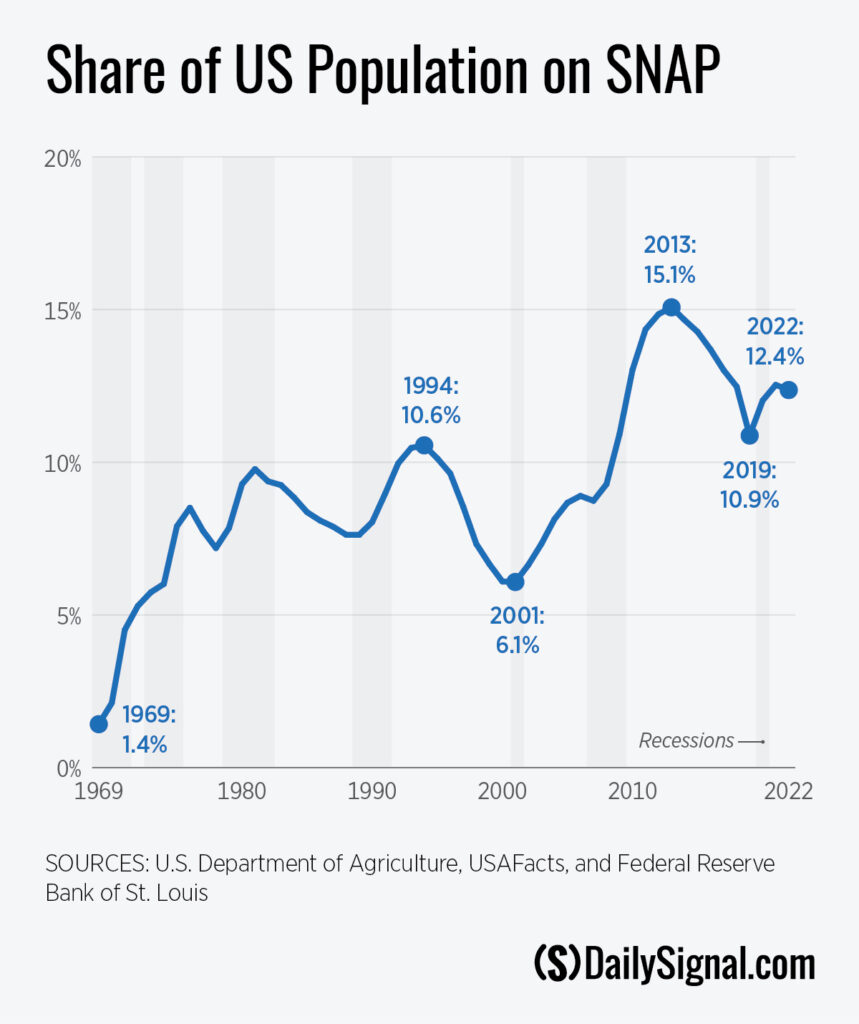

SNAP is one of the largest of the federal government’s numerous means-tested welfare programs, with 42 million Americans (13% of the population) receiving benefits as of May. The food stamps program has grown substantially throughout the years, typically surging during a recession but then rarely returning to pre-recession levels.

Most recently, program participation grew during the COVID-19 pandemic, and benefit levels surged. Spending on food stamps will remain far above pre-pandemic levels for at least the next decade due to benefit increases made by the Biden administration.

Those who paid close attention to the debt ceiling debate earlier this year will recall that Republicans won a small expansion in the work requirement for SNAP in the final bill. Able-bodied adults without dependents (so-called ABAWDs) receiving food stamp benefits now are subject to a work requirement until age 55, rather than 50.

The new law also limits the number of ABAWDs for whom states may waive the work requirement without cause and prohibits states from rolling over unused waivers from year to year. Small steps, but in the right direction.

However, the debt ceiling agreement also added new exemptions from SNAP work requirements for some groups: veterans, homeless individuals, and former adult foster children younger than 25.

Because of these exemptions, the Congressional Budget Office projects the number of Americans eligible for SNAP will increase over the next decade at an additional cost of $2.1 billion. Although some Republicans argue that CBO’s calculations are incorrect—claiming that the budget agency double-counted some newly exempt individuals in its analysis—any way you look at it, the changes made in the debt ceiling agreement were small.

In other words, plenty of work remains to be done to improve SNAP. Congressional Republicans got the ball rolling by broaching the topic of work requirements during the debt ceiling debate. They should keep up the momentum during the farm bill discussions.

Work requirements promote upward mobility, which should be the goal of any good welfare program. Work requirements also support marriage, a vital protector against poverty.

What’s more, work is associated with greater mental health and with an increased sense of purpose; working helps human beings build valuable social capital, an important resource for human thriving.

Unfortunately, many Americans have become disconnected from the labor force, particularly those with less than a college education, and SNAP and the broader welfare system are complicit in this problem.

As a blueprint for work reforms, policymakers can build on previous efforts. The proposed amendment to the 2018 farm bill by Rep. Tom McClintock, R-Calif., would have created a significant work requirement for able-bodied adults (excluding parents of young children).

Also, several members of Congress recently introduced legislation to reform work requirements for the food stamp program, including Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, Rep. Dusty Johnson, R-S.D., and Rep. Eric Burlison, R-Mo.

Besides work requirements, some of their proposals address other much needed reforms. For example, rolling back large spending increases the Biden administration implemented through executive overreach, removing SNAP’s broad-based categorical eligibility loophole that allows those with large amounts of savings to qualify for SNAP, reducing fraud, increasing states’ financial role, and reducing the program’s marriage penalties.

Ultimately, policymakers should view SNAP reforms as part of a broader plan to reform the nation’s vast welfare system. This system consists of nearly 90 programs that cost more than $1 trillion annually.

Most welfare programs undermine work and penalize marriage, two of the greatest protectors against poverty. Consolidating some of these programs and reforming them to promote work, along with reducing marriage penalties, should be the larger aims of reforming the welfare system.

Congress should not overlook the farm bill as an opportunity to move the welfare system toward these important goals.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Signal